Overview

Pain is an unpleasant feeling often caused by intense or damaging stimuli, such as stubbing a toe, burning a finger, putting alcohol on a cut, and bumping the funny bone. The International Association for the Study of Pain's widely used definition states: "Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage, or described in terms of such damage."

Pain motivates the individual to withdraw from damaging situations, to protect a damaged body part while it heals, and to avoid similar experiences in the future. Most pain resolves promptly once the painful stimulus is removed and the body has healed, but sometimes pain persists despite removal of the stimulus and apparent healing of the body. Pain sometimes arises in the absence of any detectable stimulus, damage, or disease.

Nociceptors

A nociceptor is a sensory receptor that responds to potentially damaging stimuli by sending nerve signals to the spinal cord and brain. This process, called nociception, usually causes the perception of pain. There are several types and functions of nociceptors:

- Thermal nociceptors are activated by noxious heat or cold at various temperatures.

- Mechanical nociceptors respond to excess pressure or mechanical deformation. They also respond to incisions that break the skin surface. These mechanical nociceptors frequently have polymodal characteristics. So it is possible that some of the transducers for thermal stimuli are the same for mechanical stimuli.

- Chemical nociceptors respond to a wide variety of spices commonly used in cooking. The one that sees the most response and is very widely tested is capsaicin. Other chemical stimulants are environmental irritants like acrolein, a World War I chemical weapon and a component of cigarette smoke. Besides these external stimulants, chemical nociceptors have the capacity to detect endogenous ligands, and certain fatty acid amines that arise from changes in internal tissues.

The peripheral terminal of the mature nociceptor is where the noxious stimuli are detected and transduced into electrical energy. When the electrical energy reaches a threshold value, an action potential is induced and driven towards the central nervous system. This leads to the train of events that allows for the conscious awareness of pain.

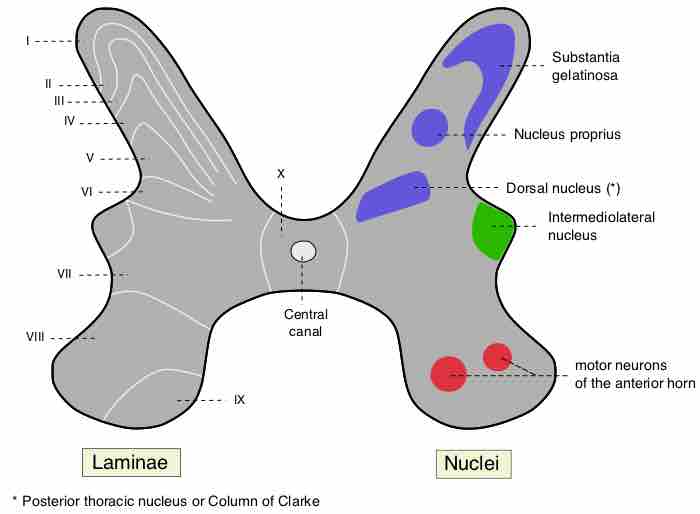

Gray matter in the spinal cord

A delta fibers (Aδ fibers), a type of sensory fiber, are associated with the sensation of cold and pressure. Aδ fibers are thinly myelinated; therefore, they conduct signals more rapidly than unmyelinated C fibers, but more slowly than other, more thickly myelinated "A" class fibers. Aδ fibers terminate at Rexed laminae I and V (labeled I and V in the diagram). C fibers respond to thermal, mechanical, and chemical stimuli and terminate at the Rexed lamina II (labeled II in the diagram).

Nociceptors have two different types of axons.

- The Aδ fiber axons are myelinated and can allow an action potential to travel at a rate of about 20 meters/second towards the central nervous system.

- The other type is the more slowly conducting C fiber axons. These only conduct at speeds of around 2 meters/second. This is due to the light or nonmyelination of the axon.

Phases of Pain

Pain comes in two phases. The first phase is mediated by the fast-conducting Aδ fibers, and the second part is due to C fibers. The pain associated with the Aδ fibers can be associated to an initial extremely sharp pain.

The second phase is a more prolonged and slightly less intense feeling of pain as a result of the damage. If there is massive or prolonged input to a C fiber, there is a progressive build up in the spinal cord dorsal horn; this phenomenon is similar to tetanus in muscles but is called wind-up. If wind-up occurs, there is a probability of increased sensitivity to pain.

Although each nociceptor can have a variety of possible threshold levels, some do not respond at all to chemical, thermal, or mechanical stimuli unless injury actually has occurred. These are typically referred to as silent or sleeping nociceptors since their response comes only at the onset of inflammation to the surrounding tissue.

Types of Nociceptive Pain

Nociceptive pain can be divided into visceral, deep somatic and superficial somatic pain.

- Visceral structures are highly sensitive to stretch, ischemia, and inflammation, but relatively insensitive to other stimuli that normally evoke pain in other structures, such as burning and cutting. Visceral pain is diffuse, difficult to locate, and often referred to a distant, usually superficial, structure. It may be accompanied by nausea and vomiting and may be described as sickening, deep, squeezing, and dull.

- Deep somatic pain is initiated by stimulation of nociceptors in ligaments, tendons, bones, blood vessels, fasciae and muscles, and is a dull, aching, poorly localized pain. Examples include sprains and broken bones.

- Superficial pain is initiated by the activation of nociceptors in the skin or other superficial tissue, and is sharp, well-defined, and clearly located. Examples of injuries that produce superficial somatic pain include minor wounds and minor (first degree) burns.