Deep sea communities currently remain largely unexplored, due the technological and logististical challenges, and the expense involved in visiting these remote biomes. Because of the unique challenges (particularly the high barometric pressure, extremes of temperature, and absence of light), it was long believed that little life existed in this hostile environment. Since the 19th century however, research has demonstrated that significant biodiversity exists in the deep sea.

The three main sources of energy and nutrients for deep sea communities are marine snow, whale falls, and chemosynthesis at hydrothermal vents and cold seeps.

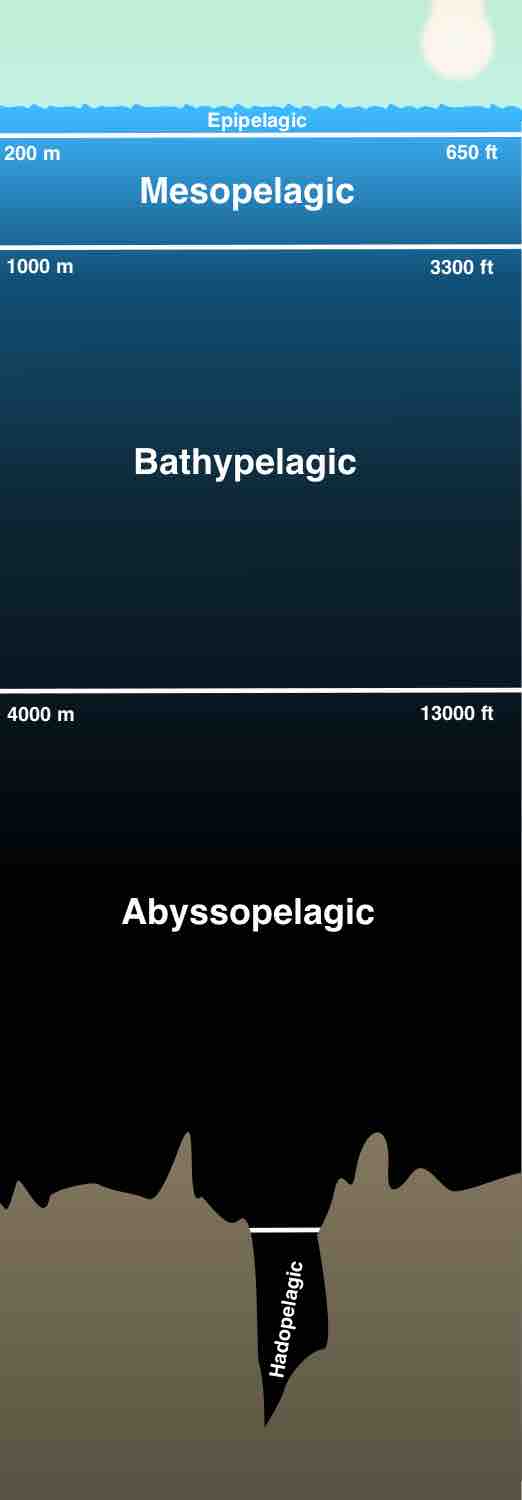

Zones of the deep sea include the mesopelagic zone, the bathyal zone, the abyssal zone, and the hadal zone.

Deep Sea Pelagic Zones

Mesopelagic, bathyl, abyssal, and hadal zones.

A piezophile, also called a barophile, is an organism which thrives at high pressures, such as deep sea bacteria or archaea. They are generally found on ocean floors, where pressure often exceeds 380 atm (38 MPa). Some have been found at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean where the maximum pressure is roughly 117 MPa. The high pressures experienced by these organisms can cause the normally fluid cell membrane to become waxy and relatively impermeable to nutrients. These organisms have adapted in novel ways to become tolerant of these pressures in order to colonize deep sea habitats. One example, xenophyophores, have been found in the deepest ocean trench, 6.6 miles (10,541 meters) below the surface.

Barotolerant bacteria are able to survive at high pressures, but can exist in less extreme environments as well. Obligate barophiles cannot survive outside of such environments. For example, the Halomonas species Halomonas salaria requires a pressure of 1000 atm (100 MPa) and a temperature of three degrees Celsius. Most piezophiles grow in darkness and are usually very UV-sensitive; they lack many mechanisms of DNA repair.