Entrepreneurial Economics

Entrepreneurial economics is the study of the entrepreneur and entrepreneurship within the economy. The accumulation of factors of production per se does not explain economic development. They are necessary inputs in production, but they are not sufficient for economic growth. Human creativity and productive entrepreneurship are needed to combine these inputs in profitable ways, and hence an institutional environment that encourages free entrepreneurship becomes the ultimate determinant of economic growth. Thus, the entrepreneur and entrepreneurship should take center stage in any effort to explain long-term economic development. Early economic theory, however did not pay proper attention to the entrepreneur. As William J. Baumol observed in the American Economic Review, "The theoretical firm is entrepreneurless—the Prince of Denmark has been expunged from the discussion of Hamlet." The article was a prod to the economics profession to attend to this neglected factor. If entrepreneurship remains as important to the economy as ever, then the continuing failure of mainstream economics to adequately account for entrepreneurship indicates that fundamental principles require re-evaluation. The characteristics of an entrepreneurial economy are high levels of innovation combined with high level of entrepreneurship which result in the creation of new ventures as well as new sectors and industries. Entrepreneurship is difficult to analyze using the traditional tools of economics e.g. calculus and general equilibrium models.

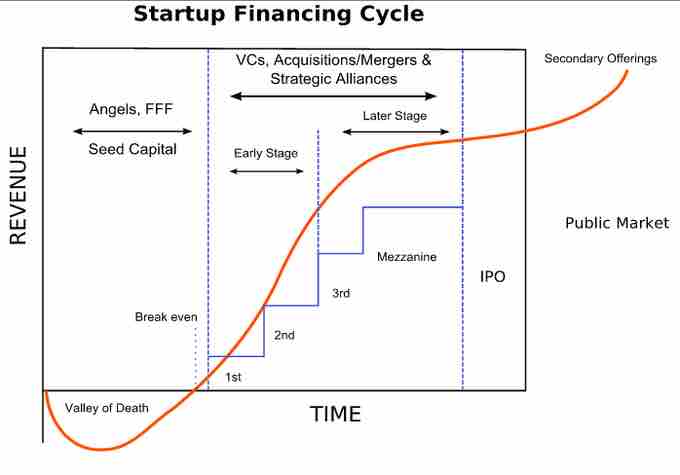

Startup financing cycle

Diagram of the typical financing cycle for a startup company

Equilibrium models are central to mainstream economics, and exclude entrepreneurship. Joseph Schumpeter and Israel Kirzner argued that entrepreneurs do not tolerate equilibrium.

Studies about entrepreneurs in Economics, Psychology and Sociology largely relate to four major currents of thought. Early thinkers such as Max Weber emphasized its occurrence in the context of a religious belief system, thereby suggesting that some belief systems do not encourage entrepreneurship. This contention has, however, been challenged by many sociologists. Some thinkers such as K Samuelson believe that there is no relationship between religion, economic development and entrepreneurship. Karl Marx considered the economic system and mode of production as its sole determinants. Weber suggested a direct relation between the ethics and economic system as both intensively interacted. Another current of thought underscores the motivational aspects of personal achievement. This overemphasized the individual and his values, attitudes and personality. This thought, however, has been severely criticized by many scholars such as Kilby (1971) and Kunkel (1971).

Economists of the 1930s and the Acknowledgement of Entrepreneurship

Entrepreneurship is a factor in microeconomics, and its study reaches back to the work of Richard Cantillon and Adam Smith in the late 17th and early 18th centuries. It was ignored theoretically until the late 19th and early 20th centuries and empirically until a profound resurgence in business and economics in the last 40 years. In the 20th century, the understanding of entrepreneurship owes much to the work of Joseph Schumpeter in the 1930s and other Austrian economists such as Carl Menger, Ludwig von Mises and Friedrich von Hayek. To Schumpeter, an entrepreneur is a person willing and able to convert a new idea or invention into a successful innovation. Entrepreneurship employs what Schumpeter called "the gale of creative destruction" to replace in whole or in part inferior innovations across markets and industries, simultaneously creating new products and business models. In this way, creative destruction is largely responsible for the dynamism of industries and long-run economic growth. The supposition that entrepreneurship leads to economic growth is an interpretation of the residual in endogenous growth theory and as such is hotly debated in academic economics. An alternate description posited by Israel Kirzner suggests that the majority of innovations may be much more incremental improvements such as the replacement of paper with plastic in the construction of a drinking straw.

For Schumpeter, entrepreneurship resulted in new industries but also in new combinations of currently existing inputs. Schumpeter's initial example of this was the combination of a steam engine and then current wagon-making technologies to produce the horseless carriage. In this case the innovation, the car, was transformational but did not require the development of a new technology, merely the application of existing technologies in a novel manner. It did not immediately replace the horsedrawn carriage, but in time, incremental improvements which reduced the cost and improved the technology led to the complete practical replacement of beast drawn vehicles in modern transportation. Despite Schumpeter's early 20th-century contributions, traditional microeconomic theory did not formally consider the entrepreneur in its theoretical frameworks (instead assuming that resources would find each other through a price system). In this treatment the entrepreneur was an implied but unspecified actor, but it is consistent with the concept of the entrepreneur being the agent of x-efficiency. Different scholars have described entrepreneurs as, among other things, bearing risk. For Schumpeter, the entrepreneur did not bear risk: the capitalist did.