This is “Rational Expectations”, section 26.1 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.0).

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. You may also download a PDF copy of this book (8 MB) or just this chapter (310 KB), suitable for printing or most e-readers, or a .zip file containing this book's HTML files (for use in a web browser offline).

26.1 Rational Expectations

Learning Objectives

- How does the new classical macroeconomic model differ from the standard, pre-Lucas AS-AD model?

- What does the new classical macroeconomic model suggest regarding the efficacy of activist monetary policy? Why?

It turns out that the theory of rational expectations we learned about in Chapter 7 "Rational Expectations, Efficient Markets, and the Valuation of Corporate Equities" has important implications for monetary policy. In a quest to understand why policymakers had such a poor record, especially during the 1970s, Len Mirman (University of Virginia),http://www.virginia.edu/economics/mirman.htm Robert Lucas (University of Chicago),http://home.uchicago.edu/~sogrodow/ Thomas Sargent (New York University),http://homepages.nyu.edu/~ts43/ Bennett McCallum (Carnegie-Mellon),http://public.tepper.cmu.edu/facultydirectory/FacultyDirectoryProfile.aspx?ID=96 Edward Prescott (Arizona State),http://www.minneapolisfed.org/research/prescott/ and other economists of the so-called expectations revolution discovered that expansionary monetary policies cannot be effective if economic agents expect them to be implemented. Conversely, to thwart inflation as quickly and painlessly as possible, the central bank must be able to make a credible commitment to stop it. In other words, it must convince people that it can and will stop prices from rising.

Stop and Think Box

During the American Revolution, the Continental Congress announced that it would stop printing bills of credit, the major form of money in the economy since 1775–1776, when rebel governments (the Continental Congress and state governments) began financing their little revolution by printing money. The Continental Congress implemented no other policy changes, so everyone knew that its large budget deficits would continue. Prices continued upward. Why?

The Continental Congress did not make a credible commitment to end inflation because its announcement did nothing to end its large and chronic budget deficit. It also did nothing to prevent the states from issuing more bills of credit.

Lucas was among the first to highlight the importance of public expectations in macroeconomic forecasting and policymaking. What matters, he argued, was not what policymakers’ models said would happen but what economic agents (people, firms, governments) believed would occur. So in one instance, a rise in the fed funds rate might cause long-term interest rates to barely budge, but in another it might cause them to soar. In short, policymakers can’t be certain of the effects of their policies before implementing them.

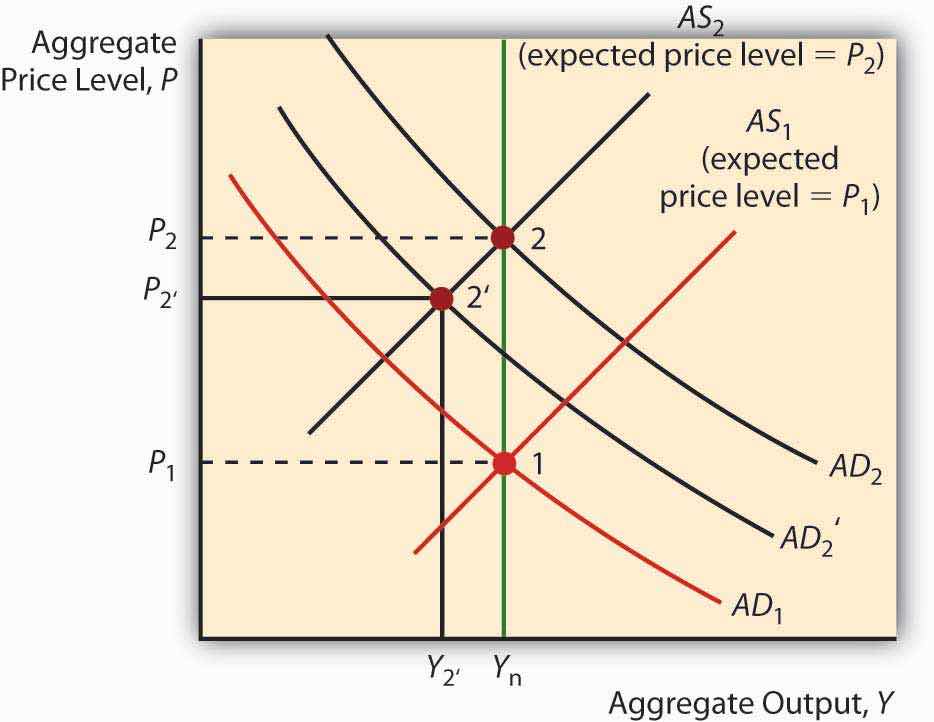

Because Keynesian cross diagrams and the IS-LM and AS-AD models did not explicitly take rational expectations into account, Lucas, Sargent, and others had to recast them in what is generally called the new classical macroeconomic model. That new model uses the AS, ASL, and AD curves but reduces the short run to zero if the policy is expected. So, for example, an anticipated EMP shifts AD right but immediately shifts AS left as workers spontaneously push for higher wages. The price level rises, but output doesn’t budge. An unanticipated EMP, by contrast, has the same effect as described in earlier chapters—a temporary (but who knows how long?) increase in output (and a rise in P followed by another when the AS curve eventually shifts left).

Now get this: Y* can actually decline if an EMP is not as expansionary as expected! If economic actors expect a big shift in AD, the AS curve will shift hard left to keep Y* at Ynrl, as in Figure 26.1 "The effect of an unexpectedly weak EMP". If the AD curve does not shift as far right as expected, or indeed if it stays put, prices will rise and output will fall, as in the following graph. This helps to explain why financial markets sometimes react badly to small decreases in the Fed’s fed funds target. They expected more!

Figure 26.1 The effect of an unexpectedly weak EMP

What this means for policymakers is that they have to know not only how the economy works, which is difficult enough, they also have to know the expectations of economic agents. Figuring out what those expectations are is quite difficult because economic agents are numerous and often have conflicting expectations, and weighting them by their importance is super-duper-tough. And that is at T1. At T2, nanoseconds from now, expectations may be very different.

Key Takeaways

- The new classical macroeconomic model takes the theory of rational expectations into account, essentially driving the short run to zero when economic actors successfully predict policy implementation.

- The new classical macroeconomic model draws the efficacy of EMP or expansionary fiscal policy (EFP) into serious doubt because if market participants anticipate it, the AS curve will immediately shift left (workers will demand higher wages and suppliers will demand higher prices in anticipation of inflation), keeping output at Ynrl but moving prices significantly higher.

- Stabilization (limiting fluctuations in Y*) is also difficult because policymakers cannot know with certainty what the public’s expectations are at every given moment.

- The good news is that the model suggests that inflation can be ended immediately without putting the economy into recession (decreasing Y*) if policymakers (central bankers and those in charge of the government’s budget) can credibly commit to squelching it.

- That is because workers and others will stop pushing the AS curve to the left as soon as they believe that prices will stay put.