A government's budget balance is determined by the difference in revenues (primarily taxes) and spending. A positive balance is a surplus, and a negative balance is a deficit. The consequences of a budget deficit depend on the type of deficit .

U.S. Budget Deficits

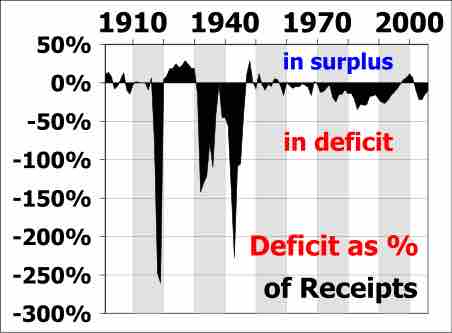

The graph shows the budget deficits and surpluses incurred by the U.S. government between 1901 and 2006. Although deficits may have an expansionary effect, this is not the primary purpose of running a deficit.

Cyclical Deficits

A cyclical deficit is a deficit incurred due to the ups and downs of a business cycle. At the lowest point in the business cycle, there is a high level of unemployment. This means that tax revenues are low and expenditures (e.g., on social security and unemployment benefits) are high, naturally leading to a budget deficit. Conversely, at the peak of the cycle, unemployment is low, increasing tax revenue and decreasing spending, which leads to a budget surplus. The additional borrowing required at the low point of the cycle is the cyclical deficit. By definition, the cyclical deficit will be entirely repaid by a cyclical surplus at the peak of the cycle.

This type of budget deficit serves as a stabilizer, insulating individuals from the effects of the business cycle without any specific legislation or other intervention. This is because budget deficits can have stimulative effects on the economy, increasing demand, spending, and investment. Higher spending on transfer payments puts more money into the economy, supporting demand and investment. Furthermore, lower revenues mean that more money is left in the hands of individuals and businesses, encouraging spending. As the economy grows more quickly, the budget deficit falls and the fiscal stimulus is slowly removed.

Structural Deficits

The structural deficit is the deficit that remains across the business cycle because the general level of government spending exceeds prevailing tax levels. Structural deficits are permanent, and occur when there is an underlying imbalance between revenues and expenses.

This is the budget gap still exists when the economy is at full employment and producing at full potential output levels. It can only be closed by increasing revenues or cutting spending. Unlike the cyclical budget deficit, a structural deficit is the result of discretionary, not automatic, fiscal policy. While automatic stabilizers don't actually shift the aggregate demand curve (because transfer payments and taxes are already built into aggregate demand), discretionary fiscal policy can shift the aggregate demand curve. For example, if the government decides to implement a new program to build military aircraft without adjusting any sources of revenue, aggregate demand will shift to the right, raising prices and output.

Although both types of government budget deficits are typically expansionary during a recession, a structural deficit may not always be expansionary when the economy is at full employment. This is due to a phenomenon called crowding out. When an increase in government expenditure or a decrease in government revenue increases the budget deficit, the Treasury must issue more bonds. This reduces the price of bonds, raising the interest rate. The increase in the interest rate reduces the quantity of private investment demanded (crowding out private investment). The higher interest rate increases the demand for and reduces the supply of dollars in the foreign exchange market, raising the exchange rate. A higher exchange rate reduces net exports. All of these effects work to offset the increase in aggregate demand that would normally accompany an increase in the budget deficit.