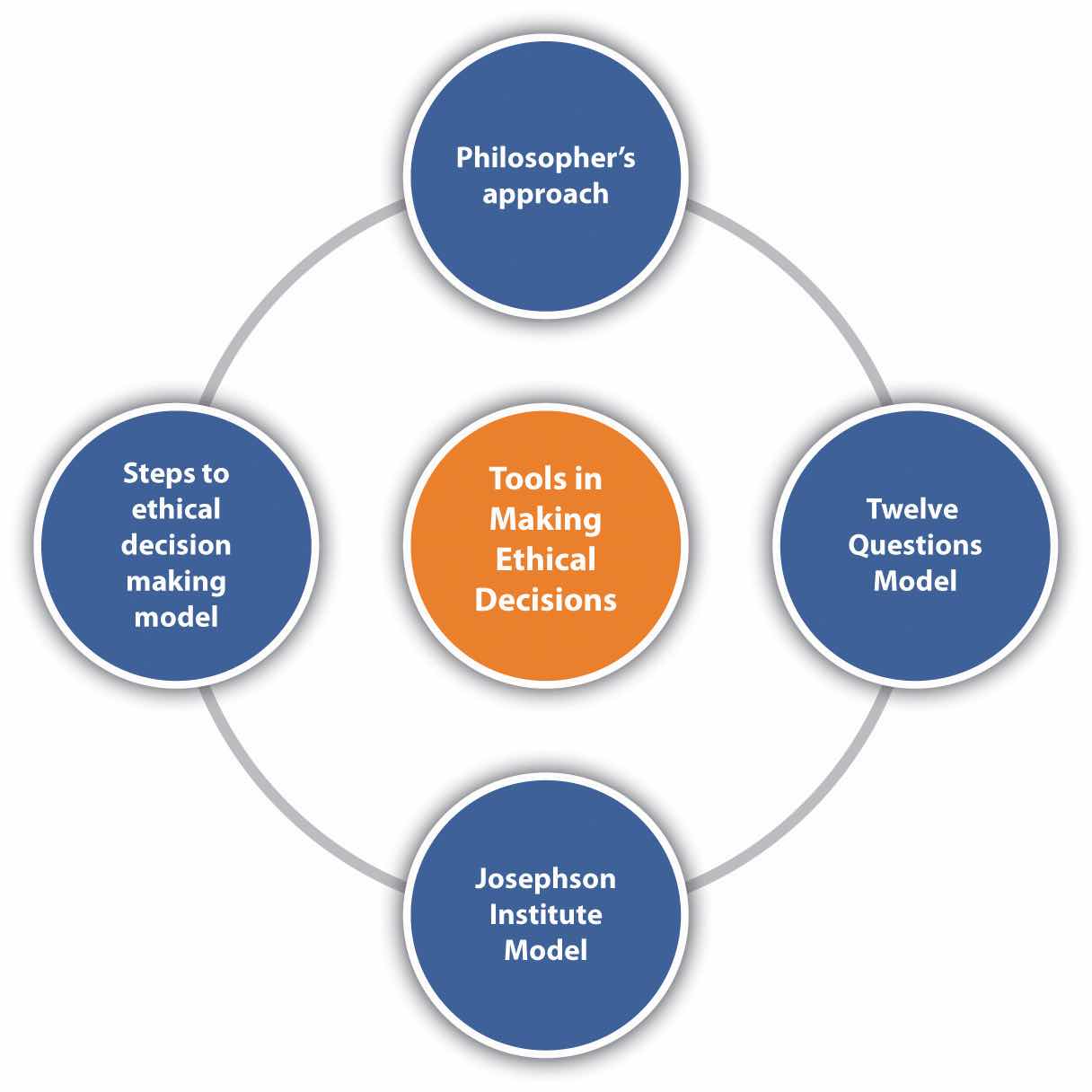

Now that we have working knowledge of ethics, it is important to discuss some of the models we can use to make ethical decisions. Understanding these models can assist us in developing our self-management skills and relationship management skills. These models will give you the tools to make good decisions, which will likely result in better human relations within your organization.

Note there are literally hundreds of models, but most are similar to the ones we will discuss. Most people use a combination of several models, which might be the best way to be thorough with ethical decision making. In addition, often we find ethical decisions to be quick. For example, if I am given too much change at the grocery store, I may have only a few seconds to correct the situation. In this case, our values and morals come into play to help us make this decision, since the decision making needs to happen fast.

Howard Gardner with University of Massachusetts Law School discusses ethics and youth.

Laura Nash, an ethics researcher, created the Twelve Questions Model as a simple approach to ethical decision making.Nash, L. (1981). Ethics without the sermon. Howard Business Review, 59 79–90, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.cs.bgsu.edu/maner/heuristics/1981Nash.htm In her model, she suggests asking yourself questions to determine if you are making the right ethical decision. This model asks people to reframe their perspective on ethical decision making, which can be helpful in looking at ethical choices from all angles. Her model consists of the following questions:Nash, L. (1981). Ethics without the sermon. Howard Business Review, 59 79–90, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.cs.bgsu.edu/maner/heuristics/1981Nash.htm

Consider the situation of Catha and her decision to take home a printer cartilage from work, despite the company policy against taking any office supplies home. She might go through the following process, using the Twelve Questions Model:

As you can see from the process, Catha came to her own conclusion by answering the questions involved in this model. The purpose of the model is to think through the situation from all sides to make sure the right decision is being made.

As you can see in this model, first an analysis of the problem itself is important. Determining your true intention when making this decision is an important factor in making ethical decisions. In other words, what do you hope to accomplish and who can it hurt or harm? The ability to talk with affected parties upfront is telling. If you were unwilling to talk with the affected parties, there is a chance (because you want it kept secret) that it could be the wrong ethical decision. Also, looking at your actions from other people’s perspectives is a core of this model.

Figure 5.3

Some of the possible approaches to ethical decision making. No one model is perfect, so understanding all of the possibilities and combining them is the best way to look at ethical decision making.

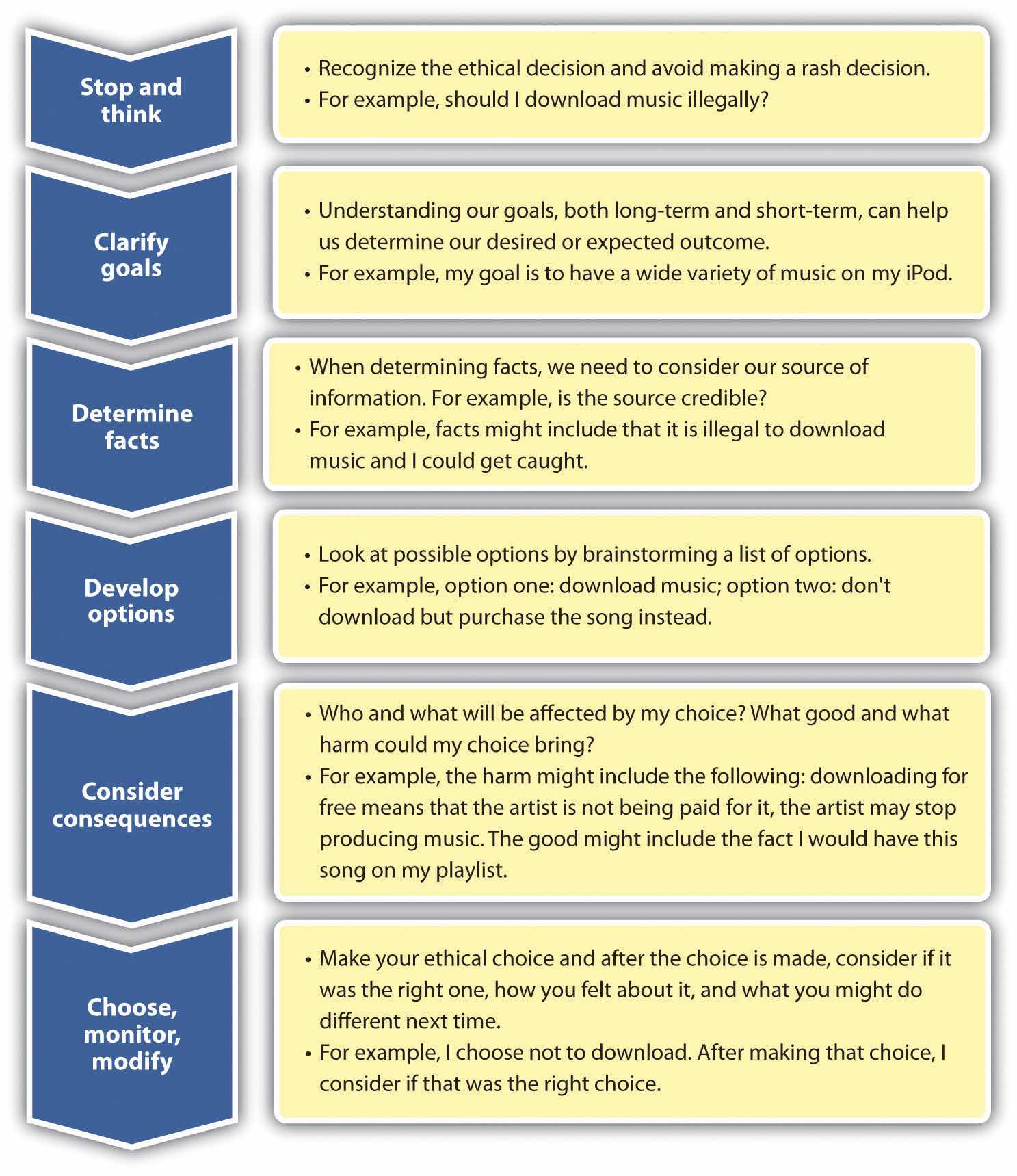

Josephson Institute of Ethics uses a model that focuses on six steps to ethical decision making. The steps consist of stop and think, clarify goals, determine facts, develop options, consider consequences, choose, and monitor/modify.

As mentioned, the first step is to stop and think. When we stop to think, this avoids rash decisions and allows us to focus on the right decision-making process. It also allows us to determine if the situation we are facing is legal or ethical. When we clarify our goals, we allow ourselves to focus on expected and desired outcomes. Next, we need to determine the facts in the situation. Where are we getting our facts? Is the person who is providing the facts to us credible? Is there bias in the facts or assumptions that may not be correct? Next, create a list of options. This can be a brainstormed list with all possible solutions. In the next step, we can look at the possible consequences of our actions. For example, who will be helped and who might be hurt? Since all ethical decisions we make may not always be perfect, considering how you feel and the outcome of your decisions will help you to make better ethical decisions in the future. Figure 5.4 "An Example of Josephson’s Model when Dealing with the Ethical Situation of Downloading Music from Share Websites." gives an example of the ethical decision-making process using Josephson’s model.

Figure 5.4 An Example of Josephson’s Model when Dealing with the Ethical Situation of Downloading Music from Share Websites.

There are many models that provide several steps to the decision-making process. One such model was created in the late 1990s for the counseling profession but can apply to nearly every profession from health care to business.Corey, G., Corey, M . S., & Callanan, P. (1998). Issues and ethics in the helping professions. Toronto: Brooks/Cole Publishing Company; Syracuse School of Education. (n.d.). An ethical decision making model, accessed February 24, 2012, http://soe.syr.edu/academic/counseling_and_human_services/modules/Common_Ethical_Issues/ethical_decision_making_model.aspx In this model, the authors propose eight steps to the decision-making process. As you will note, the process is similar to Josephson’s model, with a few variations:

Most organizations provide such a framework for decision making. By providing this type of framework, an employee can logically determine the best course of action. The Department of Defense uses a similar framework when making decisions, as shown in Note 5.14 "Department of Defense Decision-Making Framework".

The Department of Defense uses a specific framework to make ethical decisions.United States Department of Defense. (1999). Joint Ethics Regulation DoD 5500.7-R., accessed February 24, 2012, http://csweb.cs.bgsu.edu/maner/heuristics/1999USDepartmentOfDefense.htm and http://ogc.hqda.pentagon.mil/EandF/Documentation/ethics_material.aspx

Define the problem.

Identify the goals.

Name all the stakeholders.

Gather additional information.

State all feasible solutions.

Eliminate unethical options.

Philosophers and ethicists believe in a few ethical standards, which can guide ethical decision making. First, the utilitarian approachA source of ethical standards that says, when choosing one ethical action over another, we should select the one that does the most good and least harm. says that when choosing one ethical action over another, we should select the one that does the most good and least harm. For example, if the cashier at the grocery store gives me too much change, I may ask myself, if I keep the change, what harm is caused? If I keep it, is any good created? Perhaps the good created is that I am not able to pay back my friend whom I owe money to, but the harm would be that the cashier could lose his job. In other words, the utilitarian approach recognizes that some good and some harm can come out of every situation and looks at balancing the two.

In the rights approachA source of ethical standards that says we look at how our actions will affect the rights of those around us., we look at how our actions will affect the rights of those around us. So rather than looking at good versus harm as in the utilitarian approach, we are looking at individuals and their rights to make our decision. For example, if I am given too much change at the grocery store, I might consider the rights of the corporation, the rights of the cashier to be paid for something I purchased, and the right of me personally to keep the change because it was their mistake.

The common good approachA source of ethical standards that says, when making ethical decisions, we should try to benefit the community as a whole. says that when making ethical decisions, we should try to benefit the community as a whole. For example, if we accepted the extra change in our last example but donated to a local park cleanup, this might be considered OK because we are focused on the good of the community, as opposed to the rights of just one or two people.

The virtue approachA source of ethical standards that looks at desirable qualities and says we should act to obtain our highest potential. asks the question, “What kind of person will I be if I choose this action?” In other words, the virtue approach to ethics looks at desirable qualities and says we should act to obtain our highest potential. In our grocery store example, if given too much change, someone might think, “If I take this extra change, this might make me a dishonest person—which I don’t want to be.”

The imperfections in these approaches are threefold:Santa Clara University. (n.d.). A framework for thinking ethically, accessed February 24, 2012, http://www.scu.edu/ethics/practicing/decision/framework.html

Because of these imperfections, it is recommended to combine several approaches discussed in this section when making ethical decisions. If we consider all approaches and ways to make ethical decisions, it is more likely we will make better ethical decisions. By making better ethical decisions, we improve our ability to self-manage, which at work can improve our relationships with others.