Etruscan temples were adapted from Greek-style temples to create a new Etruscan style, which, in turn would later influence Roman temple design. The temple was only one part of the templum, the defined sacred space that including the building, altar and other sacred ground, springs, and buildings. As in Greece and Rome, the altar used for sacrifice and ritual ceremonies was located outside the temple.

Today only the foundations and terra cotta decorations of Etruscan temples remain, since the temples themselves were primarily built of wood and mud brick that eroded and degraded over time. The Etruscans used stone or tufa as the foundation of their temples. Tufa is a local volcanic stone that is soft, easy to carve, and hardens when exposed to air. The superstructure of the temple was built from wood and mud brick. Stucco or plaster covered the walls and was either burnished to a shine or painted. Terra cotta roof tiles protected the organic material and increased the longevity and integrity of the building.

Foundation of an Etruscan temple at Orvieto.

The central stairway highlights the frontality of the temple that once stood at this site.

Archaeology and a written accounts by the Roman architect Vitruvius during the late first century BCE allows us to reconstruct a basic model of a typical Etruscan temple. Etruscan temples were usually frontal, axial, and built on a high podium with a single central staircase that allowed access to the cella (or cellas). Two rows of prostyle columns stood on the front of the temple's portico. The columns were of the Tuscan order, a derivative of the Doric order consisting of a simple shaft on a base with a simple capital. A scale model of the Portonaccio Sanctuary of Minerva suggests that the bases and capitals of its columns were painted with alternating dark- and light-valued hues. While most portico columns were made of wood, there is evidence that some were made of stone, as at Veii. They were tall and widely spaced across a deep porch, aligning with the walls of the cellas.

Model of Portonaccio Sanctuary of Minerva

c. 510 BCE. Veii.

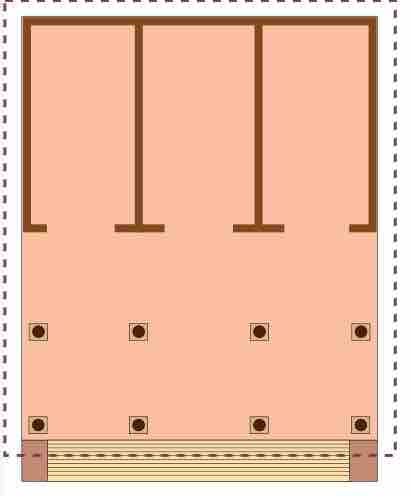

Etruscans often, although not always, worshiped multiple gods in a single temple. In such cases, each god received its own cella, which housed its cult statue. Often the three-cella temple would be dedicated to the principal gods of the Etruscan pantheon -- Tinia, Uni, and Menrva (comparable to the Roman gods Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva). The wooden roof had a low pitch and was covered by a protective layer of terra cotta tiles. Eaves with wide overhangs helped to protect the organic material from rain.

Ground Plan of an Etruscan Temple

Ground plan of an Etruscan temple

Many aspects of Vitruvius's description fit what archaeologists can demonstrate. However deviations did exist. It is clear that Etruscan temples could take a number of forms and also varied over the 400-year period during which they were being made. Nevertheless, Vitruvius remains the inevitable starting point for a description and a contrast of Etruscan temples with their Greek and Roman equivalents.

Antefix

To further protect the roof beams from rain, insects, and birds, the end of each row of roof tiles was capped by an ornament known as an antefix. Antefixes also lined the area of the façade that corresponds to the top of the frieze and bottom of the pediment on a Greek temple. These flat ornaments were usually made of terra cotta from a mold, and were sometimes made of stone. The antefixes were brightly painted and often depicted images female and male faces or simple geometric designs. The male faces were often representations of the Etruscan equivalent to Dionysus or his followers, including Silenus or fauns. Although some antefixes depicted women, many of the female figures were representations of Gorgons, such as Medusa. The Gorgon-faced antefixes often showed a wide-eyed, circular face surrounded by either wings or snakes. The Gorgon and Dionysiac antefixes served apotropaic functions, intended to ward off evil and protect the temple site.

Antefix with the head of a Gorgon

Terra cotta. c. 6th-5th century BCE.

Antefix with Silenus Face

Terra cotta

Akroteria

For much of their history, the Etruscans did not decorate their temples in the Greek manner with friezes or pedimental sculptures. Instead, they placed terra cotta statues called akroteria along the roof's ridge pool and on the peaks and edges of the pediment. These akroteria figures were generally built slightly larger than life-sized and were connected thematically. The Apulu of Veii is one example of an akroteria and is part of a sculptural group that depicted the story of Herakles and the Ceryneaian Hind.