A prion is an infectious agent composed of protein in a misfolded form. This is the central idea of the Prion Hypothesis, which remains debated. This is in contrast to all other known infectious agents (virus/bacteria/fungus/parasite) which must contain nucleic acids (either DNA, RNA, or both).

The word prion, coined in 1982 by Stanley B. Prusiner, is derived from the words protein and infection. Prions are responsible for the transmissible spongiform encephalopathies in a variety of mammals, including bovine spongiform encephalopathy (BSE, also known as "mad cow disease") in cattle and Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease (CJD) in humans. All known prion diseases affect the structure of the brain or other neural tissue, are currently untreatable and universally fatal.

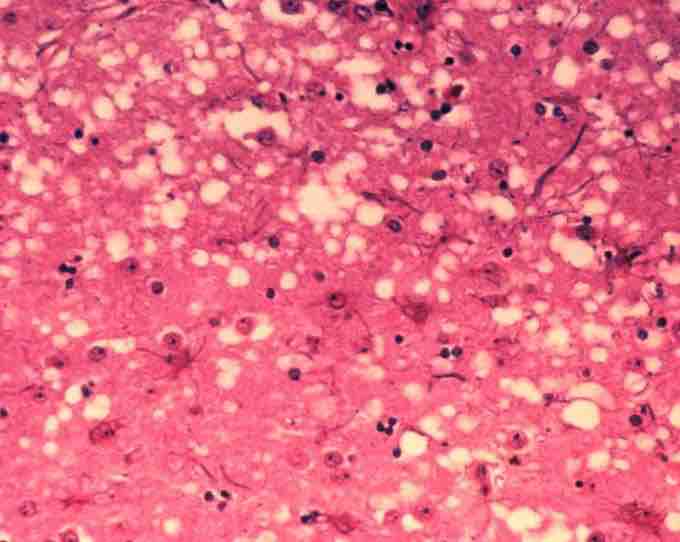

Prion-affected tissue

This micrograph of brain tissue reveals the cytoarchitectural histopathologic changes found in bovine spongiform encephalopathy. The presence of vacuoles, i.e. microscopic "holes" in the gray matter, gives the brain of BSE-affected cows a sponge-like appearance when tissue sections are examined in the lab.

Prions propagate by transmitting a misfolded protein state. When a prion enters a healthy organism, it induces existing, properly folded proteins to convert into the disease-associated prion form; it acts as a template to guide the misfolding of more proteins into prion form. These newly-formed prions can then go on to convert more proteins themselves; triggering a chain reaction. All known prions induce the formation of an amyloid fold, in which the protein polymerises into an aggregate consisting of tightly-packed beta sheets. Amyloid aggregates are fibrils, growing at their ends, and replicating when breakage causes two growing ends to become four growing ends.

The incubation period of prion diseases is determined by the exponential growth rate associated with prion replication, which is a balance between the linear growth and the breakage of aggregates. Propagation of the prion depends on the presence of normally-folded protein in which the prion can induce misfolding; animals which do not express the normal form of the prion protein cannot develop nor transmit the disease.

All known mammalian prion diseases are caused by the so-called prion protein, PrP. The endogenous, properly-folded form is denoted PrPC (for Common or Cellular) while the disease-linked, misfolded form is denoted PrPSc (for Scrapie, after one of the diseases first linked to prions and neurodegeneration. ) The precise structure of the prion is not known, though they can be formed by combining PrPC, polyadenylic acid, and lipids in a Protein Misfolding Cyclic Amplification (PMCA) reaction.

Proteins showing prion-type behavior are also found in some fungi, which has been useful in helping to understand mammalian prions. Fungal prions do not appear to cause disease in their hosts.

The first hypothesis that tried to explain how prions replicate in a protein-only manner was the heterodimer model . This model assumed that a single PrPSc molecule binds to a single PrPC molecule and catalyzes its conversion into PrPSc. The two PrPSc molecules then come apart and can go on to convert more PrPC. However, a model of prion replication must explain both how prions propagate, and why their spontaneous appearance is so rare. Manfred Eigen showed that the heterodimer model requires PrPSc to be an extraordinarily effective catalyst, increasing the rate of the conversion reaction by a factor of around 1015. This problem does not arise if PrPSc exists only in aggregated forms such as amyloid, where cooperativity may act as a barrier to spontaneous conversion. What is more, despite considerable effort, infectious monomeric PrPSc has never been isolated.

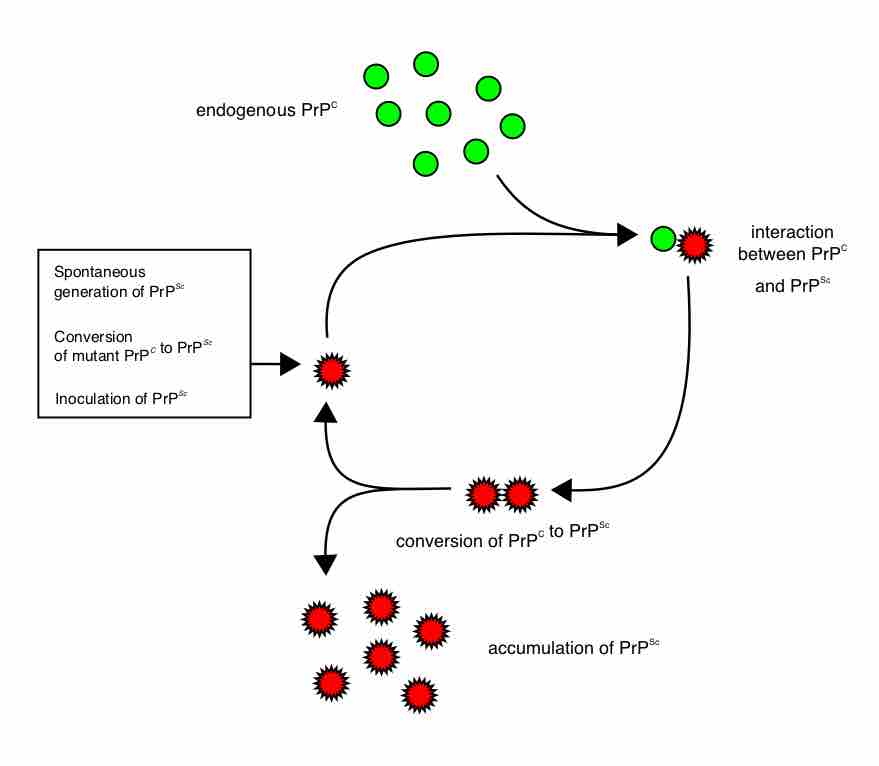

Diagram demonstrating how prion numbers increase

Heterodimer model of prion propagation.

An alternative model assumes that PrPSc exists only as fibrils , and that fibril ends bind PrPC and convert it into PrPSc. If this were all, then the quantity of prions would increase linearly, forming ever longer fibrils. But exponential growth of both PrPSc and of the quantity of infectious particles is observed during prion disease. This can be explained by taking into account fibril breakage. A mathematical solution for the exponential growth rate resulting from the combination of fibril growth and fibril breakage has been found.

The Fibril Model

Illustrating prion propagation.

The protein-only hypothesis has been criticised by those who feel that the simplest explanation of the evidence to date is viral. For more than a decade, Yale University neuropathologist Laura Manuelidis has been proposing that prion diseases are caused instead by an unidentified slow virus. In January 2007, she and her colleagues published an article reporting to have found a virus in 10%, or less, of their scrapie-infected cells in culture.

The virion hypothesis states that TSEs are caused by a replicable informational molecule (likely to be a nucleic acid) bound to PrP. Many TSEs, including scrapie and BSE, show strains with specific and distinct biological properties, a feature which supporters of the virion hypothesis feel is not explained by prions.

Recent studies propagating TSE infectivity in cell-free reactions and in purified component chemical reactions strongly suggest against TSE's viral nature. Using a similar defined recipe of multiple components (PrP, POPG lipid, RNA), Jiyan Ma and colleagues generated infectious prions from recombinant PrP expressed from E. coli, casting further doubt on this hypothesis.