Hydrogenation

Did you know...

Arranging a Wikipedia selection for schools in the developing world without internet was an initiative by SOS Children. See http://www.soschildren.org/sponsor-a-child to find out about child sponsorship.

Hydrogenation is a class of chemical reactions which result in an addition of hydrogen (H2) usually to unsaturated organic compounds. The process constitutes the addition of hydrogen atoms to the double bonds of a molecule through the use of a catalyst. Hydrogen also adds to triple bonds if they are present. Typical substrates include alkenes, alkynes, ketones, nitriles, and imines. Most hydrogenations involve the direct addition of diatomic hydrogen (H2) but some involve the alternative sources of hydrogen, not H2: these processes are called transfer hydrogenations. The reverse reaction, removal of hydrogen, is called dehydrogenation. A reaction involving hydrogen and cleavage of a carbon-oxygen bond or carbon-nitrogen bond is called Hydrogenolysis. Hydrogenation differs from protonation or hydride addition (e.g. use of sodium borohydride): in hydrogenation, the products have the same charge as the reactants.

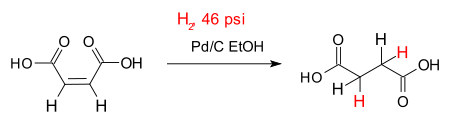

The classical example of a hydrogenation is the addition of hydrogen on unsaturated bonds between carbon atoms, converting alkenes to alkanes. A simple example is the hydrogenation of maleic acid to succinic acid depicted on the right. Numerous important applications are found in the petrochemical, pharmaceutical and food industries.

Health concerns associated with the hydrogenation of unsaturated fats to produce saturated fats and trans fats is an important aspect of current consumer awareness.

Process

Hydrogenation has three components:

- the unsaturated substrate,

- the hydrogen (or hydrogen source) and, invariably,

- a catalyst.

The largest scale technological uses of H2 are the hydrogenation and hydrogenolysis reactions associated with both heavy and fine chemicals industries. Hydrogenation is the addition of H2 to unsaturated organic compounds such as alkenes to give alkanes and aldehydes to give alcohols. Hydrogenation reactions require metal catalysts, often those composed of platinum or similar precious metals.

The addition of H2 to an alkene affords an alkane in the protypical reaction:

- RCH=CH2 + H2 → RCH2CH3 (R = alkyl, aryl)

An important characteristic of alkene and alkyne hydrogenations both homogeneous and heterogeneous is that hydrogen addition takes place with syn addition with hydrogen entering from the least hindered side.

Catalysts

With rare exception, no reaction below 480 °C occurs between H2 and organic compounds in the absence of metal catalysts. The catalyst simultaneously binds both the H2 and the unsaturated substrate and facilitates their union. Platinum group metals, particularly platinum, palladium, rhodium and ruthenium, are highly active catalysts. Highly active catalysts operate at lower temperatures and lower pressures of H2. Non-precious metal catalysts, especially those based on nickel (such as Raney nickel and Urushibara nickel) have also been developed as economical alternatives but they are often slower or require higher temperatures. The trade-off is activity (speed of reaction) vs. cost of the catalyst and cost of the apparatus required for use of high pressures.

Two broad families of catalysts are known - homogeneous and heterogeneous. Homogeneous catalysts dissolve in the solvent that contains the unsaturated substrate. Heterogeneous catalysts are solids that are suspended in the same solvent with the substrate or are treated with gaseous substrate. In the pharmaceutical industry and for special chemical applications, soluble " "homogeneous"" catalyst are sometimes employed, such as the rhodium-based compound known as Wilkinson's catalyst, or the iridium-based Crabtree's catalyst.

The activity and selectivity of catalysts can be adjusted by changing the environment around the metal, i.e. the coordination sphere. Different faces of a crystalline heterogeneous catalyst display distinct activities, for example. Similarly, heterogeneous catalysts are affected by their supports, i.e. the material upon with the heterogeneous catalyst is bound. Homogeneous catalysts are affected by their ligands. In many cases, highly empirical modifications involve selective "poisons." Thus, a carefully chosen catalyst can be used to hydrogenate some functional groups without affecting others, such as the hydrogenation of alkenes without touching aromatic rings, or the selective hydrogenation of alkynes to alkenes using Lindlar's catalyst. For prochiral substrates, the selectivity of the catalyst can be adjusted such that one enantiomeric product is produced.

Mechanism of reaction

Because of its technological relevance, metal-catalyzed “activation” of H2, has been the subject of considerable study, focusing on the reaction mechanisms of by which metals mediate these reactions. First of all isotope labeling using deuterium can be used to determine the regiochemistry of the addition:

- RCH=CH2 + D2 → RCHDCH2D

Essentially, the metal binds to both components to give an intermediate alkene-metal(H)2 complex. The general sequence of reactions is:

- binding of the hydrogen to give a dihydride complex ("oxidative addition"):

- LnM + H2 → LnMH2

- binding of alkene:

- LnM(η2H2) + CH2=CHR → Ln-1MH2(CH2=CHR) + L

- transfer of one hydrogen atom from the metal to carbon (migratory insertion)

- Ln-1MH2(CH2=CHR) → Ln-1M(H)(CH2-CH2R)

- transfer of the second hydrogen atom from the metal to the alkyl group with simultaneous dissociation of the alkane ("reductive elimination")

- Ln-1M(H)(CH2-CH2R) → Ln-1M + CH3-CH2R

Preceding the oxidative addition of H2 is the formation of a dihydrogen complex.

Temperatures

The reaction is carried out at different temperatures and pressures depending upon the substrate. Hydrogenation is a strongly exothermic reaction. In the hydrogenation of vegetable oils and fatty acids, for example, the heat released is about 25 kcal per mole (105 kJ/mol), sufficient to raise the temperature of the oil by 1.6-1.7 °C per iodine number drop.

Scope

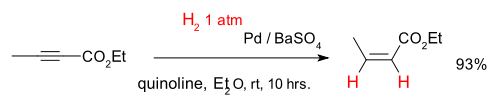

Alkynes can be selectively converted into alkenes in a so-called semihydrogenation, for instance with the compound Ethyl 2-Butynoate and catalyst palladium on barium sulfate and quinoline (which deactivates the catalyst enhancing chemoselectivity):

or with 4-(trimethylsilyl)-3-butyn-1-ol:

- 4-(trimethylsilyl)-3-butyn-1-ol hydrogenation

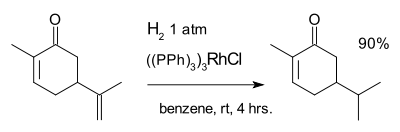

The next reaction featuring carvone is an example of homogeneous catalysis i.e. the Wilkinson's catalyst:

Hydrogenation is sensitive to steric hindrance explaining the selectivity for reaction with the exocyclic double bond but not the internal double bond.

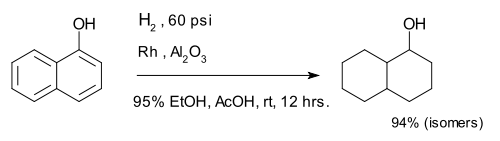

The compound 1-naphthol is completely reduced to a mixture of decalin-ol isomers.

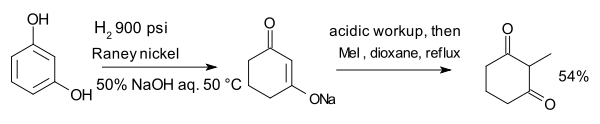

The compound resorcinol, hydrogenated with Raney nickel in presence of aqeous sodium hydroxide forms an enolate which is alkylated with methyl iodide to 2-methyl-1,3-cyclohexandione:

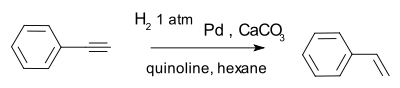

An effective catalyst is the Lindlar catalyst for example in the conversion of phenylacetylene to styrene.

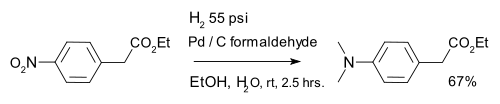

Hydrogenation is also used in organic reduction of nitro compounds, for instance aromatic nitro compounds in combination with palladium on carbon and formaldehyde:

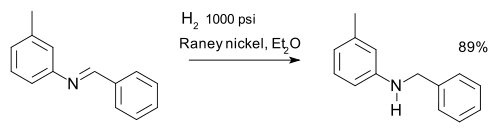

or the reduction of imines, for example in a synthesis of m-tolylbenzylamine:

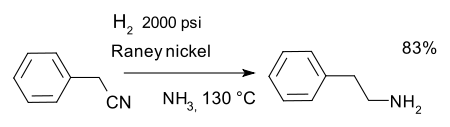

or the reduction of nitriles for instance in a synthesis of phenethylamine with Raney nickel and ammonia:

In the food industry

| Types of fats in food |

|---|

|

| See also |

|

Hydrogenation is widely applied to the processing of vegetable oils and fats. Complete hydrogenation converts unsaturated fatty acids to saturated ones. In practice the process is not usually carried to completion. Since the original oils usually contain more than one double bond per molecule (that is, they are poly-unsaturated), the result is usually described as partially hydrogenated vegetable oil; that is some, but usually not all, of the double bonds in each molecule have been reduced. This is done by restricting the amount of hydrogen (or reducing agent) allowed to react with the fat.

Hydrogenation results in the conversion of liquid vegetable oils to solid or semi-solid fats, such as those present in margarine. Changing the degree of saturation of the fat changes some important physical properties such as the melting point, which is why liquid oils become semi-solid. Semi-solid fats are preferred for baking because the way the fat mixes with flour produces a more desirable texture in the baked product. Since partially hydrogenated vegetable oils are cheaper than animal source fats, are available in a wide range of consistencies, and have other desirable characteristics (e.g., increased oxidative stability (longer shelf life)), they are the predominant fats used in most commercial baked goods. Fat blends formulated for this purpose are called shortenings.

Health implications

A side effect of incomplete hydrogenation having implications for human health is the isomerization of the remaining unsaturated carbon bonds. The cis configuration of these double bonds predominates in the unprocessed fats in most edible fat sources, but incomplete hydrogenation partially converts these molecules to trans isomers, which have been implicated in circulatory diseases including heart disease (see trans fats). The catalytic hydrogenation process favors the conversion from cis to trans bonds because the trans configuration has lower energy than the natural cis one. At equilibrium, the trans/cis isomer ratio is about 2:1. Food legislation in the US and codes of practice in EU has long required labels declaring the fat content of foods in retail trade, and more recently, have also required declaration of the trans fat content.

In 2006, New York City adopted the US's first major municipal ban on most artificial trans fats in restaurant cooking.

History

The earliest hydrogenation is that of platinum catalyzed addition of hydrogen to oxygen in the Döbereiner's lamp, a device commercialized as early as 1823. The French chemist Paul Sabatier is considered the father of the hydrogenation process. In 1897 he discovered that the introduction of a trace of nickel as a catalyst facilitated the addition of hydrogen to molecules of gaseous carbon compounds in what is now known as the Sabatier process. For this work Sabatier won half of the 1912 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Wilhelm Normann was awarded a patent in Germany in 1902 and in Britain in 1903 for the hydrogenation of liquid oils using hydrogen gas, which was the beginning of what is now a very large industry world wide. The commercially very important Haber-Bosch process (ammonia hydrogenation) was first described in 1905 and less so Fischer-Tropsch process (carbon monoxide hydrogenation) in 1922. Another commercial application is the oxo process (1938), a hydrogen mediated coupling of aldehydes with alkenes. Wilkinson's catalyst was the first homogeneous catalyst developed in the 1960s and Noyori asymmetric hydrogenation (1987) one of the first applications in asymmetric synthesis. A 2007 review article advocated the use of more hydrogenations in C-C coupling reactions like the oxo process.

Metal-free hydrogenation

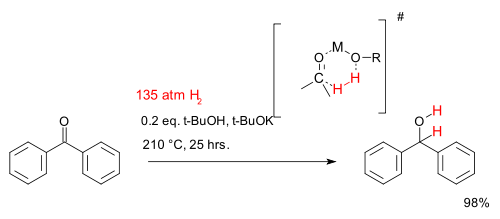

Although for all practical purposes hydrogenation requires a metal catalyst there exist some metal-free catalytic systems that are investigated in academic research. One such system for reduction of ketones consists of tert-butanol and potassium tert-butoxide and very high temperatures. The reaction depicted below describes the hydrogenation of benzophenone:

A chemical kinetics study found this reaction is first order in all three reactants suggesting a cyclic 6-membered transition state.

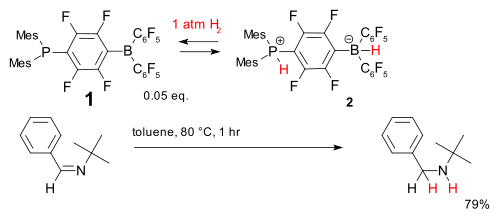

Another system is based on the phosphine- borane compound (1). It reversibly accepts dihydrogen at relatively low temperatures to form the phosphonium borate 2 which is able to reduce a simple hindered imine.