Background

The Great Depression was a time of significant upheaval in the United States. One of the most original contributions to understanding what had gone wrong came from a Harvard University lawyer, named Adolf Berle (1895–1971). Berle, who like John Maynard Keynes had resigned from his diplomatic job at the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, was deeply disillusioned by the Versailles Treaty. In his book with Gardiner C. Means, The Modern Corporation and Private Property (1932), he detailed the evolution in the contemporary economy of big business. Berle argued that the individuals who controlled big firms should be held accountable. Directors of companies are held accountable by the shareholders of companies. At times, they are not held accountable because of rules found in company law statutes. This might include the right to elect and fire the management, requirements for regular general meetings, accounting standards, and so on.

In the United States during the 1930's, the typical company laws (e.g. in Delaware) did not clearly mandate such rights. Berle argued that the unaccountable directors of companies were therefore apt to funnel the fruits of enterprise profits into their own pockets, as well as manage in their own interests. They were able to do this because the majority of shareholders in big public companies were single individuals, with scant means of communication. Quite simply, they divided and conquered. Berle served in President Franklin Delano Roosevelt's administration through the depression. He was also a key member of the so-called "Brain trust" that developed many of the New Deal policies. In 1967, Berle and Means issued a revised edition of their work, in which the preface added a new dimension. It was not only the separation of company directors from the owners as shareholders at stake. They posed the question of what the corporate structure was really meant to achieve.

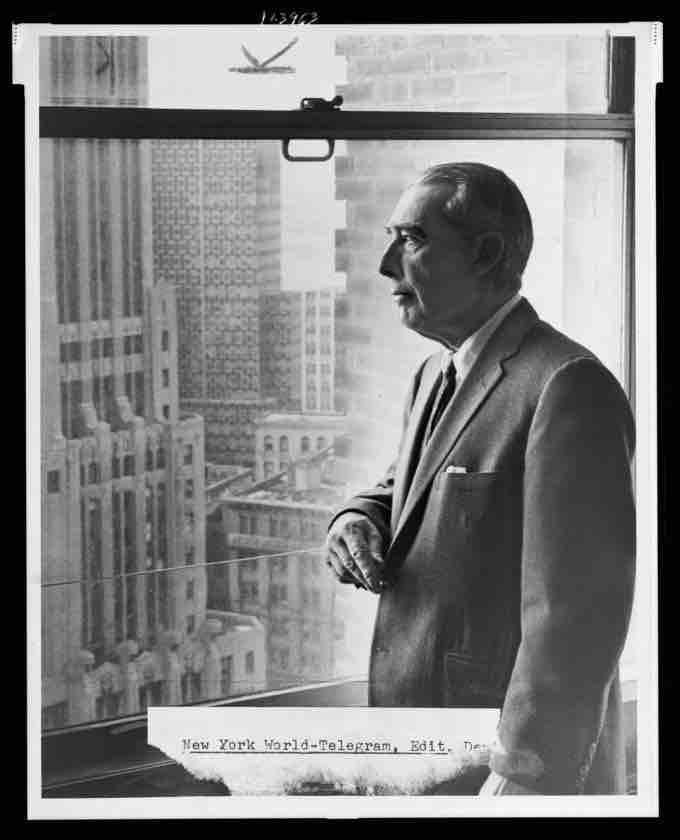

Adolf Augustus Berle

Adolf Berle, in The Modern Corporation and Private Property, argued that the separation of control of companies from the investors who were meant to own them endangered the American economy and led to a unequal distribution of wealth.

The Interaction with Public and Private Bureaucracies

After World War II, John Kenneth Galbraith (1908–2006) became one of the standard bearers for pro-active government and liberal-democrat politics. In The Affluent Society (1958), Galbraith urged voters reaching a certain material wealth begin to vote against the common good. He argued that the "conventional wisdom" of the conservative consensus was not enough to solve the problems of social inequality. In an age of big business, he argued, that it is unrealistic to think of markets of the classical kind. They set prices and use advertising to create artificial demand for their own products, which distorts people's real preferences. Consumer preferences actually come to reflect those of corporations—a "dependence effect"—and the economy as a whole is geared towards irrational goals.

In The New Industrial State, Galbraith argued that a private-bureaucracy, a techno-structure of experts who manipulated marketing and public relations channels, planned economic decisions. This hierarchy is self-serving, profits are no longer the prime motivator, and even managers are not in control. Since they are the new planners, corporations detest risk. They require steady economy and stable markets. They recruit governments to serve their interests with fiscaland monetary policy. An example would be adhering to monetarist policies that enrich moneylenders in the city through increases in interest rates. While the goals of an affluent society and complicit government serve the irrational techno-structure, public space is simultaneously impoverished. Galbraith paints the picture of stepping from penthouse villas onto unpaved streets, from landscaped gardens to unkempt public parks. In Economics and the Public Purpose (1973) Galbraith advocates a "new socialism" as the solution. He promotes nationalizing military production and public services such as health care as well as introducing disciplined salary and price controls to reduce inequality.

Today, the formation of private bureaucracies within the private corporate entities has created their own regulations and practices. Its organizational structure can be compared to that of a public bureaucracy. However, private bureaucracies still have to comply with public regulations imposed by the government. In addition, private enterprises continue to influence governmental structures. Therefore, the relationship is reciprocal.