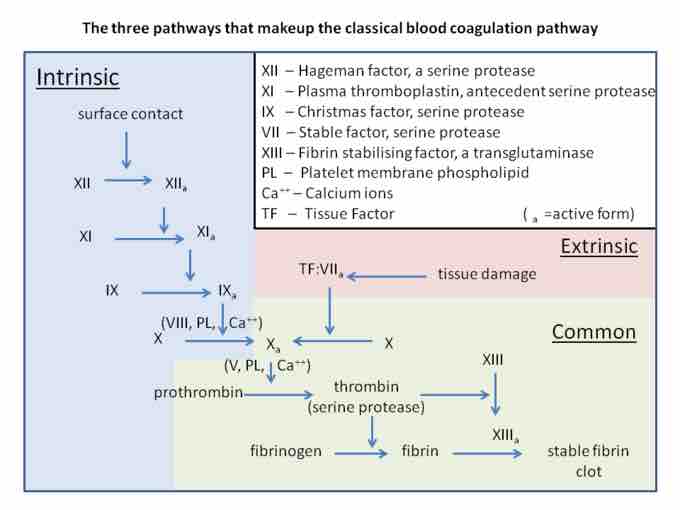

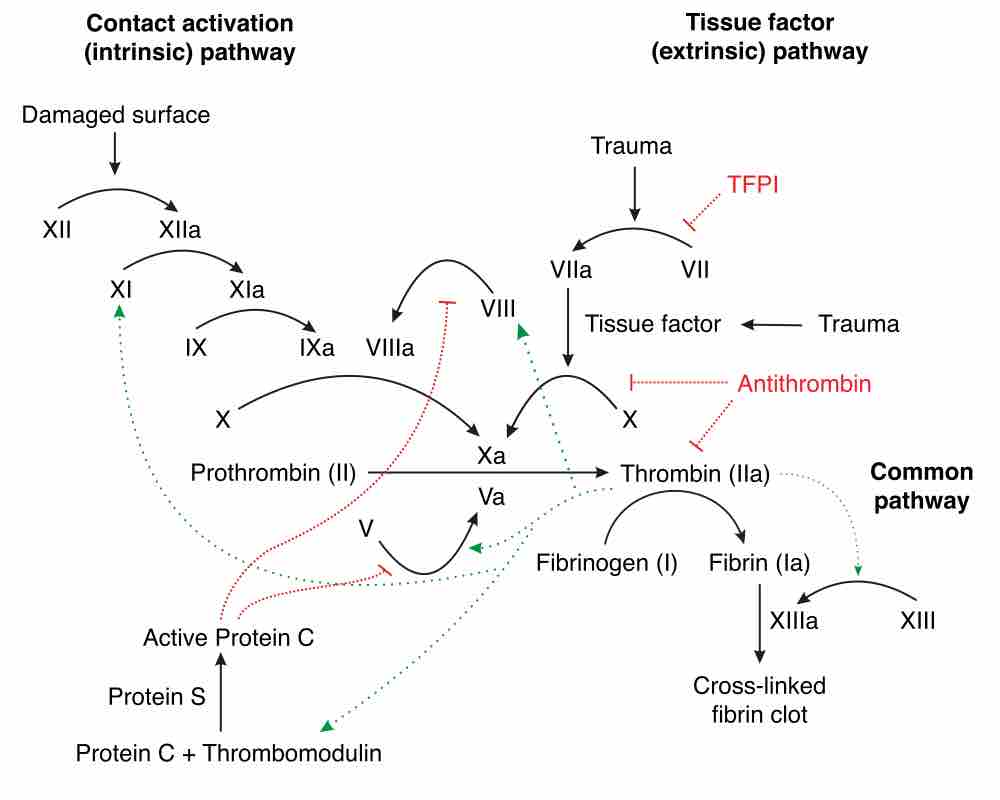

Coagulation is the process by which a blood clot forms to reduce blood loss after damage to a blood vessel. Several components of the coagulation cascade, including both cellular (e.g. platelets) and protein (e.g. fibrin) components, are involved in blood vessel repair. The role of the cellular and protein components can be categorized as primary hemostasis (the platelet plug) and secondary hemostasis (the coagulation cascade). The coagulation cascade is classically divided into three pathways: the contact (also known as the intrinsic) pathway, the tissue factor (also known as the extrinsic pathway), and the common pathway. Both the contact pathway and the tissue factor feed into and activate the common pathway.

Secondary Hemostasis

Hemostasis can either be primary or secondary. Primary hemostasis refers to platelet plug formation, which forms the primary clot. Secondary hemostasis refers to the coagulation cascade, which produces a fibrin mesh to strengthen the platelet plug. Secondary hemostasis occurs simultaneously with primary hemostasis, but generally finishes after it. The coagulation factors circulate as inactive enzyme precursors, which, upon activation, take part in the series of reactions that make up the coagulation cascade. The coagulation factors are generally serine proteases (enzymes).

Coagulation Pathway

Coagulation Cascade

Intrinsic Pathway

The intrinsic pathway (contact activation pathway) occurs during exposure to negatively charged molecules, such as molecules on bacteria and various types of lipids. It begins with formation of the primary complex on collagen by high-molecular-weight kininogen (HMWK), prekallikrein, and factor XII (Hageman factor). This initiates a cascade in which factor XII is activated, which then activates factor XI, which activated factor IX, which along with factor VIII activates factor X in the common pathway.

Extrinsic Pathway

The main role of the extrinsic (tissue factor) pathway is to generate a "thrombin burst," a process by which large amounts of thrombin, the final component that cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, is released instantly. The extrinsic pathway occurs during tissue damage when damaged cells release tissue factor III. Tissue factor III acts on tissue factor VII in circulation and feeds into the final step of the common pathway, in which factor X causes thrombin to be created from prothrombin.

Common Pathway

In the final common pathway, prothrombin is converted to thrombin. When factor X is activated by either the intrinsic or extrinsic pathways, it activates prothrombin (also called factor II) and converts it into thrombin using factor V. Thrombin then cleaves fibrinogen into fibrin, which forms the mesh that binds to and strengthens the platelet plug, finishing coagulation and thus hemostasis. It also activates more factor V, which later acts as an anticoagulant with inhibitor protein C, and factor XIII, which covalently bonds to fibrin to strengthen its attachment to the platelets.

Coagulation Problems

While the coagulation cascade is critical for hemostasis and wound healing, it can also cause problems. An embolism is any thrombosis (blood clot) that breaks off without being dissolved and travels through the bloodstream to another site. If it obstructs an artery that supplies blood to a tissue or organ, it can cause ischemia and infarcation to those tissues, leading to a pulmonary embolism, stroke, or heart attack).

Coagulation can occur even without injury, as blood pooling from prolonged immobility can cause clotting factors to accumulate and activate a coagulation cascade independently. Additionally, endothelial damage caused by immune system factors like inflammation or hypersensitivity may also cause unnecessary thrombosis and embolism. For example, during severe bacterial infections (septic shock), inflammation-induced tissue damage and the negatively charged molecules of bacteria activate both pathways of the coagulation cascade and cause disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), in which many clots form and break off, leading to massive organ failure.

Anticoagulants

Many anticoagulants prevent unnecessary coagulation, and those that genetically lack the ability to produce these molecules will be more susceptible to coagulation. These mechanisms include:

- Protein C: a vitamin K-dependent serine protease enzyme that degrades Factor V and factor VIII.

- Antithrombin: a serine protease inhibitor that degrades thrombin, Factor IXa, Factor Xa, Factor XIa, and Factor XIIa.

- Tissue factor pathway inhibitor (TFPI): limits the action of tissue factor (TF) and the factors it produces.

- Plasmin: generated by proteolytic cleavage of plasminogen, a potent fibrinolytic that degrades fibrin and destroys clots.

- Prostacyclin (PGI2): released by the endothelium and inhibits platelet activation.

- Thrombomodulin: released by the endothelium and converts thrombin into an inactive form.