A symphysis, a type of secondary cartilaginous joint, is a fibrocartilaginous fusion between two bones. It is an amphiarthrosis (slightly movable) joint, and an area where two parts or structures grow together. Unlike synchondroses, symphyses are permanent. The more prominent symphyses are the pubic symphysis; the symphyses between the bones of the skull, most notably the mandible (symphysis menti); sacrococcygeal symphysis; the intervertebral disc between two vertebrae; and in the sternum, between the manubrium and body, and between the body and xiphoid process.

Symphyses

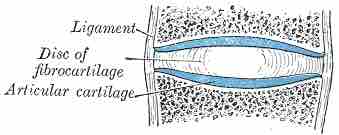

Diagrammatic section of a symphysis including the ligament, disc of fibrocartilage, and articular cartilage.

Pubic Symphysis

The pubic symphysis or symphysis pubis is the midline cartilaginous joint (secondary cartilaginous) uniting the superior rami of the left and right pubic bones. It is a nonsynovial amphiarthrodial joint connected by fibrocartilage, and may contain a fluid-filled cavity. The ends of both pubic bones are covered by a thin layer of hyaline cartilage attached to the fibrocartilage.

The pubic symphysis is located anterior to the urinary bladder and superior to the external genitalia, above the vulva in females and above the penis in males. The suspensory ligament of the penis attaches to the pubic symphysis. In females, the pubic symphysis is intimately close to the clitoris. In normal adults, it can be moved roughly two mm and with one degree of rotation. Mobility of this joint increases for women at the time of childbirth. During birth, the pubic symphysis of relaxes to slightly widen the birth canal. This movement is minimal, but along with the compression of the unfused fetal skull generally allows an infant to be born vaginally.

The pubic symphysis widens slightly whenever the legs are stretched far apart. In sports in which this movement is frequent, the risk of a pubic symphysis blockage is high. This injury occurs when the bones at the symphysis do not realign correctly after completion of the movement and get jammed in a dislocated position. The resulting pain can be quite severe, especially if further strain is put upon the affected joint. In most cases, the joint can only be successfully reduced into its normal position by a trained medical professional.

Pubic symphyses have importance in the field of forensic anthropology, as they can be used to estimate the age of adult skeletons. Throughout life, the surfaces become worn at a more or less predictable rate. By examining the wear of the pubic symphysis, it is possible to estimate the age of the person at death.

Mandible

The external surface of the mandible is marked in the median line by a faint ridge, indicating the symphysis menti, mandibular symphysis, or line of junction. This line delineates the two pieces of bone that compose the mandible during the first years of life.

Intervertebral Discs

Intervertebral discs (or intervertebral fibrocartilage) lie between adjacent vertebrae in the spine. Each disc forms a cartilaginous joint to allow slight movement of the vertebrae and acts as a ligament to hold the vertebrae together. The discs consist of an outer annulus fibrosus that surrounds the inner nucleus pulposus. The annulus fibrosus and the nucleus pulposus distribute pressure evenly across the disc.

The nucleus pulposus contains loose fibers suspended in a mucoprotein gel with the consistency of jelly. The nucleus of the disc acts as a shock absorber, absorbing the impact of the body's daily activities and keeping the two vertebrae separated. The disc can be likened to a jelly doughnut with the annulus fibrosis as the dough and the nucleus pulposis as the jelly. If one presses down on the front of the doughnut, the jelly moves posteriorly. When one develops a prolapsed disc, the jelly (the nucleus pulposus) is forced out of the doughnut (the disc) and may put pressure on the nerve located near the disc, potentially causing symptoms of sciatica.

Diagram of Invertebral Disc

The lateral and superior view of an invertebral disc, including the vertebral body, intervertebral foramen, anulus fibrosis, and nucleus pulposus.

Aging causes disc degeneration, in which the nucleus pulposus begins to dehydrate and the concentration of proteoglycans in the matrix decreases, limiting the ability of the disc to absorb shock. This general shrinking of disc size is partially responsible for the common decrease in height as humans age.