After you have read this section, you should be able to answer the following questions:

Many of the arguments that we have just made about labor have analogies when we think about capital. Just as the amount of labor in an economy depends on the size of the workforce, so the amount of capital depends on the capital stock. Just as the amount of labor depends on how many hours each individual works, so the amount of capital depends on the utilization rate of capital.

Capital utilizationThe rate at which the existing capital stock is used. is the rate at which the existing capital stock is used. For example, if a manufacturing firm runs its production lines 24 hours per day, 7 days per week, then its capital utilization rate is very high.

Just as labor can migrate from country to country, so also capital may cross national borders. In the short run, the total amount of capital in an economy is more or less fixed. We cannot make a significant change to the capital stock in short periods of time. In the longer run, however, the capital stock changes because some of the real gross domestic product (real GDP) produced each year takes the form of new capital goods—new factories, machines, computers, and so on. Economists call these new capital goods investmentThe purchase of new goods that increase capital stock, allowing an economy to produce more output in the future..

Toolkit: Section 31.27 "The Circular Flow of Income"

Investment is one of the components of overall GDP.

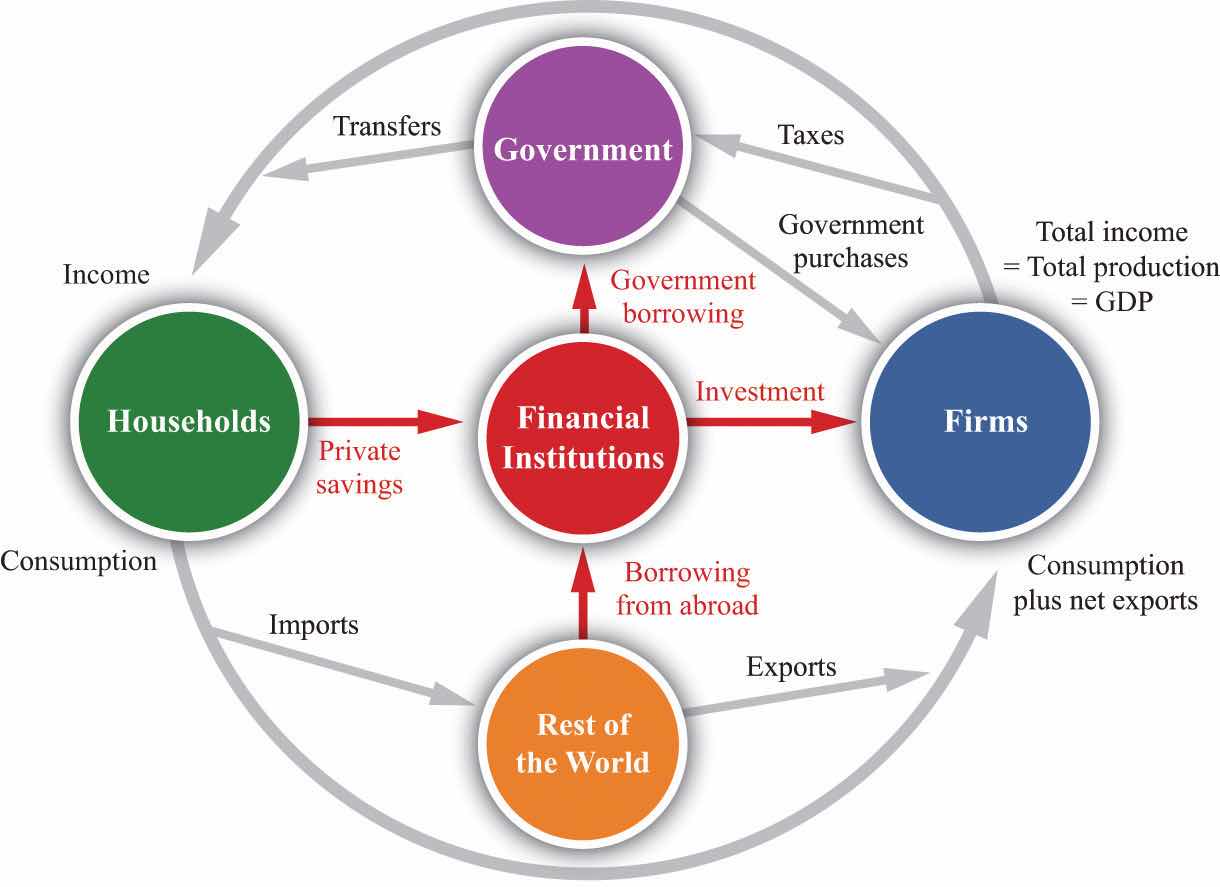

We can use the circular flow to help us understand how much investment there is in an economy. Figure 20.8 "The Flows In and Out of the Financial Sector" reviews the four flows of dollars in and out of the financial sector.The circular flow is introduced in Chapter 18 "The State of the Economy". We elaborate on it in Chapter 19 "The Interconnected Economy", Chapter 22 "The Great Depression", Chapter 27 "Income Taxes", and Chapter 29 "Balancing the Budget".

There is a flow of dollars between the financial sector and the government sector. This flow can go in either direction. Figure 20.8 "The Flows In and Out of the Financial Sector" is drawn for the case where the government is borrowing (there is a government deficitThe difference between government outlays and revenues.), so the financial markets send money to the government sector. In the case of a government surplus, the flow goes in the other direction. The national savingsThe sum of private and government saving. of an economy are the savings carried out by the private and government sectors taken together:

national savings = private savings + government surplus or national savings = private savings − government deficit.Figure 20.8 The Flows In and Out of the Financial Sector

The flows in and out of the financial sector must balance, which tells us that investment is financed by national savings plus borrowing from abroad.

The total flows in and out of the financial sector must balance. Because of this, as we see from Figure 20.8 "The Flows In and Out of the Financial Sector", there are two sources of funding for new physical capital: savings generated in the domestic economy and borrowing from abroad.

investment = national savings + borrowing from other countries.Or, in the case where we are lending to other countries,

investment = national savings − lending to other countries.Capital goods don’t last forever. Machines break down and wear out. Technologies become obsolete: a personal computer (PC) built in 1988 might still work today, but it won’t be much use to you unless you are willing to use badly outdated software and have access to old-fashioned 5.25-inch floppy disks. Buildings fall down—or at least require maintenance and repair.

DepreciationThe amount of capital stock that an economy loses each year due to wear and tear. is the term economists give to the amount of the capital stock that an economy loses each year due to wear and tear. Different types of capital goods depreciate at different rates. Buildings might stay standing for 50 or 100 years; machine tools on a production line might last for 20 years; an 18-wheel truck might last for 10 years; a PC might be usable for 5 years. In macroeconomics, we do not worry too much about these differences and often just suppose that all capital goods are the same.

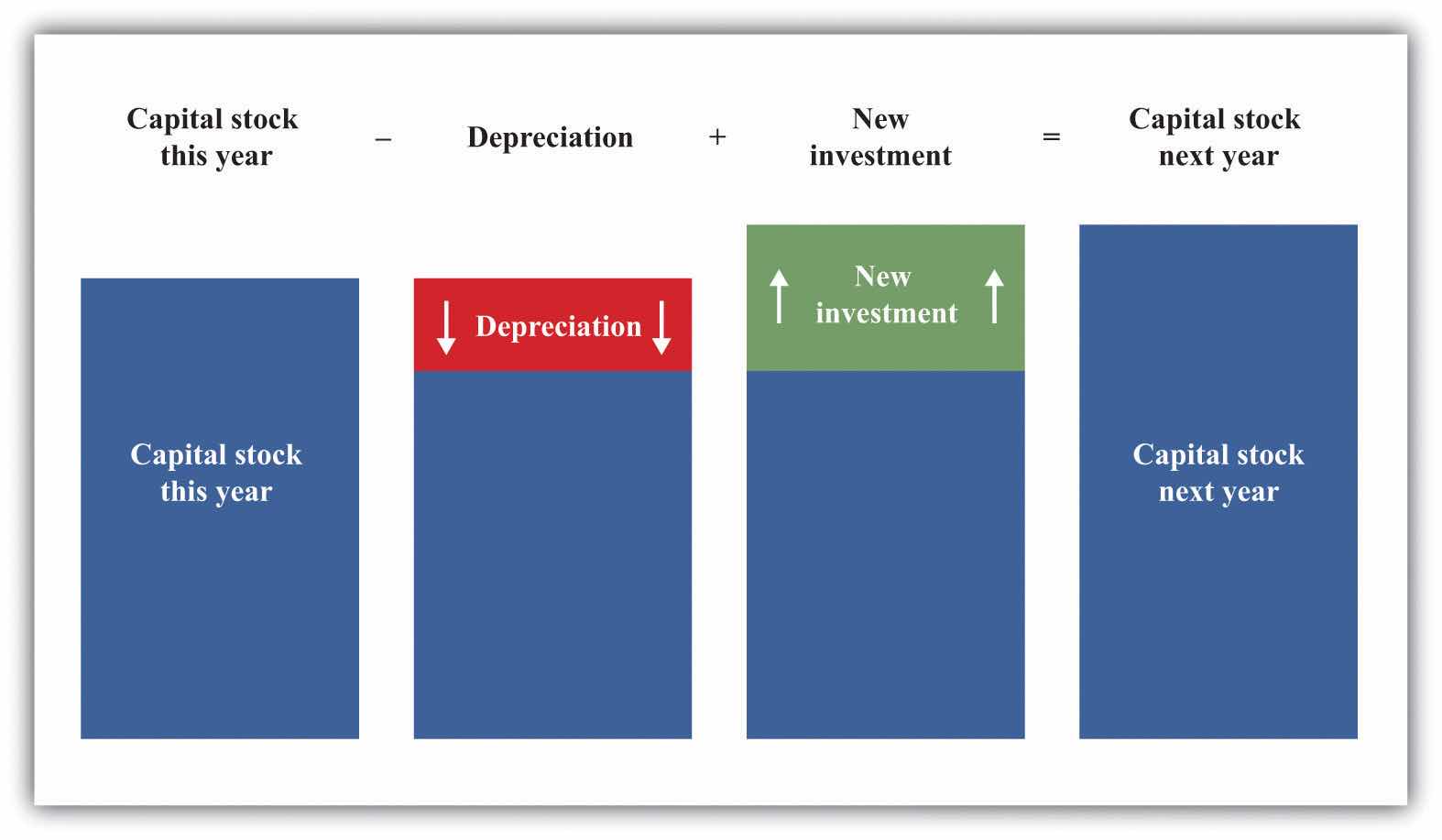

The overall capital stock increases if there is enough investment to replace the worn out capital and still contribute some extra. The overall change in the capital stock is equal to new investment minus depreciation:

change in capital stock = investment − depreciation of existing capital stock.Investment and depreciation are the flows that lead to changes in the stock of physical capital over time. We show this schematically in Figure 20.9 "The Accumulation of Capital". Notice that capital stock could actually become smaller from one year to the next, if investment were insufficient to cover the depreciation of existing capital.

Figure 20.9 The Accumulation of Capital

Every year, some capital stock is lost to depreciation, as buildings fall down and machines break down. Each year there is also investment in new capital goods.

Can physical capital move from place to place? A first guess might be no. Although some capital goods, such as computers, can be transported, most capital goods are fixed in place. Factories are not easily moved from one place to another.

New capital, however, can be located anywhere. When Toyota decides to build a new factory, it could put it in Japan, the United States, Italy, Vietnam, or Brazil. Even if existing capital stocks are not very mobile, investment is. In the long run, firms can decide to close operations in one country and open in another. To understand how much capital a country has, therefore, we must recognize that investment in one country may come from elsewhere in the world.

Just as workers go in search of high wages, so the owners of capital seek to find the places where capital will have the highest return. We already know that the real wage is a measure of the marginal product of labor. Similarly, the real return on investment is the marginal product of capital (more precisely, the marginal product of capital adjusted for depreciation). Remember that the marginal product of capital is defined as the amount of extra output generated by an extra unit of capital. The owners of capital look to put their capital in countries where its marginal product is high.

Earlier, we saw two reasons why the marginal product of labor (and thus the real wage) might be higher in one country rather than another. There are likewise two reasons why the marginal product of capital might be higher in one country (A) rather than in another country (B). Holding all else the same, the marginal product of capital will be higher in country A if

These two factors determine the return on investment in a country. The benefits of acquiring more capital are higher in a country that has relatively little capital than in a country that has a lot of capital. This is because new capital can be allocated to projects that yield a lot of extra output, but as the country acquires more and more capital, such projects become harder and harder to find. Conversely, a country that has more of the other inputs in the production function will have a higher marginal product of capital.

Countries with a lot of labor, other things being equal, will be able to get more out of a given piece of machinery—because each piece of machinery can be combined with more labor time. As a simple example, think about taxis. In a capital-rich country, there may be only one driver for every taxi. In a poorer country, two or three drivers often share a single vehicle, so that vehicle spends much more time on the road. The return on capital—other things being equal—is higher in countries with a lot of labor and not very much capital to share around. Such countries are typically relatively poor, suggesting that poor countries should attract investment funds from elsewhere. In other words, basic economics suggests that if the return on investment is indeed higher in poor countries, investment funds should flow to those countries.

We certainly do see individual examples of such flows. The story at the beginning of this chapter about a Taiwanese company establishing a factory in Vietnam is one example. The following quotation from a British trade publication describes another.

Less than two months into 2006 and the UK’s grocery manufacturing industry is already notching up a growing list of casualties: Leaf UK is considering whether to close its factory in Stockport; Elizabeth Shaw is shutting a plant in Bristol; Arla Foods UK is pulling out of a site at Uckfield; Richmond Foods is ending production in Bude; and Hill Station is shutting a site in Cheadle.

[…]

The stories behind these closures are all very different. But two common trends emerge. First, suppliers are being forced to step up the pace of consolidation as retailer power grows and that means more facilities are being rationalised. Second, production is being shifted offshore as grocery suppliers take advantage of lower-cost facilities.“Shutting Up Shop,” The Grocer, February 25, 2006, accessed June 28, 2011, http://www.coadc.com/grt_article_6.htm. The Grocer is a trade publication for the grocery industry in the United Kingdom.

This excerpt observes that food processing that used to be carried out in Britain is being shifted to poorer Eastern European countries, such as Poland. When factories close in Britain and open in Poland, it is as if physical capital—factories and machines—is moving from Britain to other countries.

If the amount of capital (relative to labor) were the only factor determining investment, we would expect to see massive amounts of lending going from rich countries to poor countries. Yet we do not see this. The rich United States, in fact, borrows substantially from other countries. The stock of other inputs—human capital, knowledge, social infrastructure, and natural resources—also matters. If workers are more skilled (possess more human capital) or if an economy has superior social infrastructure, it can obtain more output from a given amount of physical capital. The fact that the United States has more of these inputs helps to explain why investors perceive the marginal product of capital to be high in the United States.

Earlier we explained that even though migration could in principle even out wages in different economies, labor is, in fact, not very mobile across national boundaries. Capital is relatively mobile, however, and the mobility of capital will also tend to equalize wages. If young Polish workers move from Poland to England, real wages will tend to increase in Poland and decrease in England. If grocery manufacturers move production from England to Poland, then real wages will likewise tend to increase in Poland and decrease in England.

In fact, imagine that two countries have different amounts of physical capital and labor, but the same amount of all other inputs. If physical capital moves freely to where it earns the highest return, then both countries will end up with the same marginal product of capital and the same marginal product of labor. The movement of capital substitutes for labor migration and leads to the same result of equal real wages. This is a striking result.

The result is only this stark if the two countries have identical human capital, knowledge, social infrastructure, and natural resources.There are, not surprisingly, other, more technical, assumptions that matter as well. Perhaps the most important is that the production function should indeed display diminishing marginal product of capital, as we have assumed in this chapter. If other inputs differ, then the mobility of capital will still affect wages, but wages will remain higher in the economy with more of other inputs. If workers in one country have higher human capital, then they will earn higher wages even if capital can flow freely between countries. But the underlying message is the same: globalization, be it in the form of people migrating from one country to another or capital moving across national borders, should tend to make the world a more equal place.