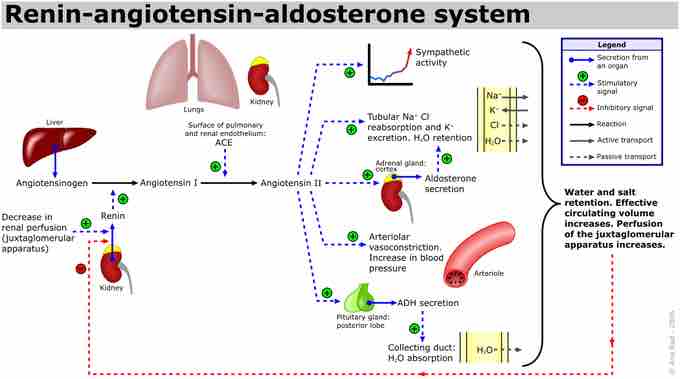

Along with vessel morphology, blood viscosity is one of the key factors influencing resistance and hence blood pressure. A key modulator of blood viscosity is the renin-angiotensin system (RAS) or the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system (RAAS), a hormone system that regulates blood pressure and water balance.

When blood volume is low, juxtaglomerular cells in the kidneys secrete renin directly into circulation. Plasma renin then carries out the conversion of angiotensinogen released by the liver to angiotensin I. Angiotensin I is subsequently converted to angiotensin II by the enzyme angiotensin converting enzyme found in the lungs. Angiotensin II is a potent vasoactive peptide that causes blood vessels to constrict, resulting in increased blood pressure. Angiotensin II also stimulates the secretion of the hormone aldosterone from the adrenal cortex.

Aldosterone causes the tubules of the kidneys to increase the reabsorption of sodium and water into the blood. This increases the volume of fluid in the body, which also increases blood pressure. If the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system is too active, blood pressure will be too high. Many drugs interrupt different steps in this system to lower blood pressure. These drugs are one of the main ways to control high blood pressure (hypertension), heart failure, kidney failure, and harmful effects of diabetes.

It is believed that angiotensin I may have some minor activity, but angiotensin II is the major bioactive product. Angiotensin II has a variety of effects on the body: throughout the body, it is a potent vasoconstrictor of arterioles.

The renin-angiotensin pathway

The figures outlines the origination of the renin-angiotensin pathway molecules, as well as effects on target organs and systems.