Roman painters often painted frescoes, specifically buon fresco, a technique that involved painting pigment on wet plaster. When the painting dried, the image became an integral part of the wall. Fresco painting was the primary method of decorating an interior space. However, few examples survive, and the majority of them are from the remains of Roman houses and villas around Mt. Vesuvius. Other examples of frescoes come from locations that were buried, such as parts of Nero's Domus Aurea and at the Villa of Livia. Burial protected and preserved the frescoes, which demonstrate a wide variety of styles. Popular subjects include mythology, portraiture, still-life painting, and historical accounts.

The surviving Roman paintings reveal the high degree of sophistication, employing visual techniques that include atmospheric and near one-point linear perspective to properly convey the idea of space. Furthermore, portraiture and still-life images demonstrate artistic talent when conveying real-life objects and likenesses. The attention to detail seen in still-life paintings include minute shadows and attention to light to properly depict the material of the object, whether it be glass, food, ceramics, or animals.

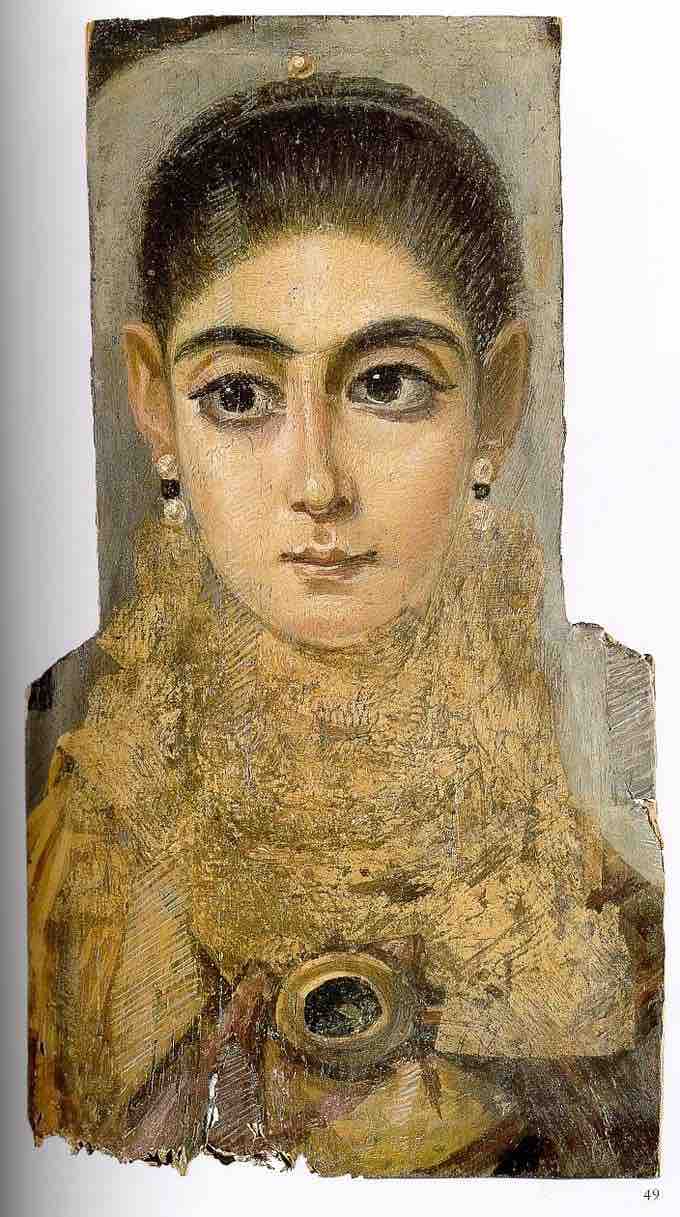

Roman portraiture further exhibits the talent of Roman painters and often shows careful study on the artist's part in the techniques used to portray individual faces and people. Some of the most interesting portraits come from Egypt, from late first century BCE to early third century CE, when Egypt was a province of Rome. These encaustic on wood panel images from the Fayum necropolis were laid over the mummified body. They show remarkable realism, while conveying the ideals and changing fashions of the Egypto-Roman people.

Fayum Mummy Portrait

A mummy portrait of a young women. Fayum Necropolis, Egypt. Second century CE.

Classification

At the end of the nineteenth century, August Mau, a German art historian, studied and classified Roman styles of painting at Pompeii. These styles, known simply as Pompeian First, Second, Third, and Fourth Style, demonstrate period fashions of interior decoration preferences and changes in taste and style from the Republic through the early Empire.

First Style

Also known as masonry style, Pompeian First Style painting was most commonly used from 200 to 80 BCE. The style is known for its deceptive painting of a faux surface; the painters often tried to mimic richly veneered surfaces of marble, alabaster, and other expensive types of stone veneer. This is a Hellenistic (Greek) style adopted by the Romans. While creating an illusion of expensive decor, First-Style painting reinforces the idea of a wall. The style is often found in the fauces (entrance hall) and atrium (large open-air room) of a Roman domus (house). A vivid example is preserved in the fauces of the Samnite House at Herculaneum.

Pompeian First Style Wall

Pompeiian first style wall painting from the Samnite House. Fresco. Second century BCE. Herculaneum, Italy.

Second Style

Pompeiian Second Style was first used around 80 BCE and was especially fashionable from 40 BCE onward, until its popularity waned in the final decades of the first century BCE. The style is noted for its visual illusions. These trompe l'oeil images are intended to trick the eye into believing that the walls of a building have dissolved into the depicted three-dimensional space. Wall frescoes were usually divided into three registers, with the bottom register depicting false masonry painted in the manner of the First Style, while a simple border was painted in the uppermost register. The central register, where the main scene unfolds, is the largest and the focal point of the painting. This space was an architectural zone that became the main component of Second-Style painting. Typically, paintings that relied on near-perfect linear perspective to depict architectural expanses and landscapes that were painted on a human scale. The desired effect was to make the viewer felt as if, while in the room, he or she was physically transported to these spaces.

Detail from Villa of P. Fannius Synistor

Detail of an architectural vista from a second style wall painting. Villa of P. Fannius Synistor, Boscoreale, Italy. c. 50-40 BCE.

Villa of Livia

As the style evolved, the top and bottom registers became less important. Architectural scenes grew to incorporate the entire room such as at the Villa of the Mysteries and the Villa of Livia. In the case of the Villa of Livia, architectural vistas are replaced with a natural landscape that completely surrounds the room. The painting mimics the natural landscape outside the villa, depicting identifiable trees, flowers, and birds. Light filters naturally through the trees, which appear to bend in a slight breeze. Naturalistic elements like this, along with the flight of the birds and other details, help transport the occupant in the room into an outdoor setting.

Villa of Livia

Second style garden vista from the Villa of Livia, Primaporta, Italy. Late first century BCE.

Villa of the Mysteries

At the Villa of the Mysteries, just outside of Pompeii, a fantastic scene filled with life-size figures depicts a ritual element from a Dionysian mystery cult. In this Second-Style example, architectural elements play a small role in creating the illusion of ritual space. The people and activity in the scene are the main focus. The architecture present is mainly piers or wall panels that divide the main scene into separate segments. The figures appear life-size, which brings them into the space of the room.

Villa of the Mysteries

One wall on the ritual scene depicted at the Villa of Mysteries. Pompeii, Italy. c. 60-50 BCE.

The scene wraps around the room, depicting what may be a rite of marriage. A woman is seen preparing her hair. She is surrounded by other women and cherubs while a figure, identified as Dionysus, waits. The ritual may reenact the marriage between Dionysus and Ariadne, the daughter of King Minos. All the figures, except for Dionysus and one small boy, are female. The figures also appear to interact with one other from across the room. On the two walls in one corner, a woman reacts in terror to Dionysus and the mask over his head. On the opposite corner, a cherub appears to be whipping a woman on the adjoining wall. While the cult aspects of the ritual are unknown, the fresco demonstrates the ingenuity and inventiveness of Roman painters.

Third Style

Third-Style Pompeiian painting developed during the last decades of the first century BCE. It was popular from 20 BCE until the middle of the first century CE. During this period, wall painting began to develop a more fantastical personality. Instead of attempting to dissolve the wall, the Third Style acknowledges the wall through flat, monochromatic expanses painted with small central motifs that look like a hung painting. The architecture painted in Third-Style scenes is often logically impossible. The wall is frequently divided into three to five vertical zones by narrow, spindly columns and decorated with painted foliage, candelabra, birds, animals, and figurines. Often these creatures and people were derived from Egyptian motifs, resulting from a contemporary Roman fascination with Egypt known as Egyptomania, following the defeat of Cleopatra at Actium and the annexation of Egypt in 30 BCE.

Third Style Wall Painting

Detail of third style wall painting from the Villa of Agrippa Postumus. Boscotrecase, Italy. c. 10 BCE. Fresco.

Fourth Style

The Pompeian Fourth Style became popular around the middle of the first century CE. While considered less ornate than the Third Style, the Fourth Style is more complex and draws on elements from each of the three previous styles. In this style, masonry details of the First Style reappear on bottom registers, and architectural vistas of the Second Style are once more fashionable, although infinitely more complex than their Second-Style predecessors. Fantastical details, Egyptian motifs, and ornamental garlands from the Third Style continued into the Fourth Style. Large pictures, connected to each other by a program or theme, dominated each wall, as those in the House of the Vettii.

House of the Vettii

Many rooms in the House of the Vettii are lavishly painted. Each triclinium is themed and painted in the Fourth Style. Each panel in the room follows the room's theme, providing visual entertainment and a narrative during dining. The Ixion Room, for instance, is a model of Fourth-Style wall painting. Within each red panel is a scene depicting myths where the main character commits a major slight. One panel is dedicated to Ixion, who refused to pay a dowry and murdered his father-in-law. He also lusted after Zeus's wife, betraying the relationship between guest and host. Another panel depicts Daedalus presenting a wooden cow to Pasiphaë, wife of King Minos, so she could relieve her lust for a white bull. From this union, Pasiphaë birthed the Minotaur, a half-man, half-bull monster. Another Fourth-Style triclinium depicts scenes from the lives of Hercules and Theseus.

Daedelaus and Pasiphaë

Daedalus presents Pasiphaë with a wooden heifer.

Fourth Style

Detail of a fourth style wall in the Ixion Room of the House of the Vettii. Fresco. Pompeii, Italy. c. 70-79 CE.

House of the Tragic Poet

The atrium of the House of the Tragic Poet includes a series of paintings depicting scenes from the Trojan War. The panels on the walls depict scenes that appear to be interrelated. As in the panels that decorate the House of the Vettii, the subject matter in the paintings in the House of the Tragic Poet are interrelated based on a common theme. Scholars believe themes were carefully crafted not only to relate stories, but also to depict the virtues of the house's owner.

Two panels on the south wall relate the beginnings of the Trojan War. One panel is of Zeus and Hera on Mount Ida. Another, badly damaged, appears to be a scene of the Judgment of Paris. These panels relate the beginnings of the Trojan War while portraying womanly ideals. Two pairs of scenes, set across from each other, depict different, interrelated themes. The abduction of women is one theme visible in one image of Helen with Paris leaving for Troy. Another image portrays the abduction of Amphitrite by Poseidon. In both cases, a man abducts a woman. The other two scenes deal with the argument between Achilles and Agamemnon, which begins the story of the Illiad. Of these two scenes, one depicts Achilles with Agamemnon, while the other depicts Achilles returning Briseis, his lover and captive, to his commander, Agamemnon. A final image, found in the peristyle, depicts the Sacrifice of Iphigenia. All of these paintings are related to one another through themes such as marriage, womanly virtue, and the Trojan War.

The Sacrifice of Iphigenia

House of the Tragic Poet, Pompeii, Italy. c. 60-65 CE.

Riot at the Amphitheatre

While the above examples of Fourth-Style painting depict scenes from mythology, at least one contemporary scene is represented in a surviving fresco. In 59 CE, a riot broke out between the citizens of Pompeii and the citizens of nearby Nuceria during a gladiatorial event. The brawl in the amphitheater resulted in serious injuries between both parties and the banning of all gladiatorial events for ten years. A fresco from Pompeii that depicts the event has also survived. The fresco depicts the Pompeiian amphitheatre, with its distinctive exterior staircase, as well as an awning, the velarium. It also depicts the riot occurring both inside the arena and on the grounds surrounding the amphitheatre.

Depiction of a riot at the amphitheatre at Pompeii, 59 CE.

Pompeii, Italy. c.60-79 CE.