American Involvement in Latin America

During the Johnson Administration, the United States intervened in domestic political conflicts in Latin and South American countries. American interventions in the Brazilian coup d'état of 1964 and the Dominican Civil War of 1965 are two notable examples. In both cases, the Johnson administration, wanting to prevent the rise to power of another Fidel Castro in the western hemisphere, chose to provide military support to one side of the conflict. These events were largely overshadowed by the Vietnam War and are not as frequently studied today.

Both events were strongly influenced by United States interest in maintaining its position as a world superpower. In order to do this, leaders of the United States felt it necessary to prevent the spread of communism and support—or manipulate into existence—democratic and capitalist governments in nations around the world. By using U.S. armed forces in Brazil and in the Dominican Republic to overthrow communist and socialist leadership and institute governments that were more favorable to the U.S., Johnson's administration continued a long legacy of United States control in foreign affairs.

The 1964 Brazilian coup d'état

The 1964 Brazilian coup d'état was a series of events that occurred in Brazil on March 31, 1964, that culminated with the overthrow of President João Goulart by the U.S. Armed Forces on April 1. The coup put an end to the government of Goulart, who was also known as Jango, a member of the Brazilian Labor Party. He was democratically elected Vice President by the people of Brazil in the same election that elected conservative Jânio Quadros. Goulart was from the National Labor Party and backed by the National Democratic Union to the presidency.

Quadros resigned in 1961, the same year of his inauguration, in a clumsy political maneuver to increase his popularity. According to the constitution then in force, Goulart should have automatically replaced Quadros as president, but he was away on a diplomatic trip. A moderate nationalist, Goulart was accused of being a communist by right-wing militants and was unable to take office. After a long negotiation led mainly by Goulart's brother-in-law Leonel Brizola, Goulart's supporters and the right-wing reached an agreement under which the parliamentary system would replace the presidential system in the country, and Goulart would be named head of state.

In 1963, however, Goulart successfully re-established the presidential system through a referendum. He finally took office as president with full powers, and during his rule, several structural problems in Brazilian politics became evident, as well as disputes in the context of the Cold War, which helped destabilize his government. His Basic Reforms Plan, which aimed at socializing the profits of large companies toward ensuring a better quality of life for most Brazilians, was labeled as a socialist threat by both the U.S. military and right-wing sectors of Brazilian society, which organized major demonstrations against the government in the Marches of the Family with God for Freedom.

The U.S.-backed coup successfully removed Goulart from office and subjected Brazil to a military regime, politically aligned to the interests of the United States government. The U.S. ambassador at the time and the military attaché kept in constant contact with President Lyndon Johnson as the crisis progressed. Johnson urged taking "every step that we can" to support the overthrow of João Goulart, helping the Brazilian military authorities against the left-winged Goulart government. The military regime that replaced Goulart would last until 1985, when Tancredo Neves would be indirectly elected the first civilian president of Brazil since the 1960 elections.

United States Occupation of the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Civil War of 1965 was the second time the United States occupied the Dominican Republic. It began when the U.S. Marine Corps entered Santo Domingo on April 28, 1965 and ended in September of 1966. The coup d'état and civil war in the Dominican Republic was rooted in the election of Juan Bosch as president in 1962, following a period of political instability after the assassination of long-time dictator Rafael Trujillo in 1961. Opposition groups, known as Loyalists, launched a military coup d'état in 1963, effectively negating the 1962 elections by installing a civilian junta dominated by former members of the Trujillo regime and headed by Donald Reid Cabral, an American-educated businessman. Constitutionalists supported the return of Bosch, and widespread dissatisfaction produced a revolution on May 16.

U.S. President Johnson, siding with the Loyalists and convinced that the defeat of the Loyalist forces would create "a second Cuba" on America's doorstep, ordered a military intervention. All civilian advisers had recommended against immediate intervention, hoping that the Loyalist side could bring an end to the civil war on their own. President Johnson, however, ordered 42,000 soldiers and marines to the Dominican Republic. By April 29, 1966, a cease-fire was negotiated, and on May 5 the Act of Santo Domingo was signed by Colonel Benoit (a Loyalist), Colonel Caamaño (a Constitutionalist) and the Organization of American States (OAS) Special Committee. Backed by the United States, General Imbert, a Loyalist, became president of the Government of National Reconstruction. Further manipulation from U.S. military operations consolidated the Loyalist control of the government. The U.S. gradually began removing troops, turning policing and peacekeeping operations over to Brazilian troops. In democratic elections in 1966, Joaquín Balaguer was elected and enjoyed the overt support of the Johnson administration. While a group of new millionaires flourished during Balaguer's administrations, supported by U.S investments, the overall poverty rate of the country increased dramatically.

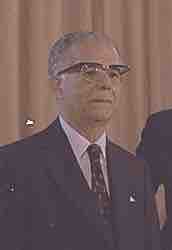

Joaquin Balaguer, 1977

After the Coup of 1965, Jaquin Balaguer became president of the Dominican Republic.