The social-cognitive perspective on personality is a theory that emphasizes cognitive processes, such as thinking and judging, in the development of personality. These cognitive processes contribute to learned behaviors that are central to one's personality. By observing an admired role model, an individual may choose to adopt and emphasize particular traits and behaviors.

Mischel's Cognitive-Affective Model

Walter Mischel (1930–present) is a personality researcher whose work has helped to shape the social-cognitive theory of personality. He ignited a controversy in the field of personality research in 1968 when he deliberately criticized trait theories and proposed that an individual's behavior in regard to a trait is not always consistent. Prior to his research, trait theories argued that an individual's behavior is mostly dependent on traits like conscientiousness and sociability, and these traits are expected to be consistent across different situations. Mischel's experiments suggested that an individual's behavior is not simply the result of his or her traits, but fundamentally dependent on situational cues—the needs of a given situation. Mischel's ideas led him to develop the cognitive-affective model of personality.

Cognitive-Affective Model of Personality

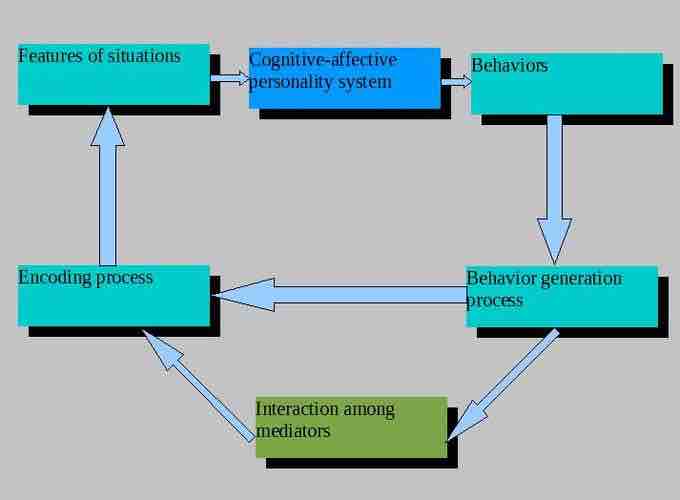

Mischel's research in personality led him to develop the cognitive-affective model, which argues that an individual's behavior, rather than simply being a result of traits, is fundamentally dependent on situational cues—the needs of a given situation. As shown in this diagram, features of situations, behaviors, behavior generation processes, and encoding processes are all interconnected.

The Person–Situation Debate

The conflict of ideas between trait theories and Mischel's cognitive-affective model became known as the person–situation debate, or "trait vs. state." If someone is considered "nice," are they nice in every situation? Is the trait more important in predicting behavior, or the situation? Some traits, like intellect, are stable across situations; however, people may change other aspects of their personality from situation to situation. Although his early research focused mostly on the importance of situation, this controversy was stimulated specifically by Mischel's later research showing that both trait and situation are important in predicting behavior. This argument contradicted the fundamental tenet of trait theory that only internal traits, not external situations, should be taken into account.

Mischel made the case that the field of personality research was searching for consistency in the wrong places. Rather than treating situational factors as "noise" that caused errors of measurement in personality, Mischel encouraged researchers to incorporate situational findings into their experiments and look for the consistencies that characterize an individual in a variety of contexts. He found that although behavior was inconsistent across different situations, it was much more consistent within situations—so that a person’s behavior in one situation would likely be repeated in a similar one.

Personality Signatures

Mischel suggested that consistency would be found in distinctive but stable patterns of "if-then" situation-behavior relations that form personality signatures. In other words, if x situation occurs, then y behavior might result. Rather than defining people merely by their traits ("he is an irritable person"), he argued that personality research should factor in the importance of the context ("he is irritable when talked down to"). In this way, Mischel emphasized the importance of physical, social, and environmental forces in shaping behavior.

The theory of personality signatures was supported in a large observational study of social behavior across multiple repeated situations over time (Mischel & Shoda, 1995). These findings contradicted the classic trait-theory assumption that individuals who shared a specific trait would behave in a similar manner. In Mischel's study, individuals who were similar in average levels of behavior, such as aggression, differed predictably and dramatically in their aggressive behavior depending on the type of situation they were in. Their behaviors supported the "if-then" behavioral signatures proposed by Mischel. This work has given researchers a new way to conceptualize and assess both stability and variability in behavior that is produced by the underlying personality system.

Self-Regulation

One of Mischel’s most notable contributions to personality psychology is his work on self-regulation. Self-regulation refers to the ability to set and work toward goals; it is often described as willpower and often relates to the ability to delay gratification. Delayed gratification is the concept of denying oneself a reward in the present to get a better reward in the future.

Mischel's now-famous Stanford marshmallow experiment examined the processes and mental mechanisms that enable a young child to forego immediate gratification and wait for a better, but delayed, reward. Preschoolers were presented with a marshmallow (or other small snack) and offered the choice of eating the snack immediately or getting two snacks if they waited 15 minutes to eat it (while the researcher left the room). What Mischel found was that young children differ in their degree of self-control. Mischel and his colleagues continued to follow this group of preschoolers through high school, and they found that children who had more self-control in preschool (the ones who waited for the bigger reward) were more successful in high school. They had higher SAT scores and more positive peer relationships, and were less likely to have substance abuse issues; as adults, they also had more stable relationships (Mischel, Shoda, & Rodriguez, 1989; Mischel et al., 2010). On the other hand, those children who had poor self-control in preschool (the ones who grabbed the one marshmallow) were not as successful in high school and were found to have academic and behavioral problems.

Today, the "trait vs. state" debate is mostly resolved, as most psychologists consider both the situation and personal factors in understanding behavior. For Mischel (1993), people are situation processors: the children in the marshmallow test each processed, or interpreted, the reward structure of that situation in their own way. Mischel’s approach to personality stresses the importance of both the situation and the way the person perceives the situation; instead of behavior being determined by the situation, people use cognitive processes to interpret the situation and then behave in accordance with that interpretation.