American Expansionism

Manifest destiny was the 19th century U.S. belief that the country (and more specifically, the white Anglo-Saxon race within it) was destined to expand across the continent. Democrats used the term in the 1840s to justify the war with Mexico. The concept was largely denounced by Whigs and fell into disuse after the mid-19th century. Advocates of manifest destiny believed that expansion was not only wise, but that it was readily apparent (manifest) and could not be prevented (destiny).

The concept of U.S. expansionism is in fact much older. It is rooted in European nations' early colonization of the Americas, the establishment of the United States by white Anglo-Saxons from England, and the continued wars against and forced removal of the American Indians indigenous to the lands. In 1845, John L. O’Sullivan, a New York newspaper editor, introduced the concept of “manifest destiny” in the July/August issue of the United States Magazine and Democratic Review, in an article titled, "Annexation." The term described the very popular idea of the special role of the United States in overtaking the continent—the divine right and duty of white Americans to seize and settle the continent's western territory, thus spreading Protestant, democratic values.

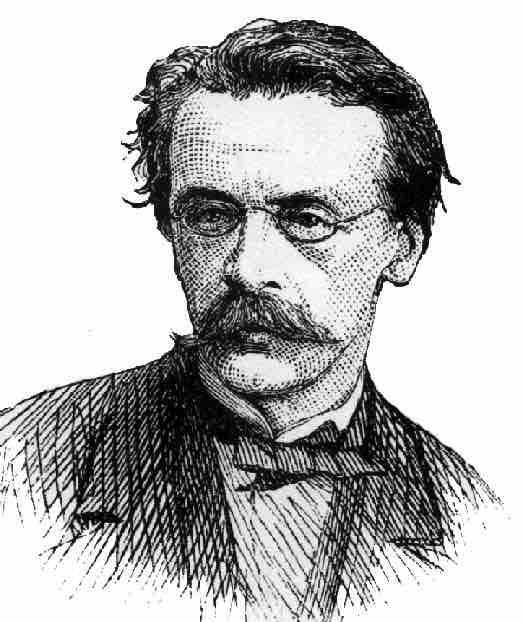

Sketch of John L. O'Sullivan, 1874

John L. O'Sullivan was an influential columnist as a young man, but is now generally remembered only for his use of the phrase "manifest destiny" to advocate the annexation of Texas and Oregon.

Manifest Destiny and Politics

In this climate of opinion, voters in 1844 elected into the presidency James K. Polk, a slaveholder from Tennessee, because he vowed to annex Texas as a new slave state, and to take Oregon. "Manifest destiny" was a term Democrats primarily used to support the Polk Administration's expansion plans. The idea of expansion was also supported by Whigs like Henry Clay, Daniel Webster, and Abraham Lincoln, who wanted to expand the nation's economy. John C. Calhoun was a notable Democrat who generally opposed his party on the issue, which fell out of favor by 1860.

Manifest destiny was a general notion rather than a specific policy. The term combined a belief in expansionism with other popular ideas of the era, including US exceptionalism and Romantic nationalism. While many writers have focused on US expansionism when discussing manifest destiny, others see in the term a broader expression of a belief in the United States' "mission" in the world, which has meant different things to different people over the years. For example, the belief in an U.S. mission to promote and defend democracy throughout the world, as expounded by Lincoln and Woodrow Wilson, continues to influence US political ideology to this day.

The angel Columbia was an image commonly used at the time to personify the United States. Originating from the name of Christopher Columbus, it was originally used for the 13 colonies and remained the dominant image for the female personification of the United States until the Statue of Liberty displaced it in the 1920s. During the era of manifest destiny, many images were produced of Columbia spreading democracy and other United States values across the western lands.

The Angel Columbia

This 1872 painting depicts Columbia as the "Spirit of the Frontier," carrying telegraph lines across the western frontier to fulfill manifest destiny.