Popular consent (or the consent of the governed), majority rule, and popular sovereignty are related concepts that form the basis of democratic government.

Consent of the Governed

"Consent of the governed" is a phrase synonymous with a political theory wherein a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is only justified and legal when derived from the people or society over which that political power is exercised. This theory of "consent" is historically contrasted to the "divine right of kings" and has often been invoked against the legitimacy of colonialism.

Using thinking similar to that of English philosopher John Locke, the founders of the United States believed in a state built upon the consent of "free and equal" citizens; a state otherwise conceived would lack legitimacy and legal authority. This idea was expressed, among other places, in the 2nd paragraph of the Declaration of Independence and in the Virginia Bill of Rights, especially Section 6, quoted below:

"That elections of members to serve as representatives of the people, in assembly, ought to be free; and that all men, having sufficient evidence of permanent common interest with, the attachment to, the community, have the right of suffrage , and cannot be taxed or deprived of their property for publick uses without their own consent, or that of their representatives so elected, nor bound by any law to which they have not, in like manner, assented, for the public good . "

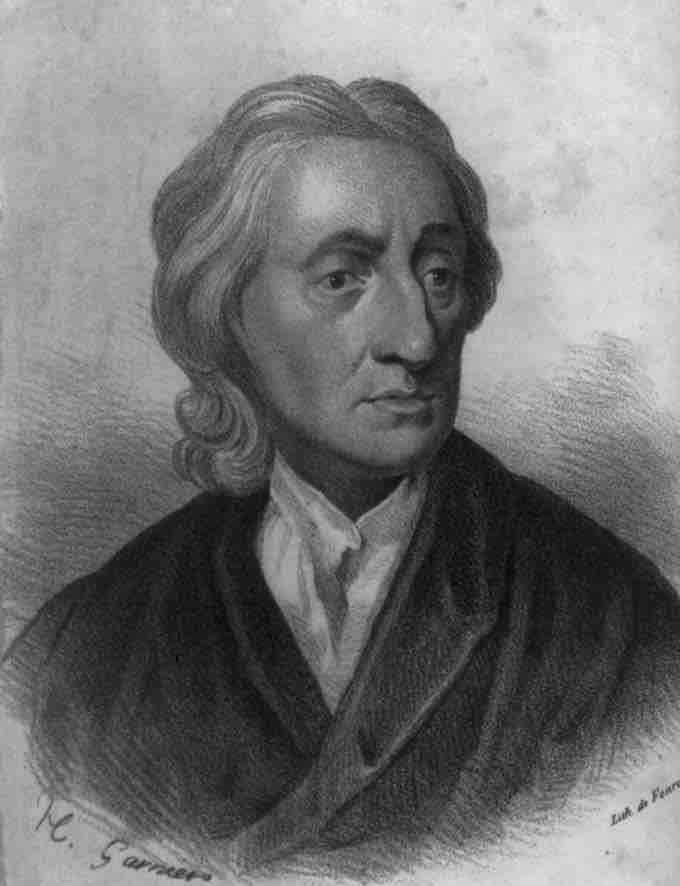

John Locke

John Locke was an English philosopher whose writings on the consent of the governed heavily influenced the founders of the United States

Majority Rule

Majority rule is a decision rule that selects the option which has more than half the votes. It is the decision rule used most often in influential decision-making bodies, including the legislatures of democratic nations. Some scholars have recommended against the use of majority rule, at least under certain circumstances, due to an ostensible trade-off between the benefits of majority rule and other values important to a democratic society. Most famously, it has been argued that majority rule might lead to a "tyranny of the majority," and the use of a supermajority and constitutional limits on government power have been recommended to mitigate these effects. Recently some voting theorists have argued that majority rule is the rule that best protects minorities.

Popular Sovereignty

Popular sovereignty in its modern sense, that is, including all the people and not just noblemen, is an idea that dates to the social contracts school (mid-17th to mid-18th centuries), represented by Thomas Hobbes (1588–1679), John Locke (1632–1704), and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), author of The Social Contract, a prominent political work that clearly highlighted the ideals of "general will" and further matured the idea of popular sovereignty. The central tenet is that legitimacy of rule or of law is based on the consent of the governed. Popular sovereignty is thus a basic tenet of most democracies. Whether men were seen as naturally more prone to violence and rapine (Hobbes) or cooperation and kindness (Rousseau), the idea that a legitimate social order emerges only when the liberties and duties are equal among citizens binds the social contract thinkers to the concept of popular sovereignty. Although Rousseau argues that sovereignty (or the power to make the laws) should be in the hands of the people, he also makes a sharp distinction between the sovereign and the government. The government is composed of magistrates, charged with implementing and enforcing the general will. The "sovereign" is the rule of law, ideally decided on by direct democracy in an assembly.

The American Revolution marked a departure in the concept of popular sovereignty as it had been discussed and employed in the European historical context. With the American Revolution, Americans substituted the sovereignty in the person of King George III, with a collective sovereign—one composed of the people. Thenceforth, American revolutionaries generally agreed and were committed to the principle that governments were legitimate only if they rested on popular sovereignty–that is, the sovereignty of the people. This idea—often linked with the notion of the consent of the governed—was not invented by the American revolutionaries. Rather, the consent of the governed and the idea of the people as a sovereign had clear 17th and 18th century intellectual roots in English history.