Mindful Meditation and the Brain by Shauna Shapiro [6 min]

How Meditation Can Reshape Our Brains by Sara Lazar [8 min]

Why a Neuroscientist Would Study Meditation by Willoughby Britton [10 min]

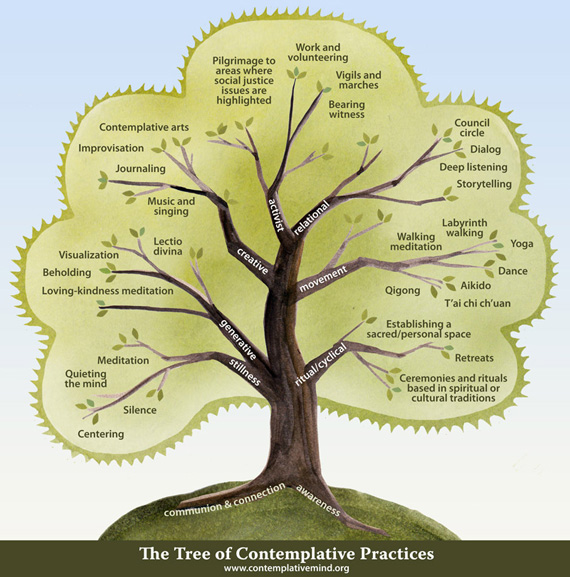

There are so many questions one could ask about practice: What does it mean to “practice” mindfulness? Is it necessary to practice in a formal way, such as sitting meditation or yoga? If one is going to have a formal practice, then how long and how often? Or is it enough to let the practice opportunities come spontaneously, such as remembering to pause (STOP) at a tense moment, or fully experiencing your surroundings in the middle of a busy day? These are not questions anyone else can answer for us – each of us must find our own way to renew or maintain mindfulness in our lives, one that resonates with who we are. This is a continual journey, one that is a practice in itself. There are countless ways to practice mindfulness, as Miribai Bush's Tree of Contemplative Practices illustrates:

When mindfulness is cultivated intentionally, it is sometimes referred to as deliberate mindfulness. When it is available to us spontaneously, as it tends to be more and more, the more it is cultivated intentionally, it is sometimes referred to as effortless mindfulness…

- Jon Kabat-Zinn, Arriving at Your Own Door: 108 Lessons in Mindfulness

For those seeking balance in their lives, a certain flexibility of approach is not only helpful, it is essential. It is important to know that meditation has little to do with dock time. Five minutes of formal practice can be as profound or more so than forty-five minutes. The sincerity of your effort matters far more than elapsed time, since we are really talking about stepping out of minutes and hours and into moments, which are truly dimensionless and therefore infinite.

So, if you have some motivation to practice even a little, that is what is important. Mindfulness needs to be kindled and nurtured, protected from the winds of a busy life or a restless and tormented mind, just as a small flame needs to be sheltered from strong gusts of air. If you can only manage five minutes, or even one minute of mindfulness at first, that is truly wonderful. It means you have already remembered the value of stopping, of shifting even momentarily from doing to being…

Forming the intention to practice and then seizing a moment - any moment - and encountering it fully in your inward and outward posture, lies at the core of mindfulness. Long and short periods of practice are both good, but "long" may never flourish if your frustration and the obstacles in your path loom too large. Far better to adventure into longer periods of practice gradually on your own than never to taste mindfulness or stillness because the perceived obstacles were too great. A journey of a thousand miles really does begin with a single step. When we commit to taking that step - in this case, to taking our seat for even the briefest of times - we can touch the timeless in any moment. From that all benefit flows, and from that alone.

- Jon Kabat-Zinn, Wherever You Go, There You Are

Sticking with a spiritual training requires an ocean of patience because our habit of wanting to be somewhere else is so strong. We've distracted ourselves from the present for so many moments, for so many years, even lifetimes. Here is an accomplishment in The Guinness Book of World Records that I like to note at meditation retreats when people are feeling frustrated. It indicates that the record for persistence in taking and failing a driving test is held by Mrs. Miriam Hargrave of Wakefield, England. Mrs. Hargrave failed her thirty-ninth driving test in April, 1970, when she crashed, driving through a set of red lights. In August of the following year she finally passed her fortieth test. Unfortunately, she could no longer afford to buy a car because she had spent so much on driving lessons. In the same spirit, Mrs. Fanny Turner of Little Rock, Arkansas, passed her written test for a driver's license on her 104th attempt in October 1978. If we can bring such persistence to passing a driving test or mastering the art of skateboarding or anyone of a hundred other endeavors, surely we can also master the art of connecting with ourselves. As human beings we can dedicate ourselves to almost anything, and this heartfelt perseverance and dedication brings spiritual practice alive.

The attitude or spirit with which we do our meditation helps us perhaps more than any other aspect. What is called for is a sense of perseverance and dedication combined with a basic friendliness. We need a willingness to directly relate again and again to what is actually here, with a lightness of heart and sense of humor. We do not want the training of our puppy to become too serious a matter.

- from A Path With Heart by Jack Kornfield