In this section, we’re going to take a step further into the world of accounting by examining the principles of accrual accounting. In our Stress-Buster illustration, we’ve assumed that all your transactions have been made in cash: You paid cash for your inputs (plastic treasure chests and toys) and for your other expenses, and your customers paid cash when they bought Stress-Buster packs. In the real world, of course, things are rarely that simple. In the following cases, timing plays a role in making and receiving payments:

In situations such as these, firms use accrual accountingAccounting system that records transactions when they occur, regardless of when cash is paid or received.: a system in which the accountant records a transaction when it occurs, without waiting until cash is paid out or received. Here are a few basic principles of accrual accounting:

As we saw in our Stress-Buster illustration, it’s easier to make sense of accounting concepts when you see some real—or at least realistic—numbers being put to realistic use. So let’s now assume that you successfully operated the Stress-Buster Company while you were in college. Now fast-forward to graduation, and rather than work for someone else, you’ve decided to set up a more ambitious business—some kind of retail outlet—close to the college. During your four years in school, you noticed that there was no store near campus that met the wide range of students’ specific needs. Thus the mission of your proposed retail business: to provide products that satisfy the specific needs of college students.

Figure 12.13 The College Shop

You’ve decided to call your store “The College Shop.” Your product line will range from things needed to outfit a dorm room (linens, towels, small appliances, desks, rugs, dorm refrigerators) to things that are just plain fun and make student life more enjoyable (gift packages, posters, lava lamps, games, inflatable furniture, bean bag chairs, message boards, shower radios, backpacks). And of course you’ll also sell the original Stress-Buster Fun Pack. You’ll advertise to students and parents through the college newspaper and your own Web site.

At this point, we’re going to repeat pretty much the same process that we went through with your first business. First, we’ll prepare a beginning balance sheet that reflects your new company’s assets, liabilities, and owner’s equity on your first day of business—January 1, 20X6. Next, we’ll prepare an income statement and a statement of owner’s equity. Finally, we’ll create a balance sheet that reflects the company’s financial state at the end of your first year of business.

Although the process should now be familiar, the details of our new statements will be more complex—after all, your transactions will be more complicated: You’re going to sell and buy stuff on credit, maintain an inventory of goods to be sold, retain assets for use over an extended period of time, borrow money and pay interest on it, and deal with a variety of expenses that you didn’t have before (rent, insurance, etc.).

Your new beginning balance sheet contains the same items as the one that you created for Stress-Buster—cash, loans, and owner’s equity. But because you’ve already performed a broader range of transactions before you opened for business, you’ll need some new categories:

Obviously, then, you need to prepare a more sophisticated balance sheet than the one you created for your first business. We call this new kind of balance sheet a classified balance sheetBalance sheet that totals assets and liabilities in separate categories. because it classifies assets and liabilities into separate categories.

On a classified balance sheet, assets are listed in order of liquiditySpeed with which an asset can be converted into cash.—how quickly they can be converted into cash. They’re also broken down into two categories:

Your current assets will be cash and inventory, and your long-term assets will be furniture and equipment. We’ll take a closer look at the assets section of your beginning balance sheet, but it makes sense to analyze your liabilities first.

Liabilities are grouped in much the same manner as assets:

Recall that your liabilities come from your two loans: one which is payable in a year and considered current, and one which is long term and due in five years.

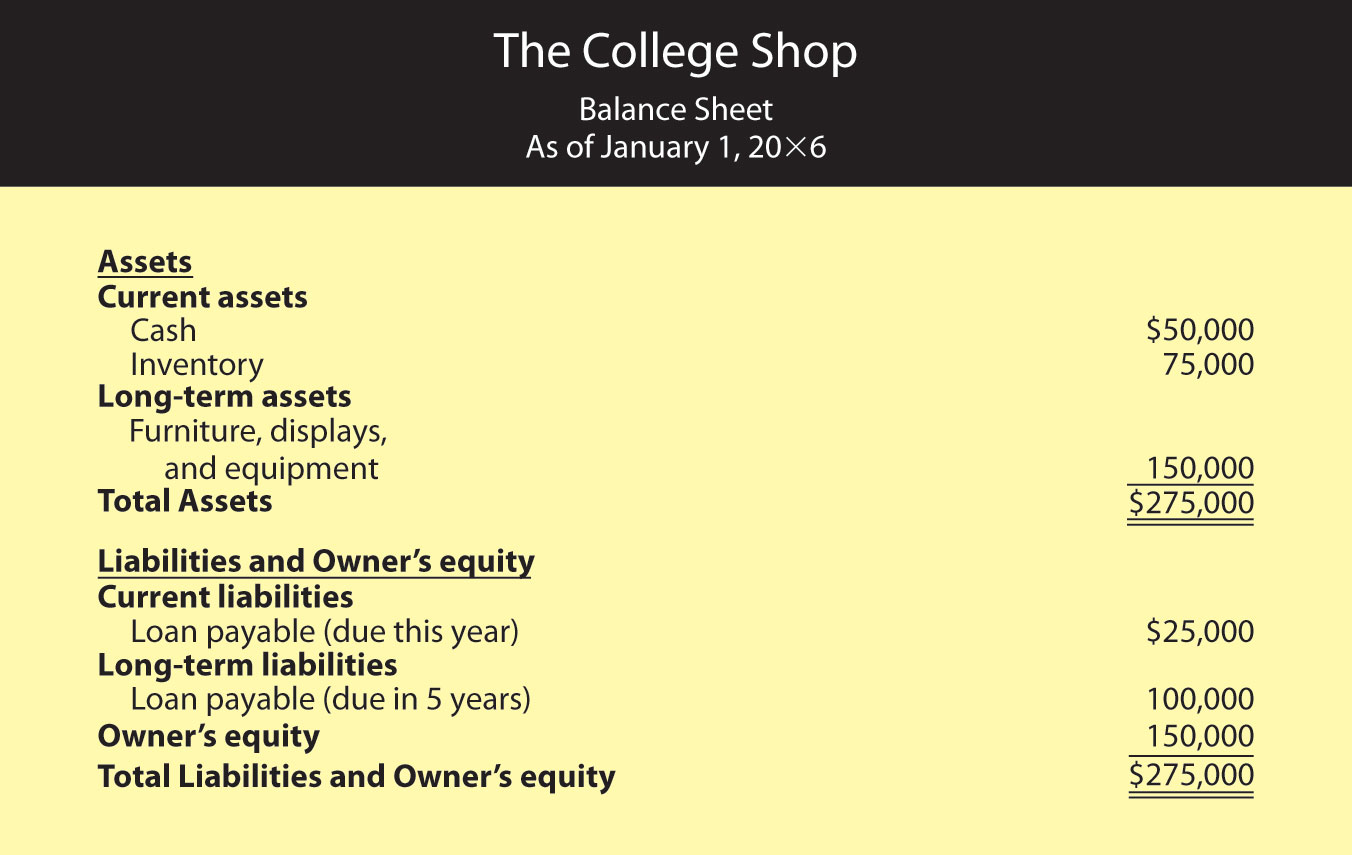

Now we’re ready to review your beginning balance sheet, which is shown in Figure 12.14 "Beginning Balance Sheet for The College Shop". Once again, your balance sheet balances: Your total assets of $275,000 equal your total liabilities plus owner’s equity of $275,000.

Figure 12.14 Beginning Balance Sheet for The College Shop

Let’s begin our analysis of your beginning balance sheet with the liabilities and owner’s-equity sections. We’re assuming that, thanks to a strong business plan, you’ve convinced a local bank to loan you a total of $125,000—a short-term loan of $25,000 and a long-term loan of $100,000. Naturally, the bank charges you interest (which is the cost of borrowing money); your rate is 8 percent per year. In addition, you personally contributed $150,000 to the business (thanks to a trust fund that paid off when you turned 21).

Now let’s turn to the assets section of your beginning balance sheet. What do you have to show for your $275,000 in liabilities and owner’s equity? Of this amount, $50,000 is in cash—that is, money deposited in the company’s checking and other bank accounts. You used another $75,000 to pay for inventory that you’ll sell throughout the year. Finally, you spent $150,000 on several long-term assets, including a sign for the store, furniture, store displays, and computer equipment. You expect to use these assets for five years, at which point you’ll probably replace them.

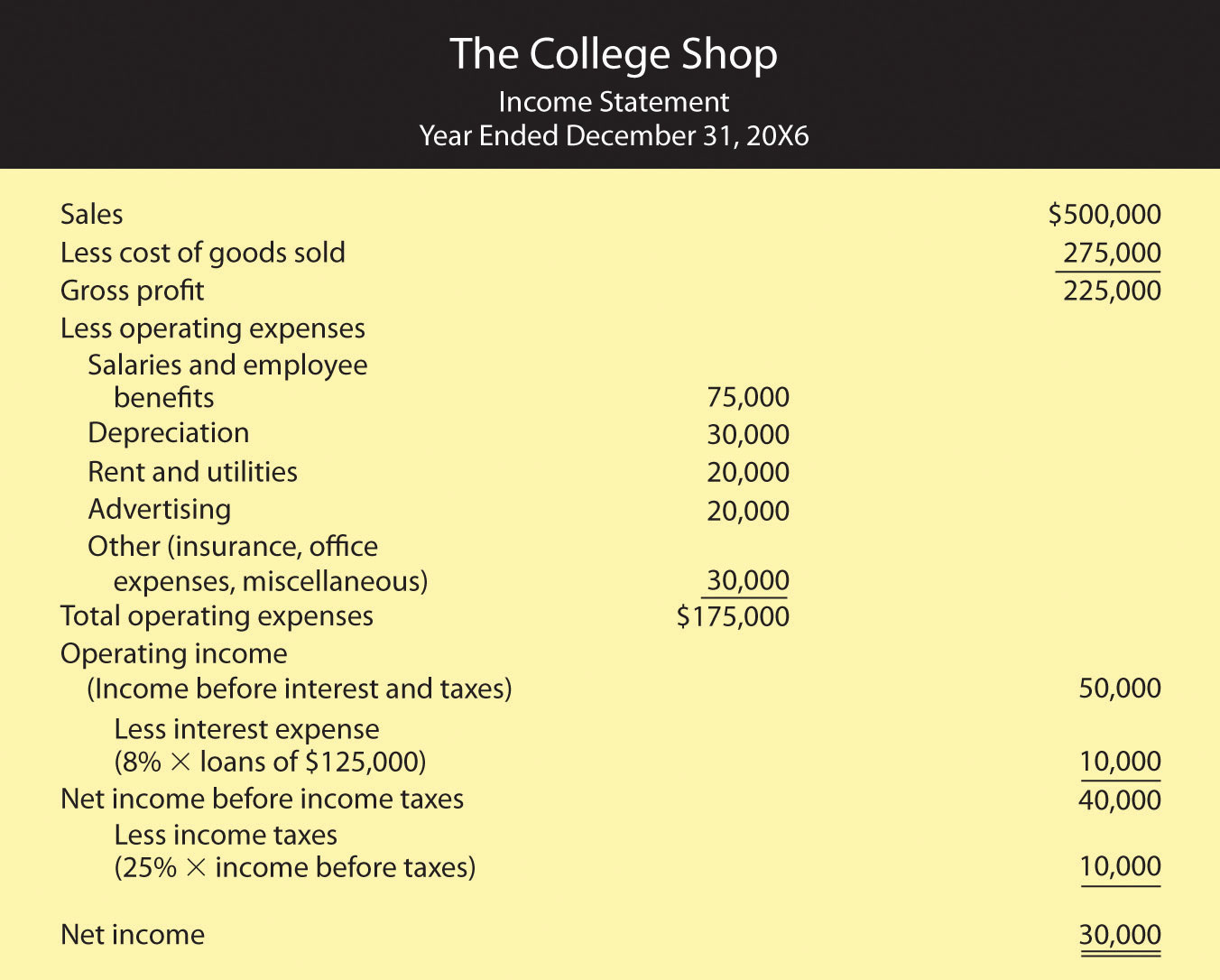

Finally, let’s look at your income statement, which is shown in Figure 12.15 "Income Statement for The College Shop, Year Ended December 31". Like your College Shop balance sheet, your College Shop income statement is more complex than the one you prepared for Stress-Buster, and the amounts are much larger. In addition, the statement covers a full calendar year.

Figure 12.15 Income Statement for The College Shop, Year Ended December 31

Note, by the way, that the income statement that we prepared for The College Shop is designed for a merchandiser—a company that makes a profit by selling goods. How can you tell? Businesses that sell services (such as accounting firms or airlines) rather than merchandise don’t have lines labeled cost of goods sold on their statements.

The format of this income statement also highlights the most important financial fact in running a merchandising company: you must sell goods at a profit (called gross profit) that is high enough to cover your operating costs, interest, and taxes. Your income statement, for example, shows that The College Shop generated $225,000 in gross profit through sales of goods. This amount is sufficient to cover your operating expense, interest, and taxes and still produce a net income of $30,000.

Note that The College Shop income statement also lists a few expenses that the Stress-Buster didn’t incur:

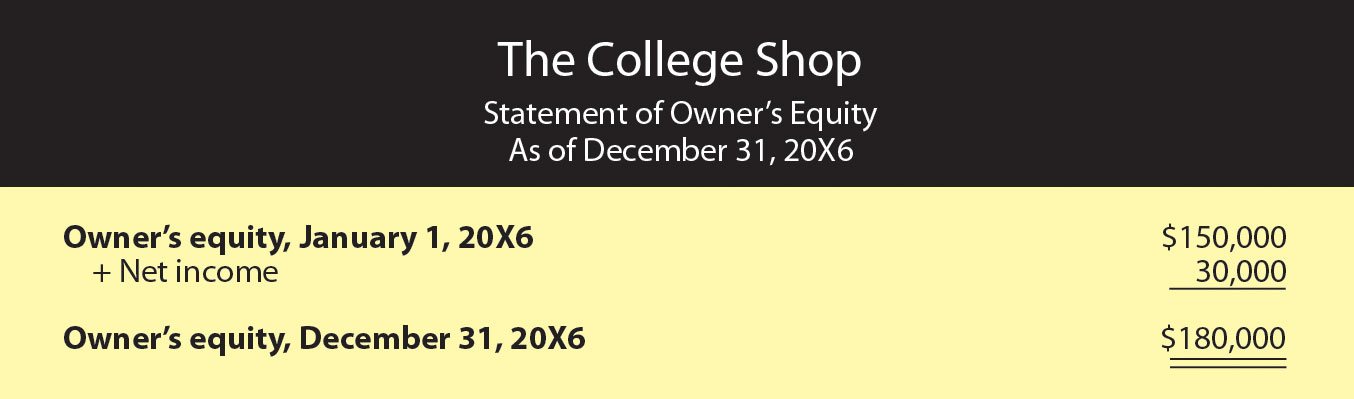

Our next step is to prepare a statement of owner’s equity, which is shown in Figure 12.16 "Statement of Owner’s Equity for The College Shop". Note that the net income of $30,000 from the income statement was used to arrive at the year-end balance in owner’s equity.

Figure 12.16 Statement of Owner’s Equity for The College Shop

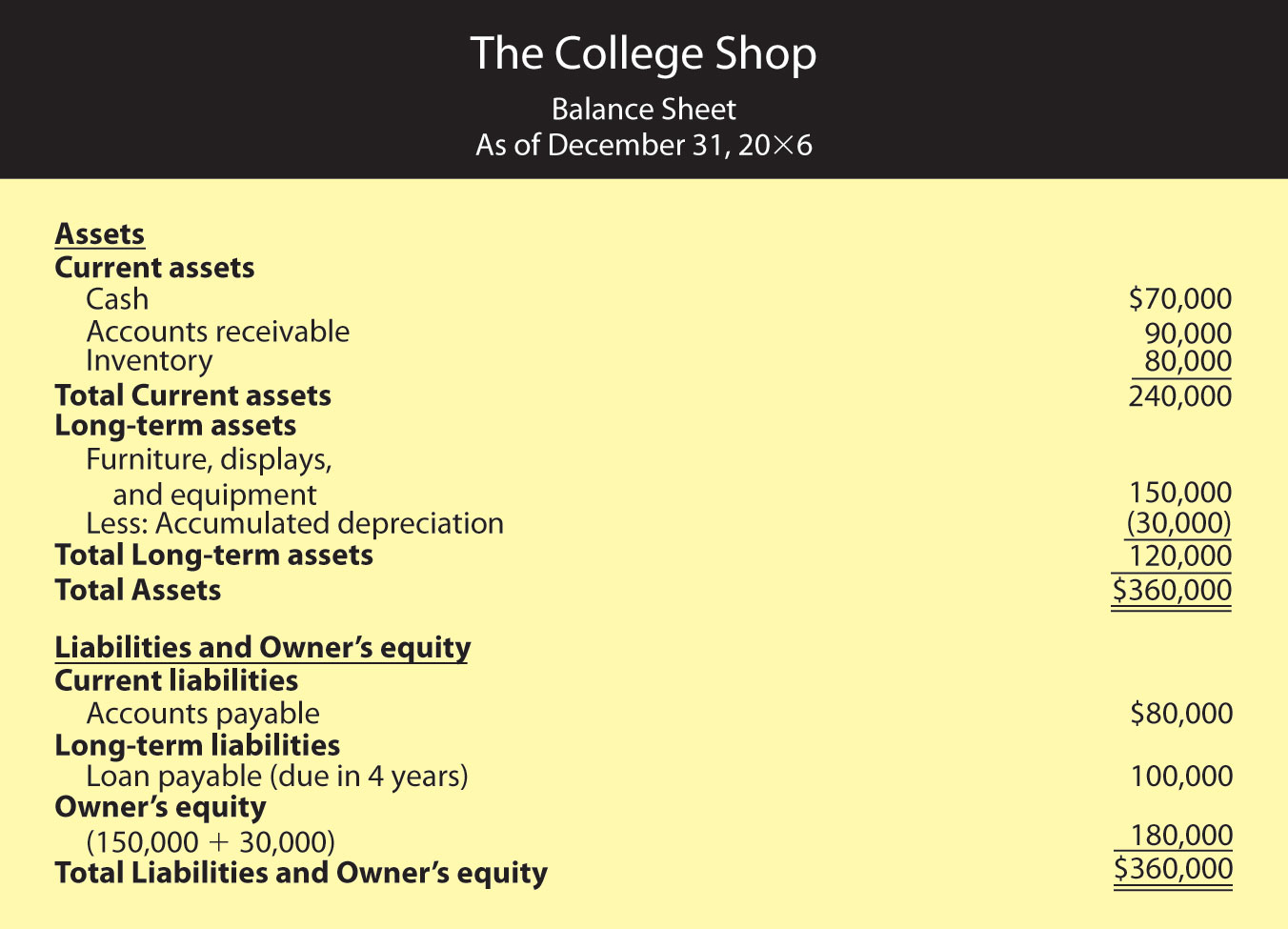

We’ll conclude with your balance sheet for the end of your first year of operations, which is shown in Figure 12.17 "End-of-Year Balance Sheet for The College Shop". First, look at your assets. At year’s end, you have a cash balance of $70,000 and inventory of $80,000. You also have an accounts receivable of $90,000 because many of your customers have bought goods on credit and will pay later. In addition, the balance sheet now shows two numbers for long-term assets: the original cost of these assets, $150,000, and an accumulated depreciation amount of $30,000, which reflects the amount that you’ve charged as depreciation expense since the purchase of the assets. The carrying value of these long-term assets is now $120,000 ($150,000 - $30,000), which is the difference between their original cost and the amount that they’ve been depreciated. Your total assets are thus $360,000.

Figure 12.17 End-of-Year Balance Sheet for The College Shop

The total of your liabilities of $180,000 plus owner’s equity of $180,000 also equals $360,000. Your liabilities consist of a long-term loan of $100,000 (which is now due in four years) and accounts payable of $80,000 (money that you’ll have to pay out later for purchases that you’ve made on credit). Your owner’s equity (your investment in the business) totals $180,000 (the $150,000 you originally put in plus the $30,000 in first-year earnings that you retained in the business).

Owners, investors, and creditors can learn a lot from your balance sheet and your income statement. Indeed, each tells its own story. The balance sheet tells what assets your company has now and where they came from. The income statement reports earned income on an accrual basis (recognizing revenues when earned and expenses as incurred regardless of when cash is received or paid). But the key to surviving in business is generating the cash you need to keep it up and running. It’s not unusual to hear reports about companies with cash problems. Sometimes they arise because the products in which the firm has invested aren’t selling as well as it had forecast. Maybe the company tied up too much money in a plant that’s too big for its operations. Maybe it sold products to customers who can’t pay. Maybe management just overspent. Whatever the reason, cash problems will hamper any business. Owners and other interested parties need a financial statement that helps them understand a company’s cash flow.

The statement of cash flowsFinancial statement reporting on cash inflows and outflows resulting from operating, investing, and financing activities. tells you where your cash came from and where it went. It furnishes information about three categories of activities that cause cash either to come in (cash inflows) or to go out (cash outflows):

A cash flow statement for The College Shop would look like the one in Figure 12.18 "Statement of Cash Flows for The College Shop". You generated $45,000 in cash from your company’s operations (a cash inflow) and used $25,000 of this amount to pay off your short-term loan (a cash outflow). The net result was an increase in cash of $20,000. This $20,000 increase in cash agrees with the change in your cash during the year as it’s reported in your balance sheets: You had an end-of-the-year cash balance of $70,000 and a beginning-of-the-year balance of $50,000 ($70,000 − $50,000 = $20,000). Because you didn’t buy or sell any long-term assets during the year, your cash flow statement shows no cash flows from investing activities.

Figure 12.18 Statement of Cash Flows for The College Shop

There are two different methods for reporting financial transactions:

A classified balance sheet separates assets and liabilities into two categories—current and long-term:

(AACSB) Analysis

To earn money to pay some college expenses, you ran a lawn-mowing business during the summer. Before heading to college at the end of August, you wanted to find out how much money you earned for the summer. Fortunately, you kept good accounting records. During the summer, you charged customers a total of $5,000 for cutting lawns (which includes $500 still owed to you by one of your biggest customers). You paid out $1,000 for gasoline, lawn mower repairs, and other expenses, including $100 for a lawn mower tune-up that you haven’t paid for yet. You decided to prepare an income statement to see how you did. Because you couldn’t decide whether you should prepare a cash-basis statement or an accrual statement, you prepared both. What was your income under each approach? Which method (cash-basis or accrual) more accurately reflects the income that you earned during the summer? Why?

(AACSB) Analysis

Identify the categories used on a classified balance sheet to report assets and liabilities. How do you determine what goes into each category? Why would a banker considering a loan to your company want to know whether an asset or liability is current or long-term?

(AACSB) Analysis

You review a company’s statement of cash flows and find that cash inflows from operations are $150,000, net outflows from investing are $80,000, and net inflows from financing are $60,000. Did the company’s cash balance increase or decrease for the year? By what amount? What types of activities would you find under the category investing activities? Under financing activities? If you had access to the company’s income statement and balance sheet, why would you be interested in reviewing its statement of cash flows? What additional information can you gather from the statement of cash flows?