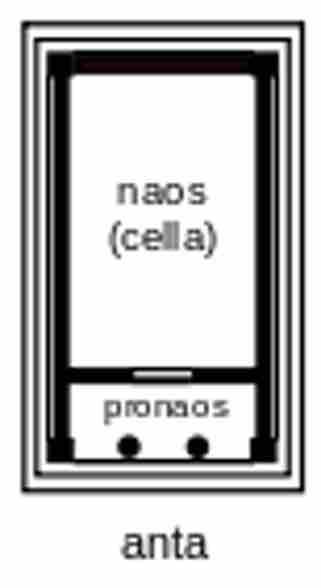

The basic principles for the development of Greek temple architecture have their roots between the tenth and seventh centuries BCE. In its simplest form as a naos or cella, the temple was a simple rectangular shrine with protruding side walls (antae), forming a small porch. By adding columns to this small basic structure, the Greeks triggered the development and variety of their temple architecture.

Anta schematic

Early anta-planned temples consisted of a portico (pronaos) and an inner chamber (naos/cella) atop a simple platform. Two columns marked the entrance to the inner chamber.

The building of stone temples first began during the Oriental period. Earlier temples were made from wood and other perishable materials and used terra cotta revetments in the form of rectangular and circular panels. With the introduction of stone as a building material, revetments became unnecessary and were replaced by sculptural ornamentation. These temples derive their structure from Minoan and Mycenaean architectural designs. Minoan shrines, as seen at Knossos, were tripartite shrines fronted by three columns, while the plan of the Mycenaean king's chamber (or megaron) was appropriated for use by the gods. Oriental Greek stone temples were fronted by three columns and one entrance which lead into a single room chamber (cella), where the cult statue would be placed. The temple cella was reserved for the cult statue, while cult rituals (often sacrifices) took place outside in front of the temple and usually around an altar.

Temple A at Prinias (c. 650-600 BCE) on the island of Crete is the oldest known Greek temple decorated with sculpture. Its plan was similar to the anta design with a third column in the center in front of the doorway. One step spanning the width of the façade led to the pronaos. The columns were very simple rectangular (as opposed to cylindrical) blocks with very thin bases and capitals. Unlike Minoan columns, the shafts of the columns of Temple A did not taper; rather, their width remained constant for the entire length.

On the entablature, the frieze of the façade consisted of a series of reliefs depicting a procession of riders on horseback with little variation. The scale of the horses dwarfs that of their riders. Each horse stands in profile, while each rider faces the viewer with his sword raised and his shield seemingly connecting his head to his legs. Although their shields cover most of their bodies, the seemingly bare state of their legs imply that the riders might be nude, as was typical for the male body in art. Each rider has a stylized nose, eyes, and eyebrows and wears a helmet. Like free-standing sculptures of the time, the hairstyle of the riders is plaited in a somewhat Egyptian style. A meander runs atop the reliefs. The current cracked condition of the frieze is a likely indicator that it was assembled in a piecemeal fashion, as opposed to being carved as a singular entablature. Atop the entablature sat sculptures of two winged female creatures resembling the sphinx or the lamassu of the ancient Assyrian and Babylonian cultures.

Temple A portico frieze

Marble. Prinias, Crete. c. 650-600 BCE.

Behind the façade of Temple A sat a doorway with an intricately designed lintel. Its frieze consisted of six stylized panthers standing in high relief. This motif is typical of northern Syria. Unlike the horses on the façade frieze, each group of three panthers face each other with their heads turned toward the viewer. Between each group sits a plain rectangular recess, probably to mark the location of the central column that supported the lintel. Atop the frieze sit two stylized female sculptures in the round who face each other. One figure places her hands flatly on her lap, while the other holds her hands in a position to accommodate a cup or similar object. It is believed that these figures represent goddesses, although the identities of those goddesses remain disputed. Each sits in profile on a plain backless bench. The face of each figure has almond-shaped eyes and stylized eyebrows similar to those on Egyptian sculptures. Their hair is plaited and falls to either side of their shoulders. Like the free-standing sculptures of the Orientalizing period, each figure on the lintel of Temple A wears Egyptian-style headgear with geometric patterns and cloaks atop their geometrically patterned dresses, which are cinched at the waist. While their feet protrude from beneath their long skirts, the blocks that define the lower parts of their bodies provide no acknowledgement of the body beneath the clothing.

Lintel from Temple A.

Marble. Prinias, Crete. c. 650-600 BCE.