This is “Innovations Galore”, section 10.2 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.0).

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. You may also download a PDF copy of this book (8 MB) or just this chapter (835 KB), suitable for printing or most e-readers, or a .zip file containing this book's HTML files (for use in a web browser offline).

10.2 Innovations Galore

Learning Objective

- Why did the Great Inflation spur financial innovation?

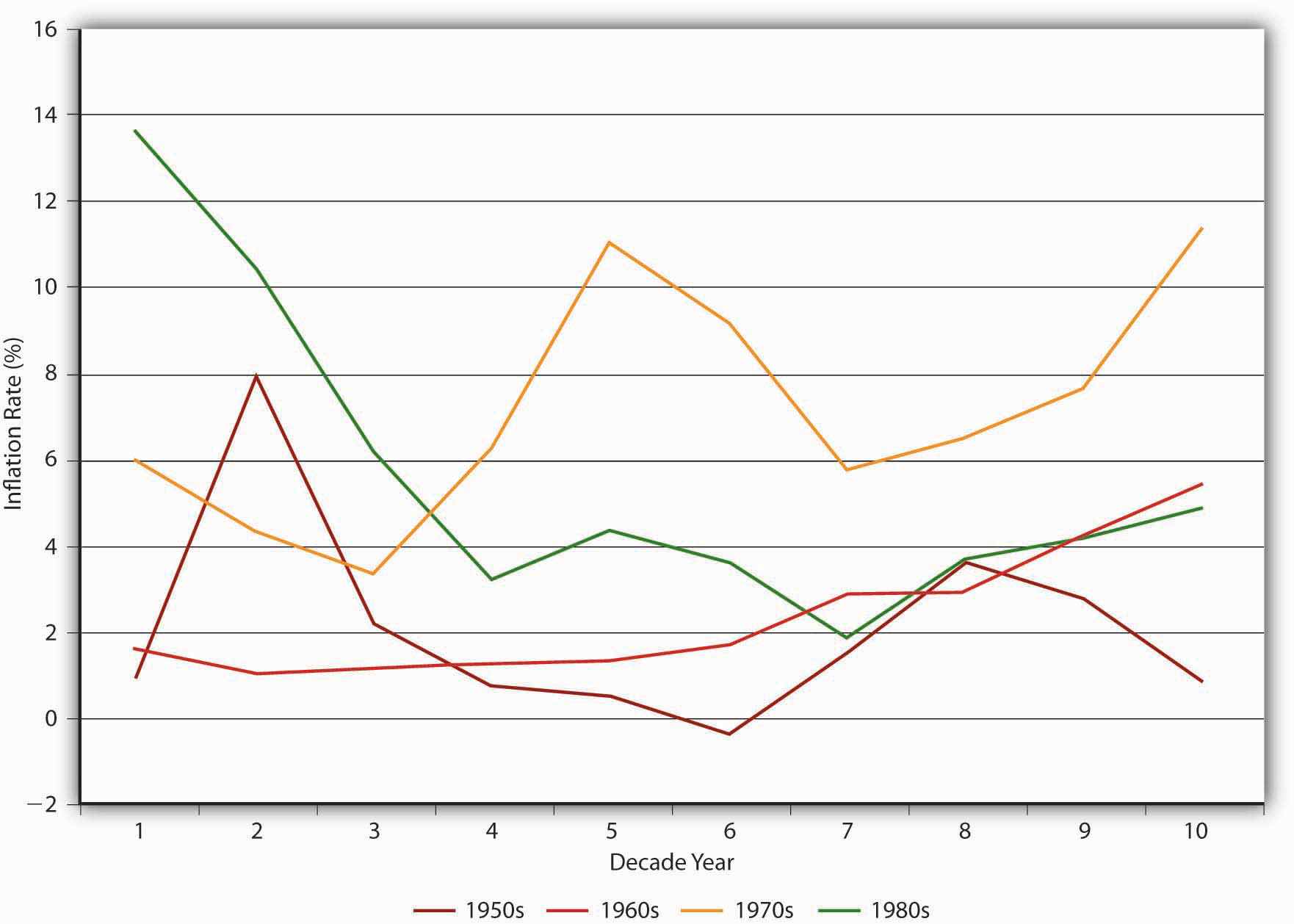

Competition also drives bankers to adopt new technologies and search for ways to reduce the negative effects of volatility. It is not surprising, therefore, that as the U.S. financial system grew more competitive in the 1970s and 1980s, a time of unprecedented macroeconomic volatility, the pace of financial innovation increased dramatically. As Figure 10.1 "U.S. inflation rates, 1950–1989" shows, beginning in the late 1960s, inflation rose steadily and grew increasingly erratic. Not surprisingly, nominal interest rates rose as well, via the Fisher Equation. As we saw in Chapter 9 "Bank Management", interest rate risk, particularly rising interest rates, is one of the things that keeps bankers awake at night. They could not have slept much during the Great Inflation of 1968 to 1982, when the aggregate price level rose over 110 percent all told, more than any fifteen-year period before or since.

Figure 10.1 U.S. inflation rates, 1950–1989

Bankers responded to the increased interest rate risk by inducing others to assume it. As discussed in Chapter 9 "Bank Management", bankers can use financial derivatives, like options, futures, and swaps, to hedge their interest rate risks. It is no coincidence that the modern revival of such markets occurred during the 1970s. Also in the 1970s, bankers began to make adjustable-rate mortgage loans. Traditionally, mortgages had been fixed rate. The borrower promised to pay, say, 6 percent over the entire fifteen-, twenty-, or thirty-year term of the loan. As we saw in Chapter 9 "Bank Management", fixed-rate loans were great for banks when interest rates declined (or stayed the same). But when rates rose, banks got stuck with long-term assets that earned well below what they had to pay for their short-term liabilities. One solution was to get borrowers to take on the risk by inducing them to promise to pay some market rate, like the six-month Treasury rate, plus 2, 3, 4, or 5 percent. That way, when interest rates rise, the borrower has to pay more to the bank, helping it with its gap problem. Of course, when rates decrease, the borrower pays less to the bank. The key is to realize that with adjustable-rate loans, interest rate risk, as well as reward, falls on the borrower, rather than the bank. To induce borrowers to take on that risk, banks must offer them a more attractive (lower) interest rate than on fixed-rate mortgages. Fixed-rate mortgages remain popular, however, because many people don’t like the risk of possibly paying higher rates in the future. Furthermore, if their mortgages contain no prepayment penalty clause (and most don’t), borrowers know that they can take advantage of lower interest rates by refinancing—getting a new loan at the current, lower rate and using the proceeds to pay off the higher-rate loan. Due to the high transaction costs (“closing costs” like loan application fees, appraisal costs, title insurance, and so forth) associated with home mortgage re-fis, however, interest rates must decline more than a little bit before it is worthwhile to do one.http://www.bankrate.com/brm/calc_vml/refi/refi.asp

Stop and Think Box

In the 1970s and 1980s, life insurance companies sought regulatory approval for a number of innovations, including adjustable-rate policy loans and variable annuities. Why? Hint: Policy loans are loans that whole life insurance policyholders can take out against the cash value of their policies. Most policies stipulated a 5 or 6 percent fixed rate. Annuities, annual payments made during the life of the annuitant, were also traditionally fixed.

Life insurance companies, like banks, were adversely affected by disintermediation during the Great Inflation. Policyholders astutely borrowed the cash values of their life insurance policies at 5 or 6 percent, then re-lent the money at the going market rate, which was often in the double digits. By making the policy loans variable, life insurers could adjust them upward when rates increased to limit such arbitrage. Similarly, fixed annuities were a difficult sell during the Great Inflation because annuitants saw the real value (the purchasing power) of their annual payments decrease dramatically. By promising to pay annuitants more when interest rates and inflation were high, variable-rate annuities helped insurers to attract customers.

Key Takeaways

- By increasing macroeconomic instability, nominal interest rates, and competition between banks and financial markets, the Great Inflation forced bankers and other financiers to innovate.

- Bankers innovated by introducing new products, like adjustable-rate mortgages and sweep accounts; new techniques, like derivatives and other off-balance-sheet activities; and new technologies, including credit card payment systems and automated and online banking facilities.