Overview: Mughal Painting

Mughal painting is a style of South Asian miniature painting that developed in the courts of the Mughal Emperors between the 16th and 19th centuries. It emerged from the Persian miniature painting tradition with additional Hindu, Buddhist, and Jain influences. Mughal painting usually took the form of book illustrations or single sheets preserved in albums. There are four periods commonly associate with Mughal art, each named for the emperor under whom the art form developed: the Akbar Period, the Jahangir Period, the Shah Jahan Period, and the Aurangzeb Period.

Origins

Mughal painting was an amalgam of Ilkhanate Persian and Indian techniques and ideas. Under the Delhi Sultanate, the early 16th century had been a period of artistic inventiveness during which a previously formal and abstract style had begun to make way for a more vigorous and human mode of expression. After Mughal victory over the Delhi Sultanate in 1526, the tradition of miniature painting in India further abandoned the high abstraction of the Persian style and began to adopt a more realistic style of portraiture and of drawing plants and animals.

The Akbar Period (1556–1605)

It was under the reign of Akbar the Great (1556–1605) that Mughal painting came into its own. Trained in painting in his youth by the Persian master 'Abd al-Samad, Akbar was responsible for setting up the first atelier of court painters, which he staffed with artists from all parts of India whose work he took a keen interest in. This atelier was chiefly responsible for illustrating books on a variety of subjects: histories, romances, poetry, legends, and fables of both Persian and Indian origin.

One of the greatest achievements of Mughal painting under Akbar may be found in the stupendously illustrated Hamzanama or Dastan-e-Amir Hamza, a narration of the legendary exploits of Amir Hamza, the uncle of Muhammad. The size of this manuscript was unprecedented: spanning 14 volumes, it originally contained 1400 illustrations of an unusually large size (approx. 25" x 16"). Only about 200 of these original illustrations survive today. It took 14 years (1562–1577) and over a hundred men to complete. The paintings mark a significant departure from the Persian style in their bent towards naturalism, vigorous portrayal of movement and emotion, and bold color. Each form is individually modeled, and the figures are interrelated in closely unified compositions. Depth is indicated by a preference for diagonals.

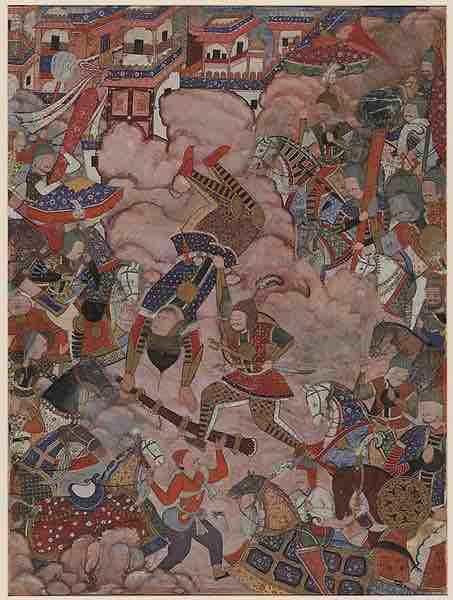

The Battle of Mazandaran

This painting is number 38 in the 7th volume of the Hamzanama. It depicts a battle scene in which the protagonists, Khwajah 'Umar and Hamzah, and their armies engage in fierce battle. Originally clearly depicted, the faces were erased by iconoclasts and then repainted in more recent times. Only the face of the groom wearing an orange turban in the center of the left edge has been left untouched.

Methods and Techniques Under Akbar

The methods most commonly used by Mughal painters were first developed in Akbar's great atelier. Illustrations were usually executed by groups of painters, including a colorist (who was responsible for the actual painting) and specialists in portraiture and the mixing of colors. Leading this group was the designer, an artist of the highest caliber, who formulated the composition and sketched the outline into the spaces in the manuscripts designated by the calligraphers for illustration. A thin wash of white was then applied, through which the outline remained visible. The colors were then applied in several thin layers and rubbed down with an agate burnisher to produce a glowing, enamel-like finish. The colors used were mostly mineral and sometimes vegetable dyes, and the fine brushes were made from squirrel's tail or camel hair.

The Jahangir Period (1605–1627)

Like his father Akbar, the emperor Jahangir showed a keen interest in painting and maintained his own atelier. The tradition of illustrating books assumed secondary importance to portraiture during Jahangir's reign because of the emperor's own preference for portraits. Among the finest works of his reign are elaborate court scenes depicting him surrounded by his courtiers. These are large scale exercises in portraiture, and the likeness of each figure is produced faithfully. The composition lacks the vigor, movement, and vivid color characterized by the works of Akbar's reign; the figures are more formally ordered, the colors soft and harmonious, and the brushwork particularly fine. Mughal paintings during Jahangir's reign also boast magnificent floral and geometric borders.

European Influence

Jahangir was also deeply influenced by European painting, having come into contact with the English crown and received gifts of oil paintings from England. He encouraged his atelier to emulate the single point perspective favored by European painters, unlike the flattened, multi-layered style traditionally used in miniature painting. These influences are evident in the illustrations of the Jahangirnama, a biographical account of Jahangir's own life. In addition to portraits, many works included plant and animal studies and became part of lavishly finished albums. Most illuminated manuscripts were created by a single painter.

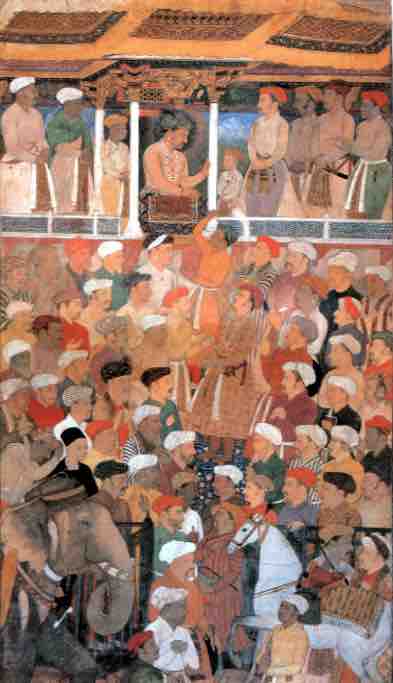

Jahangir in Darbar

Illustration of a court scene from the Jahangirnama, c. 1620. Jahangir makes a public appearance on a balcony as a large group of courtiers stand below.

The Shah Jahan Period (1628–1658)

While the artistic focus of the Mughal court shifted primarily to architecture under Shah Jahan, painting continued to flourish. The style became notably more rigid, and portraits resembled abstract effigies. Paintings of this period were particularly opulent, as the colors used became jewel-like in their brilliance. Popular themes included musical parties, lovers in terraces and gardens—sometimes locked in intimate embraces—and ascetics and holy men.

The Aurangzeb and Late Mughal Period (1658–1809)

The emperor Aurangzeb (1658–1707) did not encourage Mughal painting, and only a few portraits survive from his court. Most of these were accomplished in the cold, abstract style of Shah Jahan. While the art form had gathered sufficient momentum to invite patronage in other courts—Muslim, Hindu, and Sikh alike—the absence of strong imperial backing ushered in a decline of the art form. A brief revival occurred during the reign of Muhammad Shah (1719–1748), who was passionately devoted to the arts, but this was only temporary. Mughal painting essentially came to an end during the reign of Shah Alam II (1759–1806), and the artists of his disintegrated court contented themselves with copying masterpieces of the past.