The Mesopotamians regarded "the craft of building" as a divine gift taught to men by the gods, and architecture flourished in the region. A paucity of stone in the region made sun baked bricks and clay the building material of choice. Babylonian architecture featured pilasters and columns, as well as frescoes and enameled tiles. Assyrian architects were strongly influenced by the Babylonian style, but used stone as well as brick in their palaces, which were lined with sculptured and colored slabs of stone instead of being painted. Existing ruins point to load-bearing architecture as the dominant form of building. However, the invention of the round arch in the general area of Mesopotamia influenced the construction of structures like the Ishtar Gate in the sixth century BCE.

Domestic Architecture

Mesopotamian families were responsible for the construction of their own houses. While mud bricks and wooden doors comprised the dominant building materials, reeds were also used in construction. Because houses were load-bearing, doorways were often the only openings. Sumerian culture observed a rigid division between the public sphere and the private sphere, a norm that resulted in a lack of direct view from the street into the home. The sizes of individual houses varied, but the general design consisted of smaller rooms organized around a large central room. To provide a natural cooling effect, courtyards became a common feature in the Ubaid period and persist into the domestic architecture of present-day Iraq.

Ziggurats

One of the most remarkable achievements of Mesopotamian architecture was the development of the ziggurat, a massive structure taking the form of a terraced step pyramid of successively receding stories or levels, with a shrine or temple at the summit. Like pyramids, ziggurats were built by stacking and piling. Ziggurats were not places of worship for the general public. Rather, only priests or other authorized religious officials were allowed inside to tend to cult statues and make offerings. The first surviving ziggurats date to the Sumerian culture in the fourth millennium BCE, but they continued to be a popular architectural form in the late third and early second millennium BCE as well .

Chogha Zanbil ziggurat

The Chogha Zanbil ziggurat was built in 1250 BC by Untash-Napirisha, the king of Elam, to honor the Elamite god Inshushinak.

The image below is an artist's reconstruction of how ziggurats might have looked in their heyday. Human figures appear to illustrate the massive scale of these structures. This impressive height and width would not have been possible without the use of ramps and pulleys.

An artist's reconstruction of a ziggurat

Like most Mesopotamian architecture, ziggurats were composed of sun-baked bricks, which were less durable than their oven-baked counterparts. Thus, buildings had to be reconstructed on a regular basis, often on the foundations of recently deteriorated structures, which caused cities to become increasingly elevated. Sun-baked bricks remained the dominant building material through the Babylonian and early Assyrian empires.

Political Architecture

The exteriors of public structures like temples and palaces featured decorative elements such as bright paint, gold, leaf, and enameling. Some elements, such as colored stones and terra cotta panels, served a twofold purpose of decoration and structural support, which strengthened the buildings and delayed their deterioration.

Between the thirteenth and tenth centuries BCE, the Assyrians replaced sun-baked bricks with more durable stone and masonry. Colored stone and bas reliefs replaced paint as decoration. Art produced under the reigns of Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 BCE), Sargon II (722-705 BCE), and Ashurbanipal (668-627 BCE) inform us that reliefs evolved from simple and vibrant to naturalistic and restrained over this time span.

From the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2350 BCE) to the Assyrian Empire (25th century-612 BCE), palaces grew in size and complexity. However, even early palaces were very large and ornately decorated to distinguish themselves from domestic architecture. Because palaces housed the royal family and everyone who attended to them, palaces were often arranged like small cities, with temples and sanctuaries, as well as locations to inter the dead. As with private homes, courtyards were important features of palaces for both utilitarian and ceremonial purposes.

By the time of the Assyrian empire, palaces were decorated with narrative reliefs on the walls and outfitted with their own gates. The gates of the Palace of Dur-Sharrukin, occupied by Sargon II, featured monumental alto reliefs of a mythological guardian figure called a lamassu (also known as a shedu), which had the head of a human, the body of a bull or lion, and enormous wings. Lamassu figure in the visual art and literature from most of the ancient Mesopotamian world, going as far back as ancient Sumer (settled c. 5500 BCE) and standing guard at the palace of Persepolis (550-330 BCE).

Lamassu

This is only one example of how a lamassu would appear in Mesopotamian art. Other sculptures wear conical caps, face the front, or have the bodies of lions. In literature, some lamassu assumed female form.

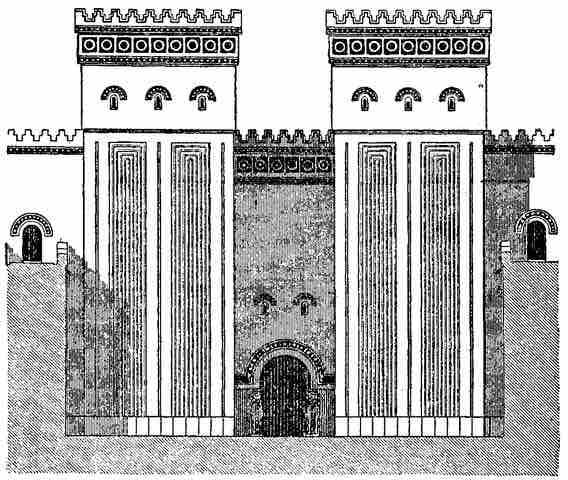

Although the Romans often receive credit for the round arch, this structural system actually originated during ancient Mesopotamian times. Where typical load-bearing walls are not strong enough to have many windows or doorways, round arches absorb more pressure, allowing for larger openings and improved airflow. The reconstruction of Dur-Sharrukin shows that the round arch was being used as entryways by the eighth century BCE.

Palace of Dur-Sharrukin

Round arches can be found in the central portal, as well as in each window on the right and left.

Perhaps the best known surviving example of a round arch is in the Ishtar Gate, which was part of the Processional Way in the city of Babylon. The gate, now in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin, was lavishly decorated with lapis lazuli complemented by blue glazed brick. Elsewhere on the gate and its connecting walls were painted floral motifs and bas reliefs of animals that were sacred to Ishtar, the goddess of fertility and war.

Ishtar Gate (c. 575 BCE)

The reconstruction of the Ishtar Gate in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

The photograph above shows the immense scale of the gate. The photograph below shows the detail of a relief of a bull from the gate’s wall.

Detail of bull relief on Ishtar Gate

An aurochs, or bull, above a flower ribbon.