Battle of the Somme

Background to the schools Wikipedia

SOS believes education gives a better chance in life to children in the developing world too. With SOS Children you can choose to sponsor children in over a hundred countries

| Somme Offensive | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Western Front of the First World War | |||||||

Men of the 11th Battalion The Cheshire Regiment, near La Boisselle July 1916. Photo by Ernest Brooks. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 13 British and 11 French divisions totaling 280,000 men (initial) 51 British and 48 French divisions totalling 1,200,000 men (final) |

10½ divisions totaling 260,000 men (initial) 50 divisions totaling 1,375,000 men (final) |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 623,907 casualties 782 aircraft lost |

465,000 men, other credible estimates of c. 400,000 – c. 500,000, see article | ||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

The Battle of the Somme (French: Bataille de la Somme, German: Schlacht an der Somme), also known as the Somme Offensive, took place during the First World War between 1 July and 18 November 1916 on either side of the river Somme in France. The battle saw the British Expeditionary Force and the French Army mount a joint offensive against the German Army, which had occupied a large part of the north of France since its invasion of the country in August 1914. The Battle of the Somme was one of the largest battles of the war; by the time fighting paused in late autumn 1916, the forces involved had suffered more than 1 million casualties, making it one of the bloodiest military operations ever recorded.

The plan for the Somme offensive evolved out of Allied strategic discussions at Chantilly, Oise in December 1915. Chaired by General Joseph Joffre, the commander-in-chief of the French Army at the time, Allied representatives agreed on a concerted offensive against the Central Powers in 1916 by the French, British, Italian and Russian armies. The Somme offensive was to be the Anglo-French contribution to this general offensive and was intended to create a rupture in the German line which could then be exploited with a decisive blow. With the German attack on Verdun on the River Meuse in February 1916, the Allies were forced to adapt their plans. The British Army took the lead on the Somme, though the French contribution remained significant.

The opening day of the battle saw the British Army suffer the worst day in its history, sustaining nearly 60,000 casualties. Because of the composition of the British Army, at this point a volunteer force with many battalions comprising men from particular localities, these losses (and those of the campaign as a whole) had a profound social impact. The battle is also remembered for the first use of the tank. At the end of the battle in mid-November, British and French forces had penetrated 6 miles (9.7 km) into German occupied territory, with the British Army still three miles (5 km) from Bapaume, a major objective. The German Army maintained much its front line over the winter of 1916–1917, before withdrawing from the Somme battlefield in February 1917 to the fortified Hindenburg Line.

The conduct of the battle has been a source of controversy: senior officers such as General Sir Douglas Haig, the commander of the British Expeditionary Force and Henry Rawlinson, the commander of Fourth Army, have been criticised for the human cost while failing to achieve their territorial objectives. Historians such as W. Philpott, G. Sheffield and J. Sheldon have concluded that the Somme saw the beginning of modern all-arms warfare, when the BEF learned many tactical and operational lessons and that the battle inflicted serious damage on the German army, which was a preliminary to its eventual defeat in 1918.

Prelude

State of the armies

The original British Expeditionary Force of six divisions at the start of the war, had lost most of the army's pre-war regular soldiers in the battles of 1914 and 1915. The bulk of the army was made up of volunteers of the Territorial Force and Lord Kitchener's New Army, which had begun forming in August 1914. The expansion demanded generals for the senior commands, so promotion came at a rapid pace and did not always reflect ability. Haig started the war as the commanding officer of British I Corps, then was promoted to command the British First Army and then the BEF, an army group eventually comprising sixty divisions in five armies. This vast increase in numbers diluted troop quality, created an acute equipment shortage and correspondingly reduced the demands that new commanders were willing to make on their subordinates. Many officers tended to overcentralise, prescribe in great detail and leave as little to chance or initiative as possible, this was especially true of Sir Henry Rawlinson, the Fourth Army commander. Paradoxically, divisional commanders were given great latitude in training and detailed planning for the attack of 1 July, since the heterogeneous nature of the 1916 army made it impossible for Corps and Army level decisions to reflect the capacity of each division.

Allied strategy in 1916

Lead by Joseph Joffre, the Allied war strategy for 1916 was largely formulated during a conference at Chantilly between 6–8 December 1915. It was decided that for the next year, simultaneous offensives would be mounted by the Russian Empire in the east, Italy (which had entered the war on 23 May 1915) in the Alps and the Anglo-French on the Western Front, thereby assailing the Central Powers from all sides.

On 19 December 1915, General Sir Douglas Haig replaced General Sir John French as Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force. Haig favoured a British offensive in Flanders, close to BEF supply routes via the Channel ports and had a strategic goal of driving the Germans from the Belgian coast and eliminating the U-boat base at Bruges.

The British were still the "junior partner" on the Western Front and had to largely comply with French policy, even though Haig was not formally subordinate to General Joseph Joffre, the French Commander. In January 1916, Joffre had agreed to the BEF making their main effort in Flanders but after further discussions in February, it was decided to mount a combined offensive where the French and British armies met, astride the Somme River in Picardy before the British offensive in Flanders. In February 1916 the Germans began an offensive against the French at Verdun. The defence of Verdun reduced the French army's capacity to carry out their role on the Somme leaving the British commitment relatively larger, the balance of forces changing to 13 French and 20 British divisions. France would end up contributing three corps to the opening of the attack (the XX, I Colonial and XXXV Corps of the Sixth Army). Due to the cost of the battle at Verdun the aim of the Somme offensive changed from delivering a decisive blow against Germany, to relieving the pressure on the French army.

British plan of attack

British intentions evolved as the military situation changed after the Chantilly Conference. The size of the French rifle contribution drastically fell and the urgency of the commencement of operations on the Somme increased as the cost to the French of the defence of Verdun increased. Assumptions on which British planning were based correspondingly changed; from providing a lesser part of the offensive the British assumed the main role. Differences over tactics arose between Sir Douglas Haig and his senior local commander, General Sir Henry Rawlinson, General Officer Commanding the British Fourth Army. Haig had ordered that the objectives were "... relieving the pressure on the French at Verdun and inflicting loss on the enemy." ('G.H.Q. letter O.A.D. 12 to General Sir H. Rawlinson, 16 June 1916 Stating the Objectives') and that preparations should be made for an advance of 7 miles (11 km) to Bapaume should German resistance crumble, "If the first attack goes well every effort must be made to develop the success to the utmost by firstly opening a way for our cavalry and then as quickly as possible pushing the cavalry through to seize Bapaume...." (Note O.A.D. 17, Dated 21 June 1916). He prepared to do this by first bombarding the enemy relentlessly for a week with a million shells. Following up this massive display of artillery would be twenty-two British and French divisions, passing through the barriers and occupying the trenches filled with stunned German soldiers so that his divisions could head off into the open. He wrote to the British General Staff that "the advance was to be pressed eastward far enough to enable our cavalry to push through into the open country beyond the enemy's prepared lines of defence."

Rawlinson anticipated an advance in the form of "bites" into the German defences. This "bite and hold" method was based upon his experience, as in the Second Battle of Ypres where the Germans used 2,000 yards (1,800 m) worth of solid defence in the face of fire to achieve success. He perceived this to be a sort of siege warfare that would be limited but positive as in action in Messines in 1915. Rawlinson would soon compromise with Haig's plan, despite his views on the matter. He gradually changed his mind over the physical approach offered by Haig and even went so far as to tell his soldiers that "the infantry would only have to walk over to take possession."

German strategy in 1916

The Chief of the German General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn intended to split the British and French alliance in 1916 and end the war, before the Entente's material superiority became crushing. To obtain decisive victory, Falkenhayn needed to find a way to break through the western front and defeat the large number of reserves, which the Entente could move into the path of a breakthrough. Falkenhayn wanted to provoke the French into attacking equally strong German defences by threatening a sensitive point, close to the existing front line. Falkenhayn chose to attack towards Verdun over the Meuse Heights, to capture ground which overlooked Verdun and make it untenable. The French would have to conduct a counter-offensive from ground dominated by the German army and ringed with masses of heavy artillery, inevitably leading to huge losses and bringing the French army close to collapse. The British would have no choice but to begin a hasty relief-offensive, intended to divert German attention from Verdun but would also suffer huge losses. If these catastrophic defeats were not enough, Germany would attack both armies and end the western alliance for good.

German defensive preparations

Falkenhayn hoped that the French situation would become so desperate due to losses at Verdun, that the British would attack prematurely with poorly-trained, ill-equipped and badly-led troops, which would have been the case had the German offensive at Verdun taken the Meuse heights in February or March as planned. Falkenhayn intended to destroy the expected British relief offensive and begin a counter-offensive if necessary, which would bring decisive victory. The unexpected length of the Verdun offensive and the underestimation of the need to replace far more exhausted units at Verdun, depleted the German strategic reserve placed behind the Sixth Army, (north of the Somme near Arras) and reduced the German counter-offensive strategy north of the Somme to passive and unyielding defence.

Despite considerable debate among German staff officers, Falkenhayn retained the concept of rigid defence in 1916. On the Somme front Falkenhayn's construction plan of January 1915 was complete. Barbed wire obstacles had been enlarged from one belt 5–10 yards (4.6–9.1 m) wide to two, 30 yards (27 m) wide and about 15 yards (14 m) apart. Double and triple thickness wire was used and laid 3–5 feet (0.91–1.5 m) high. The front line had been increased from one line to three, 150–200 yards (140–180 m) apart, the first trench occupied by sentry groups, the second (Wohngraben) for the front-trench garrison and the third trench for local reserves. The trenches were traversed and had sentry-posts in concrete recesses built into the parapet. Dugouts had been deepened from 6–9 feet (1.8–2.7 m) to 20–30 feet (6.1–9.1 m) deep, 50 yards (46 m) apart and large enough for 25 men. An intermediate line of strongpoints (Stutzpunktlinie) about 1,000 yards (910 m) behind the front line had been built. Communication trenches ran back to the reserve line, now termed the second line which was as well-built and wired as the first line. The second line was built beyond the range of Allied field artillery, to force an attacker to stop and move field artillery forward before assaulting the line.

After the Herbstschlacht ("Autumn Battle") in 1915, a third line another 3,000 yards (2,700 m) back from the Stutzpunktlinie was begun in February and was nearly complete when the battle began. German artillery was organised in a series of sperrfeuerstreifen ("barrage sectors") and each officer was expected to know the batteries covering his section of the front line and the batteries ready to engage fleeting targets. A telephone system was built, with lines buried 6 feet (1.8 m) deep for 5 miles (8.0 km) behind the front line, which connected the front line to the artillery. The Somme defences had two inherent weaknesses which elaboration had not remedied. The front trenches were on a forward slope, lined by white chalk from the subsoil and easily seen by ground observers. The defences were crowded towards the front trench, with a regiment having two battalions near the front-trench system and the reserve battalion divided between the Stutzpunktlinie and the second line, all within 2,000 yards (1,800 m) and most troops within 1,000 yards (910 m) of the front line, accommodated in the new deep dugouts. The concentration of troops at the front line on a forward slope, guaranteed that it would face the bulk of an artillery bombardment, directed by ground observers on clearly marked lines.

Battle of Albert, 1–13 July

Before the infantry advanced, the artillery had been called into action. Barrages in the past had depended on surprise and poor German bunkers for success; however, these conditions did not exist in the area of the Somme. To add to the difficulties involved in penetrating the German defences, of 1,437 British guns, only 467 were heavies, and just 34 of those were of 9.2" (234 mm) or greater calibre. In the end, only 30 tons of explosive would fall per mile of British front. Of the 12,000 tons fired, two thirds of it was shrapnel and only 900 tons of it was capable of penetrating bunkers. To make matters worse, British gunners lacked the accuracy to bring fire in on close German trenches, keeping a safe separation of 300 yards (270 m), compared to the French gunners' 60 yards (55 m)—and British troops were often less than 300 yd (270 m) away, meaning German fortifications were untouched by the barrage. The infantry then crawled out into no man's land early so they could rush the front German trench as soon as the barrage lifted. Despite the heavy bombardment, many of the German defenders had survived, protected in deep dugouts, and they were able to inflict a terrible toll on the infantry.

First day on the Somme: 1 July

"Before the blackness of their burst had thinned or fallen the hand of time rested on the half-hour mark, and all along that old front line of the English there came a whistling and a crying. The men of the first wave climbed up the parapets, in tumult, darkness, and the presence of death, and having done with all pleasant things, advanced across No Man's Land to begin the Battle of the Somme."

Zero hour was officially set at 7:30 am for 1 July 1916. Ten minutes prior to zero hour, an officer detonated a 40,000-pound (18,000 kg) mine beneath Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt. Originally the mine was supposed to be set off at zero hour but as the VIII Corps commander, Lt-Gen Hunter-Weston (who had wanted to detonate four hours earlier, a proposal which was vetoed by the Inspector of Mines at BEF GHQ), remembered, both the 29th Division commander and the Brigade commander that were involved in the planning fought for ten minutes prior to zero hour. He said that they were concerned about large pieces harming the advancing British infantry. A Royal Engineer in the 252nd Tunneling Company confirmed this, saying after the war that after he complained about the earlier time to the VIII Corps staff, they told him that the reason for the time was that they "feared the results of their men going across." Soon after, the remaining mines were set off, with the exception of one mine at Kasino Point, which detonated at 7:27 a.m. When zero hour came, there was a brief and unsettling silence as artillery shifted their aim to a new line of targets and the time of the infantry to advance had come.

The attack was made by thirteen British divisions- eleven from the Fourth Army and two from the Third Army) north of the Somme River and eleven divisions of the French Sixth Army just to the south of the river. They were opposed by the German Second Army of General Fritz von Below. The axis of the advance was centred on the Roman road that ran from Albert in the west to Bapaume 12 miles (19 km) to the northeast.

North of the Albert-Bapaume road, the advance was almost a complete failure. Communications were completely inadequate, as commanders were largely ignorant of the progress of the battle. A mistaken report by General Beauvoir De Lisle of the 29th Division proved to be fatal. By misinterpreting a German flare as success by the 87th Brigade at Beaumont Hamel, it led to the reserves being ordered forward. The eight hundred and one men from the 1st Newfoundland Regiment marched onto the battlefield from the reserves and only 68 made it out unharmed with over 500 of 801 dead. This one day of fighting had snuffed out a major portion of an entire generation of Newfoundlanders. British attacks astride the Albert-Bapaume road also failed, despite the explosion of two mines at La Boisselle. Here another tragic advance was made by the Tyneside Irish Brigade of the 34th Division, which started nearly one mile from the German front line, in full view of German machine-guns. The Irish Brigade was wiped out before it reached the front trench line.

In the sector south of the Albert-Bapaume road, the British and French divisions found greater success. Here the German defences were relatively weak, and the French artillery, which was superior in numbers and experience to the British, was highly effective. From Mametz to Montauban and the Somme River, all the first-day objectives were reached. Though the French XX Corps was to only act in a supporting role in this sector, in the event they would help lead the way. South of the Somme, French forces fared very well, surpassing their objectives. The I Colonial Corps departed their trenches at 9:30 am as part of a feint meant to lure the Germans opposite into a false sense of security. The feint was successful as, like the French divisions to the north, they advanced 5 miles (8.0 km). They had stormed Fay, Dompierre and Becquincourt, extending the capture of German lines along a fourteen mile (21 km) front from Mametz to Fay. To the right of the Colonial Corps, the XXXV Corps also attacked at 9:30 am but, having only one division in the first line, had made less progress. The German trenches had been overwhelmed, and the enemy had been surprised by the attack. Over 3,000 German prisoners had been taken and the French had captured 80 German guns.

The first day on the Somme achieved success for the southern Allied forces but suffered tactical disaster on 2/3 of the British front. Assessments of the success of the assault have been limited.

- Middlebrook claims that 1 July was a British success, for the Germans immediately started closing down their attack at Verdun. The British assault had been on such a scale that success, in this limited sense, had been inevitable. The terrible losses made it a success hardly worth having.

- Edmonds refers to disastrous loss of the finest manhood of the United Kingdom and Ireland for only a small gain of ground to show. He also writes that a substantial success had been won upon half the total frontage of the Allied attack; for the French astride the Somme, and the British between Maricourt and Fricourt had driven the enemy from his front position. In this area at least he had lost heavily in killed, wounded and prisoners, much of his artillery had been destroyed, and considerable disorganisation had set in. It would have been in accordance with the tactical principles of "siege-warfare in the field" if Sir Douglas Haig had stopped his attacks after the limited success of 1 July and proceeded to try elsewhere. Unfortunately such a course was not possible.

Although the Allied armies had not achieved all that they had hoped and expected on 1 July 1916, Philpott asserts that they momentarily gained the upper hand. While the German defence had not been broken completely, it had all but collapsed on a large section of its front astride the Somme. By the early afternoon, a 'broad breach' existed north of the river.

'However clumsy the British offensive, it had wrested the initiative from the Germans and was inflicting punishing casualties on them. Allied strategy was working.'

The British had suffered 19,240 dead, 35,493 wounded, 2,152 missing and 585 prisoners for a total loss of 57,470. This meant that in one day of fighting, 20% of the entire British fighting force had been killed, in addition to the complete loss of the Newfoundland Regiment as a fighting unit. Haig and Rawlinson did not know the scale of the casualties and injuries from the battle and actually considered resuming the offensive as soon as possible. In fact, Haig, in his diary the next day, wrote that "...the total casualties are estimated at over 40,000 to date. This cannot be considered severe in view of the numbers engaged, and the length of front attacked."

Continuing the attack: 2–13 July

German reaction by the General Staff to the first day's events was one of surprise; they did not expect such a big attack by the British. General Erich von Falkenhayn, agitated by the additional losses in one sector of the Somme front, sacked the Chief of Staff of the Second Army and replaced him with Colonel Fritz von Lossberg, his operations officer. Lossberg did not readily accept this promotion, as he vehemently disagreed with the conduct of the offensive at Verdun. He wanted it stopped and Falkenhayn agreed to this condition. He ultimately took control of the Second Army but Falkenhayn did not keep his promise and attacks in the Verdun sector went on. Von Lossberg contributed greatly to the German defence in his part of the front, scrapping the old ideas of front line defence with a new ' defence in depth' idea. Lines of German defenders would be held in reserve, poised at the ready while the thin front line would ensure a much smaller amount of casualties.

The decisive issue of the war depends on the victory of the Second Army on the Somme. We must win this battle in spite of the enemy's temporary superiority in artillery and infantry. The important ground lost in certain places will be recaptured by our attack after the arrival of reinforcements. The vital thing is to hold on to our present positions at all costs and to improve them. I forbid the voluntary evacuation of trenches. The will to stand firm must be impressed on every man in the army. The enemy should have to carve his way over heaps of corpses..."

Assessments by Haig and Rawlinson on 2 July were lacking in the failure to secure objectives during the first day of the offensive. Despite this, planning for their next move was conducted between Haig, Rawlinson and Joffre. Haig felt that gains in the south should be exploited, Rawlinson wanted to stick to the original plan by pressing along the entire front and Joffre demanded that Haig aim to capture the heights of Thiepval Ridge but Haig would not agree to this and Joffre then referred him to General Foch to settle the matter. Foch remembers that Haig was "upset with his losses... and that therefore he was not much inclined to attack again at Thiepval-Serre, but proposed to exploit the success farther south. This infuriated Joffre, who simply went for Haig, and was quite brutal."

On the morning of 3 July, the northern part of the front bisected by the Albert-Bapaume road had been a problem for the British, as only a part of La Boisselle had been taken. The road to Contalmaison beyond La Boisselle was important to the British because the town of Contalmaison enjoyed a high position where the Germans protected their artillery, a focal point in the centre of the front line. The position south of the Albert-Bapaume road proved to be much more favourable to the advancing British, where they had achieved success. The line from Fricourt to Mametz Wood and on to Delville Wood near Longueval was overrun in due course, however the line beyond was more difficult to navigate because of dense forests.

As the British struggled to jump-start their offensive, the French continued their rapid advance south of the Somme. By 3 July, only three of the twelve original divisions of the British army slated for attack had been active since the first day. Since a period of stagnation had set in on the British part of the front, a simmering hostility rose up among the rank and file of the French army. Officers in the Sixth Army even went so far as to call the offensive that had taken place so far "for amateurs by amateurs." Despite the negative feelings, the I Colonial Corps pressed on and by the end of the day, Méréaucourt Wood, Herbécourt, Buscourt, Chapitre Wood, Flaucourt and Asseviller were all in French hands. The first town to be captured was Frise which held a 77-gun battery, found intact by French soldiers. In so doing, 8,000 Germans had been made prisoner, while the taking of the Flaucourt plateau would allow Foch to move heavy artillery up to support the XX Corps on the north bank.

The French continued their attack on 5 July as Hem was taken. On 8 July, Hardecourt-aux-Bois and Monacu Farm (a veritable fortress, surrounded by hidden machine-gun nests in the nearby marsh) both fell, followed by Biaches, Maisonnette and Fortress Biaches on 9 July and 10 July.

Result of the battle

Thus, in ten days of fighting, on nearly a 121⁄2 miles (20 kilometres) front, the French 6th Army had progressed as far as six miles (10 km) at points. It had occupied the entire Flaucourt plateau (which constituted the principal defence of Péronne) while taking 12,000 prisoners, 85 cannon, 26 minenwerfers, 100 machine guns, and other assorted materials, all with relatively minimal losses.

For the British, the first two weeks of the battle had degenerated into a series of disjointed, small-scale actions, ostensibly in preparation for making a major push. From 3 to 13 July, Rawlinson's Fourth Army carried out 46 "actions" resulting in 25,000 casualties, but no significant advance. This demonstrated a difference in strategy between Haig and his French counterparts and was a source of friction. Haig's purpose was to maintain continual pressure on the enemy, while Joffre and Foch preferred to conserve their strength in preparation for a single, heavy blow.

The fact that the French and British lacked an overall commander was hardly a benefit for the Entente. British generals wouldn't accept that their soldiers should stand under French command, and the French generals argued in the same way for their soldiers. (It was first at the last winter of the war, in 1918, after strong pressure from the United States on the United Kingdom, that the French fieldmarshal Ferdinand Foch became supreme commander of the entire western front.)

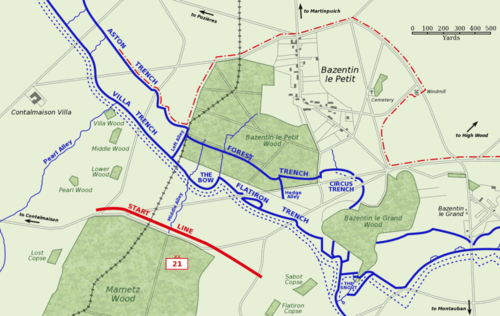

Battle of Bazentin Ridge, 14–22 July

On 14 July, the Fourth Army was finally ready to resume the offensive in the southern sector. The attack was aimed at capturing the German second defensive position which ran along the crest of the ridge from Pozières, on the Albert–Bapaume road, south-east towards the villages of Guillemont and Ginchy. The objectives were the villages of Bazentin le Petit, Bazentin le Grand and Longueval, which was adjacent to Delville Wood. Beyond this line, on the ridge, lay High Wood.

The preparation and execution of this attack contrasts sharply with that of 1 July. The attack on Bazentin Ridge was made by four divisions on a front of 6,000 yards (5.5 km) with the troops going over before dawn at 3:25 am after a surprise five-minute artillery bombardment. The artillery fired a creeping barrage and the attacking waves pushed up close behind it in no man's land, leaving them only a short distance to cross when the barrage lifted from the German front trench.

By mid-morning the first phase of the attack was a success with nearly all objectives taken, a gap also being made in the German defences. However, the British were unable to exploit it. Their attempt to do so created the most famous cavalry action of the Battle of the Somme, when the 7th Dragoon Guards and the 20th Deccan Horse attempted to capture High Wood. It is likely the infantry could have captured the wood in the morning but by the time the cavalry were in position to attack, the Germans had begun to recover. Though the cavalry held on in the wood through the night of 14 July, they had to withdraw the following day.

The British had a foothold in High Wood and would continue to fight over it as well as Delville Wood, neighbouring Longueval for many days. Unfortunately for them, the successful opening attack of 14 July did not mean they had learnt how to conduct trench battles. On the night of 22 July, Rawlinson launched an attack using six divisions along the length of the Fourth Army front that failed completely. The Germans were learning; they had begun to move away from trench-based defences and towards a flexible defence in depth system of strongpoints that was difficult for the supporting artillery to suppress.

Pozières and Mouquet Farm, 23 July–26 September

No significant progress was made in the northern sector in the first few weeks of July. Ovillers, just north of the Albert-Bapaume road, was not captured until 16 July; its capture and the foothold the British had obtained in the German second position on 14 July, meant that the chance existed for the German northern defences to be taken in the flank. The key to this was Pozières. The village of Pozières lay on the Albert-Bapaume road at the crest of the ridge. Just behind (east) the village ran the trenches of the German second position. The Fourth Army made three attempts to seize the village between 14 and 17 July before Haig relieved Rawlinson's army of responsibility for its northern flank. The capture of Pozières became a task for Gough's Reserve Army. He used the two Australian and one New Zealand divisions of I Anzac Corps.

Gough wanted the Australian 1st Division to attack immediately but the division's British commander, Major General Harold Walker, refused to send his men in without adequate preparation. The attack was scheduled for the night of 23 July to coincide with the Fourth Army attack of 22–23 July.

Going in shortly after midnight, the attack on Pozières was a success, largely thanks to Walker's insistence on careful preparation and an overwhelming supporting bombardment. An attempt to capture the neighbouring German second position failed, though two Australians were awarded the Victoria Cross in the attempt. The Germans, recognising the critical importance of the village to their defensive network, made three unsuccessful counter-attacks before beginning a prolonged and methodical bombardment of the village. The final German effort to reclaim Pozières came before dawn on 7 August following a particularly heavy bombardment. The Germans overran the forward Anzac defences and a mêlée developed from which the Anzacs emerged victorious.

Gough planned to drive north along the ridge towards Mouquet Farm, allowing him to threaten the German bastion of Thiepval from the rear. However, the further the Australians and New Zealanders advanced, the deeper was the salient they created such that the German artillery could concentrate on them from three directions.

On 8 August the Anzacs began pushing north along the ridge with the British II Corps advancing from Ovillers on their left. By 10 August a line had been established just south of the farm, which the Germans had turned into a fortress with deep dugouts and tunnels connecting to distant redoubts. The Anzacs made numerous attempts to capture the farm between 12 August and 3 September, inching closer with each attempt. The Anzacs were relieved by the Canadian Corps, who would briefly capture Mouquet Farm on 16 September, the day after the next major British offensive. The farm was finally overrun on 26 September and the garrison surrendered the following day.

By the time New Zealand's artillery was withdrawn from the line in October 1916, they had fired more than 500,000 shells at the Germans.

In the fighting at Pozières and Mouquet Farm, the Australian divisions suffered over 23,000 casualties, of which 6,741 were killed. If the losses from Fromelles on 19 July are included, Australia had sustained more casualties in six weeks in France than they had in the eight months of the Battle of Gallipoli. The New Zealanders suffered 8,000 casualties in six weeks – nearly one per cent of their nation's population. These losses were about the same as New Zealand suffered in eight months at Gallipoli.

Attrition: August and September

By the start of August, Haig had accepted that the prospect of achieving a breakthrough was now unlikely; the Germans had "recovered to a great extent from the disorganisation" of July. For the next six weeks, the British would engage in a series of small-scale actions in preparation for the next major push. On 29 August the German Chief of the General Staff, Erich von Falkenhayn, was replaced by General Paul von Hindenburg, with General Erich Ludendorff as his deputy, but in effect the operational commander. The immediate effect of this change was the introduction of a new defensive doctrine. On 23 September the Germans began constructing the Siegfried Stellung, called the Hindenburg Line by the British.

On the Fourth Army's front, the struggle for High Wood, Delville Wood and the Switch Line dragged on. The boundary between the British and French armies lay south-east of Delville Wood, beyond the villages of Guillemont and Ginchy. Here the British line had not progressed significantly since the first day of the battle, and the two armies were in echelon, making progress impossible until the villages were captured. The first British effort to seize Guillemont on 8 August was a debacle. On 18 August a larger effort began, involving three British corps as well as the French, but it took until 3 September before Guillemont was in British hands. Attention now turned to Ginchy, which was captured by the British 16th (Irish) Division on 9 September. The French had also made progress, and once Ginchy fell, the two armies were linked near Combles.

The British now had an almost straight front line from near Mouquet Farm in the north-west to Combles in the south-east, providing a suitable jumping-off position for another large-scale attack. In 1916 a straight front was considered necessary to enable the supporting artillery to lay down an effective creeping barrage behind which the infantry could advance.

This intermediate phase of the Battle of the Somme had been costly for the Fourth Army, despite there being no major offensive. Between 15 July and 14 September (the eve of the next battle), the Fourth Army made around 90 attacks of battalion strength or more with only four being general attacks across the length of the army's five miles (8 km) of front. The result was 82,000 casualties and an advance of approximately 1,000 yards (910 m)—a performance even worse than on 1 July.

Debut of the tank, 15–28 September

The last great Allied effort to achieve a breakthrough came on 15 September in the Battle of Flers-Courcelette with the initial advance made by 11 British divisions (nine from Fourth Army, two Canadian divisions on the Reserve Army sector) and a later attack by four French corps.

The battle is significantly remembered today as the debut of the tank. The British had high hopes that this secret weapon would break the deadlock of the trenches. Early tanks were not weapons of mobile warfare—with a top speed of 3 mph (4.8 km/h), they were easily outpaced by the infantry—but were designed for trench warfare. They were untroubled by barbed wire obstacles and impervious to rifle and machine-gun fire, though highly vulnerable to artillery. Additionally, the tanks were notoriously unreliable; of the 49 tanks available on 15 September, only 32 made it to the start line, and of these, only 21 made it into action. Mechanical breakdowns were common, and many others became bogged or ditched in the shell holes and trenches of the churned battlefield.

The British made gains across the length of their front, the greatest being in the centre at Flers with an advance of 3,500 yards (3.2 km), a feat achieved by the newest British division in France, the 41st Division, in their first action. They were supported by several tanks, including D-17 (known as Dinnaken) which smashed through the barbed wire protecting the village, crossed the main defensive trench and then drove up the main street, using its guns to destroy defenders in the houses. This gave rise to the optimistic press report: "A tank is walking up the High Street of Flers with the British Army cheering behind."

It was also the first major Western Front battle for the New Zealand Division, at the time part of XV Corps, which captured part of the Switch Line west of Flers. On the left flank, the Canadian 2nd Division particularly with the efforts of the French Canadian 22nd Battalion (the 'Van Doos') and the 25th Battalion (the Nova Scotia Rifles) captured the village of Courcelette after heavy fighting, with some assistance from two tanks. And finally after two months of fighting, the British captured all of High Wood, though not without another costly struggle. The plan was to use tanks in support of infantry from the 47th (1/2nd London) Division, but the wood was an impassable landscape of shattered stumps and shell holes, and only one tank managed to penetrate any distance. The German defenders were forced to abandon High Wood once British progress on the flanks threatened to encircle them.

The British had managed to advance during Flers-Courcelette, capturing 4,500 yards (4.1 km) of the German third position, but fell short of all their objectives, and once again the breakthrough eluded them. The tank had shown promise, but its lack of reliability limited its impact, and the military tactics of tank warfare were obviously in their infancy.

The least successful sector on 15 September had been east of Ginchy, where the Quadrilateral redoubt had held up the advance towards Morval—the Quadrilateral was not captured until 18 September. Another attack was planned for 25 September with the objectives of the villages of Thiepval; Gueudecourt, Lesbœufs and Morval. Like the Battle of Bazentin Ridge on 14 July, the limited objectives, concentrated artillery and weak German defences resulted in a successful attack and, although the number of tanks deployed was small, the tanks provided useful assistance in the destruction of machine-gun positions.

Final phase: 26 September – 18 November

On 26 September the Reserve Army exploited the success of the Fourth Army at the Battle of Morval 25–28 September, with the first big offensive north of the Albert–Bapaume road since 1 July, to attack Bazentin Ridge from north of Courcelette, west to the Schwaben Redoubt, on the ridge above Thiepval, overlooking the Ancre valley to the north. The Canadian Corps and II Corps divisions benefitted from time for training and planning, which combined with tanks, aircraft and overwhelming artillery support, led to an advance of approximately 1,000 yards (910 m) and the capture of Thiepval, with footings being gained in Stuff and Schwaben Redoubts by the 18th Division, the fall of Mouquet Farm and Zollern Redoubt to the 11th Division and the capture of part of the ridge by the 1st and 2nd Canadian Divisions, advancing from Courcelette from 28–30 September.

From 1 October – 11 November the Reserve Army attacked to complete the capture of Regina Trench/Stuff Trench, north of Courcelette and the west end of Bazentin Ridge around Schwaben and Stuff Redoubts, in the Battle of the Ancre Heights, during which bad weather caused great hardship and delay, against the Marine Brigade from Flanders and fresh German divisions brought from quiet fronts, which counter-attacked frequently; the British objectives were not secured until 11 November.

On 29 September Sir Douglas Haig made plans for the Third Army to take the area east of Gommecourt, the Reserve Army to attack north from Thiepval Ridge and east from Beaumont Hamel–Hébuterne and for the Fourth Army to reach the Péronne–Bapaume road around Le Transloy and Beaulencourt–Thilloy–Loupart Wood (north of the Albert–Bapaume road). The Battle of Le Transloy 1 October – 5 November began in good weather and Le Sars was captured on 7 October. Pauses were made from 8–11 October due to rain and 13–18 October to allow time for a methodical bombardment, when it became clear that the German defence had recovered from earlier defeats. Haig consulted with the army commanders and on 17 October reduced the scope of the next operations by cancelling the Third Army plans and reducing the Reserve Army and Fourth Army attacks to limited operations in co-operation with the French Sixth Army. Another pause followed before operations resumed on 23 October on the northern flank of the Fourth Army, with a delay during more bad weather on the right flank of the Fourth Army and on the French Sixth Army front, until 5 November. Next day the Fourth Army ceased offensive operations except for small attacks intended to improve positions and divert German attention from attacks being made by the Reserve/Fifth Army. Large operations resumed in January 1917.

The Battle of the Ancre 13–18 November was the last big British operation of the year. The Fifth (formerly Reserve) Army attacked into the Ancre valley from the south, along the Ancre River to the east and south-east on the north bank of the Ancre as far north as Serre. The intention was to exploit German exhaustion after the Battle of the Ancre Heights and gain ground ready for a resumption of the offensive in 1917. Political calculation, concern for Allied morale and Joffre's pressure for a continuation of attacks in France, to prevent German transfers to Russia and Italy also influenced Haig, although he stressed that the attack was not to be pursued at too great a risk.

The battle began on 13 November with another mine being detonated beneath Hawthorn Ridge Redoubt west of Beaumont Hamel. A brigade of the 31st Division attacked north of Serre forming the northern flank guard, before being withdrawn in the evening after the 3rd Division to the south was stopped in no man's land by the Serre garrison, which was not taken by surprise, having heard the British infantry advancing through the fog. South of Serre most of the objectives were taken; the 51st Division took Beaumont Hamel and the 63rd Division captured Beaucourt-sur-l'Ancre. South of the Ancre, II Corps captured St Pierre Divion and reached the outskirts of Grandcourt, while the Canadian 4th Division captured Regina Trench north of Courcelette. Desire Support Trench 400 yards (370 m) beyond Regina Trench was consolidated on 18 November. Large operations ended, until the renewal of pressure by the Fifth Army as soon as weather permitted, in January 1917. The British advanced 5 miles (8.0 km) on a 4 miles (6.4 km) front up the Ancre valley and caused the Germans to begin the withdrawal to the Hindenburg Line prematurely, in the area north of the Somme.

Conclusion

Foley argues that the Germans were caught by surprise by Allied firepower and the persistence of their attacks, which caused the Germans high casualties. The Germans adapted quickly and used better defensive methods, with the reinforcements which arrived in greater quantity during September. Opinion on the effect of the battle has varied, with much polemical writing and partisan point-scoring. An orthodox view that the British and French won a hard-fought victory against a skillful and brave enemy lasted until the early 1930s in English language writing, before being overturned by a revisionist view, found in the writings of Lloyd-George and Winston Churchill and the memoirists and fiction writers of the "disillusioned" school. In the 1960s this view became a new orthodoxy which (while challenged and academically undermined by research using primary sources) is still dominant in popular history and literature, while academic views have tended to revert to a nuanced version of the original school of thought, with information from German and French sources being used for comparison and heuristics like the "learning-curve" to explain the progress of the BEF from a hurriedly-raised, poorly-trained, poorly-led and poorly-equipped militia to a formidable mass army between 1915 and late 1916.

The British and French captured 7-mile (11 km) at the deepest point of penetration on a front of 16-mile (26 km) from Gommecourt to Maricourt thence from Maricourt to Foucaucourt-en-Santerre (and later south to Chilly). The French and British had gained approximately six miles in depth (to the foot of the Butte de Warlencourt and beyond Gueudecourt) and lost about 419,654 British and 202,567 French casualties against 465,181 German casualties, meaning that a centimetre cost about two men. Some historians have since the 1960s argued against the widely-held view that the battle was a disaster; arguing that the Battle of the Somme was an Allied victory. Gary Sheffield a British military historian wrote in 2003 that "The battle of the Somme was not a victory in itself, but without it the Entente would not have emerged victorious in 1918".

German experts are divided in their interpretation of the Somme. Some say it was a standoff, but most see it as a British victory and argue that it marked the point at which German morale began a permanent decline and the strategic initiative was lost, along with irreplaceable veterans and confidence.

Strategic effects

Prior to the battle, Germany had regarded Britain as a naval power and discounted her as a military force to be reckoned with, believing Germany's major enemies were France and Russia. According to some historians, starting with the Somme, Britain began to gain influence in the coalition. In recognition of the growing threat she posed, on 31 January 1917, Germany adopted the policy of unrestricted submarine warfare in an attempt to starve the island nation of supplies. Other historians would argue Britain's growing influence in the war had nothing to do with the battle and everything to do with her great financial and industrial strength, which inevitably increased in importance in a stalemate war.

At the start of 1916, the British Army had been a largely inexperienced and patchily trained mass of volunteers. The Somme was the first real test of this newly raised "citizen army" created by Lord Kitchener's call for recruits at the start of the war. Most British soldiers who were killed on the Somme, lacked experience and some historians have held that their loss was of lesser military significance than those of the German army. These soldiers had been the first to volunteer and so were often the fittest, most enthusiastic and best educated citizen soldiers. The British soldiers who survived the battle gained experience and the British Expeditionary Force learned how to conduct the mass warfare that the other armies had been fighting since 1914. For Germany, which had entered the war with a trained force of regulars and reservists, each casualty sapped the experience and effectiveness of the German army. The German Army Group Commander Crown Prince Rupprecht of Bavaria stated: "What remained of the old first-class peace-trained German infantry had been expended on the battlefield". Despite being promoted to Field-Marshal, Rupprecht infuriated the new German High Command (Hindenburg and Ludendorff) by advising them to make peace. A war of attrition was better for Britain with her population of some fifty million than Germany whose population of some seventy million also had to sustain operations against the French and Russians.

A school of thought, including John Terraine and recently William Philpott, holds that the Battle of the Somme placed unprecedented strain on the German Army and that after the battle it was unable to replace casualties like-for-like; which had the effect of closing any gap between the Allied and German army's effectiveness. Despite the strategic predicament of the German Army, it survived the battle and withstood the pressure of the Russian Brusilov Offensive and conducted an invasion of Romania. In 1917 the German army in the west survived British and French attacks at Arras, Champagne (the Nivelle Offensive) and the Third Battle of Ypres, although at great cost. The destruction of German units in battle was made worse by the lack of rest. British aircraft and long-range guns reached well behind the front-line where trench-digging and other work meant that troops returned to the line exhausted.

Falkenhayn was sacked and replaced by Hindenburg and Ludendorff in September 1916. At a conference at Cambrai on 5 September a decision was taken to build a new defensive line well behind the front line. The Siegfriedstellung was to be built between Arras–St Quentin–La Fere–Conde with another new line between Verdun and Pont-à-Mousson. These lines were intended to limit any Allied breakthrough and to allow the German army to withdraw if attacked. Work began on the Siegfriedstellung(Hindenburg Line) at the end of September. Withdrawing to the new line was not an easy decision and the German high command prevaricated over it during the winter of 1916–1917. Some members wanted to take a shorter step back to a line between Arras and Sailly, while the First and Second army commanders wanted to stay on the Somme. Generalleutnant von Fuchs in a meeting with General von Kuhl on 20 January 1917 said,

- Enemy superiority is so great that we are not in a position either to fix their forces in position or to prevent them from launching an offensive elsewhere. We just do not have the troops.... We cannot prevail in a second battle of the Somme with our men; they cannot achieve that any more. (Von Kuhl, Diary 20 January 1917)

half measures were futile; a retreat to the Siegfriedstellung was unavoidable. After the loss of a considerable amount of ground around the Ancre valley to the British Fifth Army in February 1917, the German army was given the order to begin the withdrawal from the Somme front Operation Alberich on 16 March 1917, despite the new line being unfinished and poorly sited in some places.

On 24 February 1917, the German army began Operation Alberich, the strategic scorched earth withdrawal from the Somme battlefield to the Siegfriedstellung ( Hindenburg Line), thereby shortening the front line they had to occupy. The purpose of military commanders is not to test their army to destruction and it has been suggested German commanders did not believe the army could endure continual battles of attrition like the Somme. German losses and the manpower crisis they caused, meant that 154 divisions were facing 190 Allied divisions, many being larger than German divisions. The Alberich Bewegung ("movement") shortened the Western Front and saved the German army the manpower of 13 divisions. Loss of German territory was repaid many times over in the strengthening of defensive lines, an option which was not open to the Allies because of the political impossibility of surrendering French or Belgian territory.

The strategic effects of the Battle of the Somme cannot obscure the fact it was one of the costliest battles of the First World War. A German officer, Friedrich Steinbrecher, wrote:

Somme. The whole history of the world cannot contain a more ghastly word.—Friedrich Steinbrecher

Another, Captain von Hentig, described the Battle of the Somme as "the muddy grave of the German Field Army".

Casualties

| Nationality | Total casualties |

Killed & missing |

Prisoners |

|---|---|---|---|

| United Kingdom | 350,000+ | - | - |

| Canada | 24,029 | - | - |

| Australia | 23,000 | < 200 | |

| New Zealand | 7,408 | - | - |

| South Africa | 3,000+ | - | - |

| Newfoundland | 2,000+ | - | - |

| Total British Commonwealth | 419,654 | 95,675 | - |

| French | 204,253 | 50,756 | - |

| Total Allied | 623,907 | 146,431 | - |

| Germany | 465,000 | 164,055 | 31,000 |

The original Allied estimate of casualties on the Somme, made at the Chantilly conference on 15 November, was 485,000 British and French casualties and 630,000 German. These figures were used to support the argument that the Somme was a successful battle of attrition for the Allies. However, there was considerable scepticism at the time of the accuracy of the counts.

After the war a final tally showed that 419,654 British in the Official History (Captain Wilfrid Miles the main author of that volume) and 204,253 French (in their own Official History) were killed, wounded, or taken prisoner; of the 623,907 total casualties, 146,431 were either killed or missing. Allied casualties have been “established with reasonable exactitude”, but the German figures are subject to far more debate.

Prior & Wilson (2005) refer to the German Reichsarchiv figures quoted by Winston Churchill, showing German casualties (dead, missing and wounded) of 237,009 inflicted by the British. The Somme meant the British suffered losses at around a 2:1 ratio. However, the Germans also admitted to suffering around 270,000 casualties inflicted by the French between February and June 1916 and 390,000 between July and the end of the year (see statistical tables in Appendix J of Churchill's "World Crisis"). Churchill states that the Germans suffered 278,000 casualties at Verdun (which began in February) and some losses must have been in quieter sectors but many of these German casualties must have been inflicted by the French at the Somme. Churchill also states that Franco-German losses at the Somme were "much less unequal" than the Anglo-German ratios. In 1939, G. C.Wynne wrote that the German casualties in the Battle of the Somme showed an "increasingly heavy proportion" compared to earlier battles and that the flower of the German army was being lost along with severe losses of artillery and that the ten-to-one advantage of the Allies in artillery ammunition had an "inevitable" effect. In another account Prior & Wilson put total German Somme losses at 400,000, which was only to the Allies’ advantage if their resources greatly exceeded those of Germans, which in the circumstances of 1916 was far from certain.

Churchill’s claim (originally made in his 1 August 1916 memo, “The Blood Test”) was not that attrition was wrong, merely that it was being badly conducted and could only work if the Germans lost more than the Allies (the Allies had approximately twice the manpower of the Central Powers). He also claimed that German losses were not enough to consume its manpower reserves – whereas in fact the influx of German manpower in 1916 may have been because Germany was still moving to full mobilisation. The German Reichsarchiv later admitted that "(our) grave loss of blood affected Germany very much more heavily than the Entente", although Prior has also pointed out that a pure comparison of casualties is very crude – manpower reserves, industrial & agricultural output and financial strength also affect a country’s ability to sustain war, whilst Ludendorff later admitted that failure of German morale more than manpower losses led him to seek an armistice in 1918.

Churchill’s estimates were subjected to a strong attack from the Napoleonic historian Sir Charles Oman, who during the war had been responsible for estimating German losses from casualty reports in German newspapers and who put German losses at 530,000. The British official historian Sir James Edmonds had unofficially advised Churchill but queried his figures, claiming that 30% needed to be added to the German figures as they did not include men who were lightly wounded and could return to duty quickly, bringing the total up to 680,000, i.e. exceeding the Allied losses. There is “no clear substantiation” for this claim and it has been discredited. Edmonds's figures were criticised by Liddell Hart and G. C. Wynne, who put them at 500,000, and also by MJ Williams (Journal of the Royal United Service Institution, 1964 and 1966). In 1939 Wynne accepted the German figure of 465,000.The Official History figure was later amended to 582,919, supposedly after a report from the German Casualty Inquiry Office, although Williams (1966) suggested that this may be an error and actually Churchill’s Reichsarchiv figure for the whole Western Front.

A separate statistical report by the British War Office concluded that German casualties – on the British sector only – could be as low as 180,000 during the battle. In compiling his biography of General Rawlinson, Major-General Sir Frederick Maurice was supplied by the Reichsarchiv with a figure of 164,055 for the German killed or missing.

A more recent analysis of the German medical history (the Sanitaets Report, a separate data series from the Reichsarchiv figures) puts German losses including lightly wounded at about 15% higher than Churchill's figures (an extra 98,000 on the Western Front as a whole for 1916 over Churchill’s 630,000). Despite this adjustment Allied losses clearly exceeded German, although loss ratios improved as the war went on (James McRandle and James Quirk, “The Blood Test Revisited” in Journal of Military History 70 (2006)).

Kennedy, a US staff officer, commented that the victor is more likely to produce accurate figures than the vanquished. German returns are incomplete and often contradictory. The German Official History states that between January and October 1916 the Germans suffered 1.4m “irreplaceable” (i.e. dead, prisoner and badly wounded but not lightly wounded) losses on all fronts, 800,000 of which were from July onward. Philpott suggests that excluding losses at Verdun (330,000, many of which were between February and July), on the Eastern Front where there were fewer German divisions and “wastage” in quiet sectors, Germany suffered over 500,000 irreplaceable losses at the Somme.

The average casualties per division (consisting of circa 18,000 soldiers) on the British sector up until 19 November was 8,026–6,329 for the four Canadian divisions, 7,408 for the New Zealand Division, 8,133 for the 43 British divisions and 8,960 for the three Australian divisions. The British daily loss rate during the Battle of the Somme was 2,943 men, which exceeded the loss rate during the Third Battle of Ypres but was not as severe as the two months of the Battle of Arras (1917) (4,076 per day) or the final Hundred Days offensive in 1918 (3,685 per day). The Royal Flying Corps "wrote off" 782 aircraft from all causes, 190 aircraft were recorded as "missing". 308 pilots and 191 observers were recorded as "killed, wounded or missing" during the battle and claimed 164 German aircraft destroyed and 205 damaged.

Also killed was an American-born soldier, Harry Butters, serving in the British Royal Artillery – the first American casualty in the First World War.

British mountaineers George Mallory and Bill Tilman survived the battle, along with the British writers J.R.R. Tolkien, Robert Graves, David Jones, and C.S. Lewis. Future British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan was wounded in the hip, leaving him with a lifelong shuffle to his walk. He was one of only two survivors from the 1912 class of 28 freshmen at Balliol College, Oxford.

Anecdotal evidence from the memoirs of Ernst Junger ("Storm of Steel") and future Chancellor Franz von Papen indicates severe German casualties during the attritional fighting of the summer and the Allied push of mid September, when British attacks had become more effective than earlier in the battle.

Adolf Hitler, then a Gefreiter of the 6th Bavarian Reserve Division, fought in the Battle of the Somme and was wounded, taking a bullet to the leg on 7 October 1916.

Notable deaths

- Augustin Cochin (French historian)

- Alan Seeger (American poet, volunteer in the French Foreign Legion)

- Reinhard Sorge (Expressionist writer; 1912 Kleist Prize recipient)

- Alban Arnold (British cricketer)

- Raymond Asquith (British barrister and son of the then Prime Minister)

- William Baker (British footballer)

- Guy Baring (British politician)

- Donald Simpson Bell (British footballer)

- Major Booth (British cricketer)

- William Buckingham (British recipient of the Victoria Cross)

- William Burns (British cricketer)

- George Butterworth (British composer)

- Geoffrey Cather (British recipient of the Victoria Cross)

- Cecil Christmas (British footballer)

- Christopher Collier (British cricketer)

- Billy Congreve (British recipient of the Victoria Cross)

- William Crozier (Irish cricketer)

- Bernard Donaghy (Irish footballer)

- Edward Dwyer (British recipient of the Victoria Cross)

- Charles Duncombe, 2nd Earl of Feversham (British politician)

- Alfred Flaxman (British athlete)

- Alan Foster (British footballer)

- Rowland Fraser (British rugby union player)

- Albert Gill (British recipient of the Victoria Cross)

- Duncan Glasfurd (British army officer)

- John Leslie Green (British recipient of the Victoria Cross)

- Fred Longstaff (British rugby league player)

- Billy McFadzean (Irish recipient of the Victoria Cross)

Commemoration

The Royal British Legion with the British Embassy in Paris and the Commonwealth War Graves Commission commemorate the battle on 1 July each year at the Thiepval Memorial to the Missing.

For their efforts on the first day of the battle, The 1st Newfoundland Regiment was given the name "The Royal Newfoundland Regiment" by George V on 28 November 1917. Because of the slaughter, the first day of the Battle of the Somme is still commemorated in Newfoundland, remembering the "Best of the Best" at 11 am on the Sunday nearest to 1 July.

The Somme has iconic status in Northern Ireland due to the participation of the 36th (Ulster) Division. Since 1916 the first of July has been marked in commemoration by veterans' groups and also by unionist/Protestant groups such as the Orange Order. Since the start of the Northern Irish Troubles the date has become associated primarily with the Orange Order and is regarded by some as simply a part of the ' marching season', with no particular connection to the Somme. However, the British Legion and others still commemorate the battle on July first.

Historiography

- Van Hartesveldt, Fred R. The Battles of the Somme, 1916: Historiography and Annotated Bibliography (Greenwood Press 1996) Online edition