Tombs and necropoleis are among the most excavated and studied parts of Etruscan culture. Scholars learn about Etruscan society and culture from the study of Etruscan funerary practice. Burial urns and sarcophagi, both large and small, were used to hold the cremated remains of the dead. Early forms of burial include the burial of ashes with grave goods in funerary urns and small ceramic huts . Later, in the seventh century BCE, the Etruscans began burying their dead in subterranean family tombs. The necropoleis at Cerveteri and Tarquinia are the most well known for their tumuli and frescoed tombs.

Hut Urn

Etruscan cinerary hut urn with a door. Impasto. 8th century BCE.

The grave goods found in these tombs point to the Etruscan belief in an afterlife that required the same types of goods and materials as in the world of the living. Many examples of Greek pottery have been recovered from Etruscan tombs. These vessels, along with other foreign goods, demonstrate the extent of the Etruscan trade network. Painted scenes of frivolity, celebration, hunting, and religious practice tell the viewer about Etruscan daily life, ritual, their belief about the afterlife, and their social norms. The imagery and grave goods found in Etruscan tombs help inform the modern day viewer about the nature of Etruscan society.

Banditaccia Necropolis at Cerveteri

The tombs of the Banditaccia Necropolis outside Cerveteri were carved into large, circular mounds known as tumuli. Each tumulus was the burial site for a single family, and one to four underground tombs were cut into the round tumulus. Each tomb often represented a separate generation. The tombs were carved with a long, narrow entranceway known as a dromos, which opened into a single or multi-room chamber. The decorative style of each chamber and tomb varied with the period and the family's wealth. The wealthier the family, the more intricately carved and decorated the tomb.

Banditaccia Necropolis

Banditaccia Necropolis. 7th-2nd c. BCE. Cerveteri, Italy.

Most tombs assumed the shape and style of Etruscan homes. The ceilings were often carved to represent wood roof beams. Thatching and decorative columns were often added to a room. The entrances and the individual rooms inside were often framed by doorways carved in a typical design. Piers are topped with capitals carved in a stylized motif that resembles those from Corinthian columns. Each room contained beds or niches, sometimes with a carved tufa pillow, for the deposition of the body.

The most recent tombs in Banditaccia date from the third century BCE. Some of are marked by external boundary posts called cippi (singular cippus). Cylindrical cippi outside a tomb indicate that its occupants are male, while those in the form of small houses indicate female occupants.

Cippi outside a tomb in the Banditaccia necropolis

The phallic shape of these cippi indisate that men are interred in the tomb.

The Tomb of the Reliefs is one of the most well known, largest, and richly decorated tombs from the Banditaccia Necropolis. This tomb is named for the numerous tufa reliefs of everyday objects inside. The walls and piers are covered in carved and painted reliefs of everyday objects including rope, drinking cups, pitches, mirrors, knives, helmets, and shields. Not even companion animals were forgotten in the afterlife. A stretching cat adorns the base of the column on the left, while one in mid-motion (stalking prey?) adorns the base of the column on the right. Elsewhere in the tomb, mythological subject matter appears. In the center is a depiction of the three headed dog, Cerberus, the guardian to the underworld.

Tomb of the Reliefs

Interior of the Tomb of the Reliefs. Carved tufa and paint. 3rd c. BCE. Banditaccia Necropolis, Cerveteri, Italy.

Monterozzi Necropolis at Tarquinia

The tombs of the Monterozzi Necropolis outside of Tarquinia are also subterranean burial chambers. The graves from the necropolis date from the seventh century BCE until the first century BCE. The tombs here are similar to the underground, tufa cut tombs of Cerveteri that were accessed through a dromos.

The Tomb of the Augurs (530-520 BCE) was one of the first in Tarquinia to have figurative decorations on all four walls of its main or only chamber. Its name derives from a possible misinterpretation of two figures on the rear wall. This tomb is also the first to depict Etruscan funerary rites and funerary games in addition to mythological scenes, which were already established in traditional funerary art.

A fresco depicting a door flanked by two men appears on the rear wall of the Tomb of the Augurs. Scholars have come to different conclusions as to the significance of the door. Some interpret it as a representational illustration of the door to the tomb. Others argue that it is a symbolic door or portal to the underworld that acts as a barrier between the kingdom of the living and the kingdom of the dead. The two men each extend one arm toward the door and places the other hand places the hand against his forehead in a gesture of salutation and mourning. Past interpretations identify the men as augurs. However, the word Apastanasar, which appears on the wall next to the man on the right, contains the root of apa which means father. This leads scholars to conclude that they two men are more likely relatives of the deceased.

“Augurs"

Interior rear wall of the Tomb of the Augurs. Fresco. c. 530 BCE. Monterozzi Necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy.

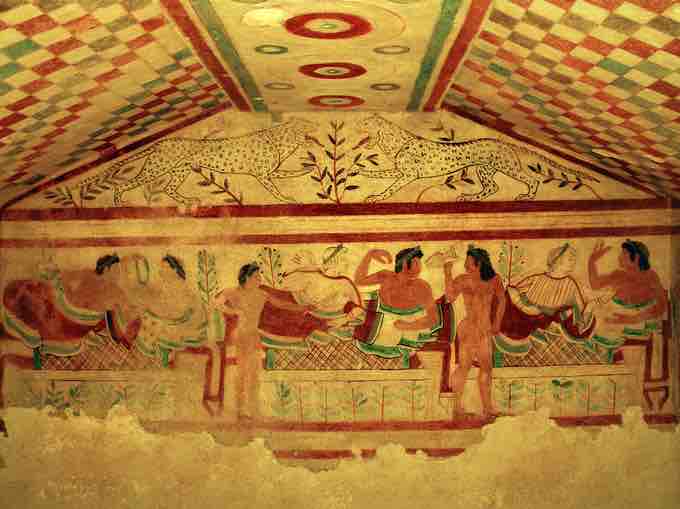

The Tomb of the Leopards (early fifth century BCE), which consists of a single room, is one of the best known tombs of Tarquinia. The Banqueting Scene, the most famous mural in the tomb, is divided into two panels: the pediment and the frieze. The pediment depicts two white leopards in a heraldic composition. This depiction is reminiscent of the leopards from the pediment of the Temple of Artemis at Corfu. The felines are used for their apotropaic, protective features. Below the pediment is the main scene depicted on a central frieze that wraps around the room. This image depicts men and women with servants at a symposium. The scenes are festive and joyous. Men and women are distinguished respectively with dark and light skin tones. The mere presence of women in the Banqueting Scene is unique for its time, suggesting a gender-inclusive culture. However, the women's assumption of the same positions as their male counterparts and their apparently active participation in the festivities suggest a level of gender equality unseen among the Greeks or, later, the Romans.

The Banqueting Scene

Interior back wall of the Tomb of the Leopards. Fresco. c. 480-470 BCE.

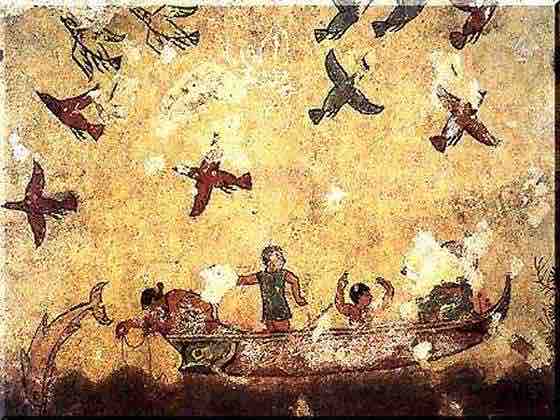

The Tomb of Hunting and Fishing consists of two rooms. The frescos in the first room are badly damaged but appear to depict Etruscans dancing outside. Two trees frame the doorway into the second room. This room gives the tomb its name, as it depicts a scene of men hunting and fishing. Men in boats are fishing in a sea populated by fish and dolphins. On a rock outcropping in the water, one man prepares to dive, while another climbs to the top. Meanwhile, another man aims a slingshot at the birds that flock overhead. This scene depicts Etruscans' relationship with nature and the importance of hunting and fishing in Etruscan society.

Tomb of Hunting and Fishing

Interior back wall from the Tomb of Hunting and Fishing. Fresco. c. 530-520 BCE. Monterozzi Necropolis, Tarquinia, Italy.