Overview

Romanesque art refers to the art of Europe from the late 10th century to the rise of the Gothic style in the 13th century or later, depending on region. The term "Romanesque" was invented by 19th century art historians to first refer specifically to architecture of the time period, which retained many basic features of Roman architectural style—most notably semi-circular arches—but had also developed many very different and regional characteristics. In Southern France, Spain, and Italy, there had been architectural continuity with the Late Antique period, but the Romanesque style was the first style to spread across the whole of Catholic Europe, making it the first pan-European style since Imperial Roman Architecture. Romanesque art was also greatly influenced by Byzantine art, especially in painting, and by the anti-classical energy of the decoration of the Insular art of the British Isles. From these elements was forged a highly innovative and coherent style.

Architecture

Combining features of Roman and Byzantine buildings along with other local traditions, Romanesque architecture is known by its massive quality, thick walls, round arches, sturdy piers, groin vaults, large towers, and decorative arcades. Each building has clearly defined forms. They are frequently of very regular, symmetrical plan; the overall appearance is one of simplicity when compared with the Gothic buildings that were to follow. The style can be identified across Europe, despite regionally varying characteristics and materials.

Maria Laach Abbey, Germany

This abbey, founded in 1093, is an example of Romanesque architecture.

Painting

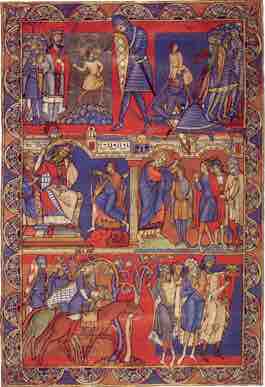

Aside from Romanesque architecture, the art of the period was characterized by a vigorous style in both painting and sculpture. Painting continued to follow Byzantine iconographic models for the most common subjects in churches. Christ in Majesty, the Last Judgement and scenes from the Life of Christ remained among the most popular depictions. In illuminated manuscripts, where the most lavishly decorated manuscripts of the period included bibles or psalters, more originality could be seen, as new scenes needed to be depicted. Colors, which we can now see in their original brightness only in stained glass and well-preserved manuscripts, tended to be very striking, depending heavily on intensely saturated primary colors. It was in this period that stained glass came to be widely used, although there are few surviving examples.

Pictorial compositions usually had little depth and needed to be flexible to squeeze themselves into the shapes of historiated initials, column capitals, and church tympanums. The tension between a tightly enclosing frame and the composition which sometimes escapes its designated space is a recurrent theme in Romanesque art. Figures often varied in size in relation to their importance, and landscape backgrounds, if attempted at all, were closer to abstract decorations than realism—as in the trees in the "Morgan Leaf". This abstraction could also be seen in the elongation of human forms, which were often contorted to fit the shape of the space provided and at times appeared to be floating in space. Depictions of the human form tended to focus on linear details with emphasis on drapery folds and hair.

The "Morgan Leaf. "

The "Morgan Leaf,"detached from the illuminated Winchester Bible of 1160-75. Scenes from the life of David.

Sculpture

Sculpture of the time also exhibited a vigorous style, as seen in the carved capitals of columns, which often depicted complete scenes consisting of several figures. Precious objects sculpted in metal, enamel, and ivory, such as reliquaries, also had very high status in this period. The large wooden crucifix was a German innovation at the start of the period, as were free-standing statues of the enthroned Madonna; however, the high relief carvings of architectural elements were the signature work in the sculptural mode of the period.

In a significant innovation of the period, the tympanums of important church portals were carved with monumental schemes, often again depicting Christ in Majesty or the Last Judgement but treated with more freedom than painted versions. These portal sculptures were meant to both intimidate and educate the viewer. As there were no equivalent Byzantine models, Romanesque sculptors felt free to expand rather than merely mimic in their treatment of tympanums.

The portal of Saint-Pierre, Moissac

The portal of Saint-Pierre, Moissac Abbey, Moissac, France.