A frame in social theory consists of a schema of interpretation that individuals rely on to understand and respond to events. In other words, people build a series of mental filters through biological and cultural influences and use those filters to understand the world. Their choices are influenced by their frames.

Explanation

When one seeks to explain an event, the understanding often depends on the individual's frame. If a friend rapidly closes and opens an eye, we will respond very differently depending on whether we attribute this to a purely "physical" frame (s/he blinked) or to a social frame (s/he winked).

Though the former might result from a speck of dust (resulting in an involuntary and not particularly meaningful reaction), the latter would imply a voluntary and meaningful action (e.g., to convey humor to an accomplice).

People do not look at an event and then "apply" a frame to it; people constantly project into the world around them the interpretive frames that allow them to make sense of it. People only shift frames when incongruity calls for a frame shift. In other words, people only become aware of the frames that they already use when something forces them to replace one frame with another.

Framing is so effective because it is a heuristic, or a mental shortcut that may not always yield desired results and is seen as a "rule of thumb. " . According to Susan T. Fiske and Shelley E. Taylor, human beings are by nature "cognitive misers," meaning they prefer to do as little thinking as possible. Frames provide people a quick and easy way to process information. Hence, people will use the previously mentioned mental filters (a series of which is called a "schema") to make sense of incoming messages. This gives the sender and framer of the information enormous power to use these schemas to influence how the receivers will interpret the message.

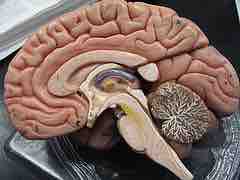

The Brain's Heuristics for Emotions

Emotions appear to aid the decision-making process.

The Framing of Problems

Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman have shown that framing can affect the outcome (i.e., the choices one makes) of choice problems, to the extent that several of the classic axioms of rational choice do not hold. This led to the development of the prospect theory as an alternative to rational choice theory.

The context or framing of problems adopted by decision makers results in part from extrinsic manipulation of the decision options offered, as well as from forces intrinsic to decision makers (e.g., their norms, habits, and unique temperament).

Experimental Demonstration

Tversky and Kahneman (1981) demonstrated systematic reversals of preference when the same problem is presented in different ways, for example, in the Asian disease problem. Participants were asked to "imagine that the U.S. is preparing for the outbreak of an unusual Asian disease, which is expected to kill 600 people. Two alternative programs to combat the disease have been proposed. Assume the exact scientific estimate of the consequences of the programs are as follows. "

The first group of participants was presented with a choice between programs: In a group of 600 people, Program A: "200 people will be saved;" Program B: "there is a one-thirds probability that 600 people will be saved, and a two-thirds probability that no people will be saved. " Of participants, 72% preferred program A (the remainder, 28%, opted for program B).

The second group of participants was presented with the choice between the following: In a group of 600 people, Program C: "400 people will die" Program D: "there is a one-third probability that nobody will die, and a two-thirds probability that 600 people will die"

In this decision frame, 78% preferred program D, with the remaining 22% opting for program C.

Programs A and C are identical, as are programs B and D. The change in the decision frame between the two groups of participants produced a preference reversal: When the programs were presented in terms of lives saved, the participants preferred the secure program, A (= C). When the programs were presented in terms of expected deaths, participants chose the gamble D (= B).

Absolute and Relative Influences

Framing effects arise because one can frequently frame a decision using multiple scenarios, wherein one may express benefits either as a relative risk reduction (RRR), or as absolute risk reduction (ARR). Extrinsic control over the cognitive distinctions (between risk tolerance and reward anticipation), adopted by decision makers, can occur through altering the presentation of relative risks and absolute benefits.

People generally prefer the absolute certainty inherent in a positive framing-effect, which offers an assurance of gains. When decision options appear framed as a likely gain, risk-averse choices predominate.

A shift toward risk-seeking behavior occurs when a decision maker frames decisions in negative terms or adopts a negative framing effect.