Overview: The Southern School and Literati Painting

Under the Ming Dynasty, Chinese culture bloomed. Narrative painting, with a wider color range and a much busier composition than the previous paintings of the Song Dynasty, was immensely popular during the time.

The Southern School of Chinese painting, often known as "literati painting," is a term used to denote art and artists that stand in opposition to the formal Northern School of painting. Where formal and professional painters were classified as Northern School, scholar-bureaucrats, who had either retired from the professional world or who had never been a part of it, constituted the Southern School.

History

Never a formal school of art in the sense of artists training under a single master in a single studio, the Southern School is more of an umbrella term spanning a great breadth across both geography and chronology. The literati lifestyle and attitude, as well as the associated style of painting, can be said to go back to early periods of Chinese history. However, the coining of the term "Southern School" is said to have been made by the scholar-artist Dong Qichang (1555–1636), who borrowed the concept from Ch'an (Zen) Buddhism, which also has Northern and Southern Schools.

The Literati Style and Artists

Generally, Southern School painters worked in monochrome ink, focused on expressive brushstrokes, and used a somewhat more impressionistic approach than the Northern School's formal attention to detail, use of color, and highly refined traditional modes and methods. The stereotypical literati painter lived in retirement either in the mountains or other rural areas, not entirely isolated but immersed in natural beauty and far from mundane concerns. These artists tended to be lovers of culture, enjoying and taking part in all Four Arts of the Chinese Scholar (painting, calligraphy, music, and games of skill and strategy) as touted by Confucianism. Many artists would combine these elements into their work and would gather with one another to share their interests.

Artwork by Wen Zhengming, a leading Ming Dynasty painter

Wen Zhengming often chose painting subjects of great simplicity, like a single tree or rock. His work often brings about a feeling of strength through isolation, which often reflected his discontent with official life.

Literati paintings are most commonly of landscapes, often of the shanshui ("mountain water") genre. Many feature scholars in retirement or travelers admiring the scenery or immersed in culture. Figures are often depicted carrying or playing guqin (a plucked seven-string Chinese musical instrument of the zither family) and residing in quite isolated mountain hermitages. Calligraphic inscriptions, either of classical poems or ones composed by a contemporary literati (typically the painter or a friend), are also quite common. While this sort of landscape with certain features and elements is the standard stereotypical Southern School painting, the genre actually varied quite widely in rejecting the formal strictures of the Northern School. The painters sought the freedom to experiment with subjects and styles.

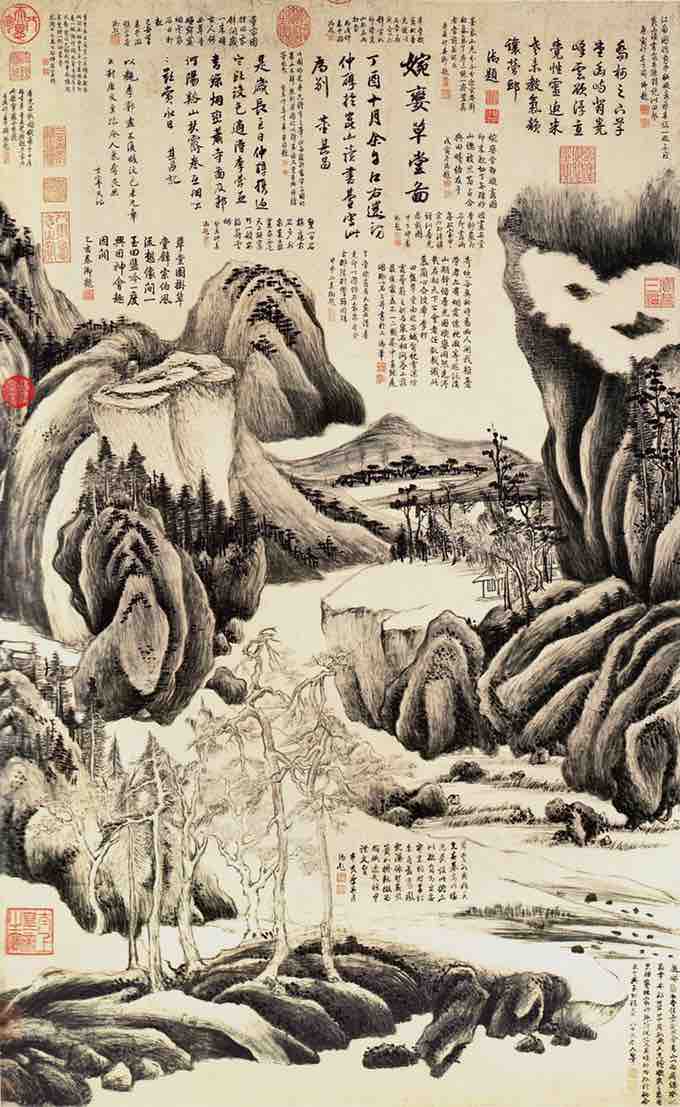

Dong Qichang, Wanluan Thatched Hall (1597): hanging scroll, ink and light colors on paper

Dong Qichang created landscapes with intentionally distorted spatial features.

Like other traditions in Chinese art, the early Southern style soon acquired a classic status and was often copied and imitated, with later painters sometimes producing sets of paintings each in the style of a different classic artist. Though greatly affected by the confrontation with Western painting from the 18th century on, the style continued to be practiced until at least the 20th century.

Shen Zhou, Lofty Mt.Lu (蘆) Hanging scroll, ink and light colors on paper (1467)

Shen Zhou paintings reveal a disciplined obedience to the styles of the Yuan Dynasty, to China's history, and to the orthodox Confucianism that he embodied in his filial life.