Background

Congress is split into two chambers: the House of Representatives and the Senate. Congress writes national legislation by dividing work into separate committees which specialize in different areas. Some members of Congress are elected by their peers to be officers of these committees. Ancillary organizations such as the Government Accountability Office and the Library of Congress provide Congress with information, and members of Congress have staff and offices to assist them. Additionally, a vast industry of lobbyists helps members write legislation on behalf of diverse corporate and labor interests.

Senate Apportionment and Representation

The Constitution stipulates that no constitutional amendment may be created to deprive a state of its equal suffrage in the Senate without that state's consent. The District of Columbia and all other territories (including territories, protectorates, etc.) are not entitled to representation in either House of the Congress. The District of Columbia elects two shadow senators, but they are officials of the D.C. city government and not members of the U.S. Senate. The United States has had 50 states since 1959, so the Senate has had 100 senators since 1959.

The disparity between the most and least populous states has grown since the Connecticut Compromise, which granted each state two members of the Senate and at least one member of the House of Representatives, for a total minimum of three presidential Electors, regardless of population. This means some citizens are effectively an order of magnitude better represented in the Senate than those in other states. For example, in 1787, Virginia had roughly ten times the population of Rhode Island. Today, California has roughly seventy times the population of Wyoming, based on the 1790 and 2000 censuses. Seats in the House of Representatives are approximately proportionate to the population of each state, reducing the disparity of representation.

House of Representatives Apportionment and Representation

Under Article I, Section 2 of the Constitution, seats in the House of Representatives are apportioned among the states by population, as determined by the census conducted every ten years. Each state, however, is entitled to at least one Representative.

The only constitutional rule relating to the size of the House reads, "The Number of Representatives shall not exceed one for every thirty Thousand. Congress regularly increased the size of the House to account for population growth until it fixed the number of voting House members at 435 in 1911. The number was temporarily increased to 437 in 1959 upon the admission of Alaska and Hawaii, seating one representative from each of those states without changing existing apportionment, and returned to 435 four years later, after the reapportionment consequent to the 1960 census.

The Constitution does not provide for the representation of the District of Columbia or territories. The District of Columbia and the territories of American Samoa, Guam, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands are represented by one non-voting delegate each. Puerto Rico elects a Resident Commissioner, but other than having a four-year term, the Resident Commissioner's role is identical to the delegates from the other territories. The five Delegates and Resident Commissioner may participate in debates. Prior to 2011, they were also allowed to vote in committees and the Committee of the Whole when their votes would not be decisive.

States that are entitled to more than one Representative are divided into single-member districts. This has been a federal statutory requirement since 1967. Prior to that law, general ticket representation was used by some states. Typically, states redraw these district lines after each census, though they may do so at other times. Each state determines its own district boundaries, either through legislation or through non-partisan panels. Disproportion in representatives is unconstitutional and districts must be approximately equal in. The Voting Rights Act prohibits states from gerrymandering districts .

Gerrymandering Comparison

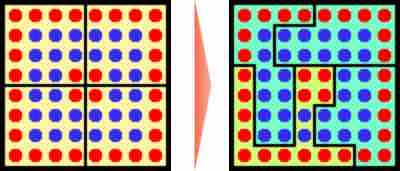

In this example, the more even distribution is on the left and the gerrymandered distribution is on the right.

Comparison to the Senate

As a check on the popularly elected House, the Senate has several distinct powers. For example, the "advice and consent" powers are a sole Senate privilege. The House, however, can initiate spending bills and has exclusive authority to impeach officials and choose the President in an Electoral College deadlock. The Senate and House are further differentiated by term lengths and the number of districts represented. Unlike the Senate, the House is more hierarchically organized, with leadership roles such as the Whips and the Minority and Majority leaders playing a bigger part. Moreover, the procedure of the House depends not only on the rules, but also on a variety of customs, precedents, and traditions. In many cases, the House waives some of its stricter rules (including time limits on debates) by unanimous consent. With longer terms, fewer members and (in all but seven delegations) larger constituencies, senators may receive greater prestige. The Senate has traditionally been considered a less partisan chamber because it's relatively small membership might have a better chance to broker compromises.