Counterculture in Literature: Underground Press in the 1960s

In the U.S., the term "underground newspaper" generally refers to an independent newspaper focusing on unpopular themes or counterculture issues. Typically, these tend to be politically to the left or far left. The term most often refers to publications of the period 1965-1973, when an underground newspaper craze swept the country. These publications became the voice of the rising New Left and the hippie/psychedelic/rock and roll counterculture of the 1960s in America; they were also a focal point of opposition to the Vietnam War and the draft. Underground newspapers sprang up in most cities and college towns, serving to define and communicate the range of phenomena that defined the counterculture: radical political opposition to "The Establishment"; colorful experimental (and often explicitly drug-influenced) approaches to art, music, and cinema; and uninhibited indulgence in sex and drugs as a symbol of freedom.

The boom in the underground press was made practical by the availability of cheap offset printing, which made it possible to print a few thousand copies of a small tabloid paper for a few hundred dollars. Paper was cheap, and many printing firms around the country had over-expanded during the 1950s, leaving them with excess capacity on their offset web presses, which could be negotiated at bargain rates.

One of the first underground newspapers of the 1960s was the Los Angeles Free Press, founded in 1964 and first published in 1965. The Rag, founded in Austin, Texas in 1966, was an especially influential underground newspaper as, according to historian Abe Peck, it was the "first undergrounder to represent the participatory democracy, community organizing and synthesis of politics and culture that the New Left of the midsixties was trying to develop."

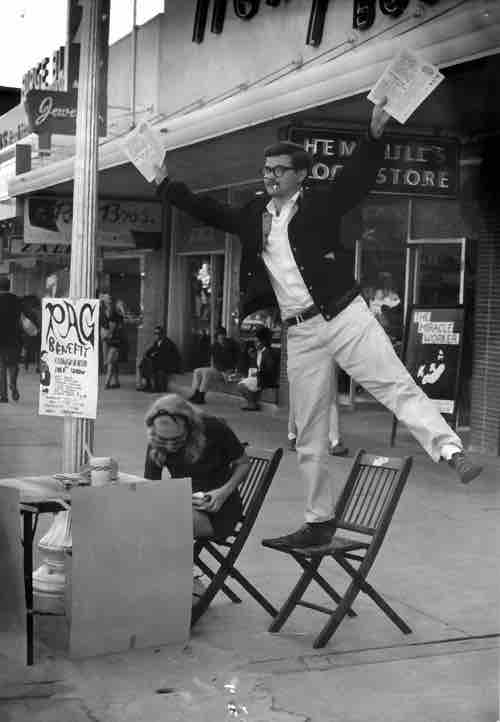

The Rag

A Rag staffer selling the newspaper in Austin, Texas, in 1966.

The Underground Press Syndicate

In mid-1966, the cooperative Underground Press Syndicate (UPS) was formed. The UPS allowed member papers to freely reprint content from any of the other member papers. By 1969, virtually every sizable city or college town in North America boasted at least one underground newspaper. During the peak years of the underground press phenomenon, about 100 papers were publishing at any given time. A UPS roster published in November 1966 listed 14 underground papers, 11 of them in the United States.

Underground Papers in the Military

There also existed an underground press network within the U.S. military. The GI underground press produced a few hundred titles during the Vietnam War. Some were produced by anti-war GI coffeehouses, and many of them were small, crudely produced, and low-circulation papers. Three or four GI underground papers had large-scale, national distribution of more than 20,000 copies, including thousands of copies mailed to GIs overseas. These papers were produced with the support of civilian anti-war activists and had to be disguised to be sent through the mail into Vietnam. Soldiers distributing or even possessing them might be subject to harassment, disciplinary action, or arrest.

Many of the papers faced official harassment on a regular basis; local police repeatedly raided offices, charged editors or writers with drug charges or obscenity, arrested street vendors, and pressured local printers not to print underground papers.

The Beat Generation

The Beat Generation was a group of American post-World War II writers who came to prominence in the 1950s, including the cultural phenomena they documented and inspired. Central elements of Beat culture included the experimentation with drugs, alternative forms of sexuality, interest in Eastern religion (such as Buddhism), rejection of materialism, and idealizing exuberant means of expression and being.

Allen Ginsberg's Howl (1956), William S. Burroughs's Naked Lunch (1959), and Jack Kerouac's On the Road (1957) are among the best known examples of Beat literature. Both Howl and Naked Lunch became the focus of obscenity trials. The publishers won the trials, however, and publishing in the United States became more liberalized. The members of the Beat Generation developed a reputation as new bohemian hedonists who celebrated non-conformity and spontaneous creativity.

Origin of the Beats

Jack Kerouac introduced the phrase "Beat Generation" in 1948 to characterize a perceived underground, anti-conformist youth movement in New York. The adjective "beat" could colloquially mean tired or beaten down, but Kerouac expanded the meaning to include the connotations upbeat, beatific, and the musical association of being on the beat.

The origins of the Beat Generation can be traced to Columbia University when Kerouac, Ginsberg, Lucien Carr, Hal Chase, and others first met. Classmates Carr and Ginsberg discussed the need for a new vision to counteract what they perceived as their teachers' conservative, formalistic literary ideals. Later, in the mid-1950s, the central figures of the Beat Generation (with the exception of Burroughs) ended up living in San Francisco together.

Beatniks and the Beat Generation

The term "Beatnik" was coined to represent the Beat Generation and was a play on words referring to both the name of the recent Russian satellite, Sputnik, and the Beat Generation. The term suggested that beatniks were far out of the mainstream of society and possibly pro-Communist. The beatnik term stuck and became the popular label associated with a new stereotype and even caricature of the Beats. While some of the original Beats embraced the beatnik identity, or at least found the parodies humorous (Ginsberg, for example, appreciated the parody), others criticized the beatniks as inauthentic posers. Kerouac feared that the spiritual aspect of his message had been lost and that many were using the Beat Generation as an excuse to be senselessly wild.

The Beat Generation Lifestyle

The original members of the Beat Generation experimented with a number of different drugs, from alcohol and marijuana to LSD and peyote. Many were inspired by intellectual interest, believing these drugs could enhance creativity, insight, and productivity. Many of the key Beat Generation figures were openly homosexual or bisexual, including two of the most prominent writers, Ginsberg and Burroughs. Both Ginsberg's Howl and Burroughs' Naked Lunch contain explicit homosexuality, sexual content, and drug use.

The Beats' Influences on Western Culture

The phenomenon of the Beat Generation had a pervasive influence on Western culture. It was influenced by, and in turn influenced, the sexual revolution, issues around censorship, the demystification of cannabis and other drugs, the musical evolution of rock and roll, the spread of ecological consciousness, and opposition to the military-industrial machine civilization.

The End of the Beats and the Beginning of the Hippies

The 1950s Beat movement beliefs and ideologies metamorphosed into the counterculture of the 1960s, accompanied by a shift in terminology from "beatnik" to "hippie". Many of the original Beats remained active participants, notably Allen Ginsberg, who became a fixture of the anti-war movement. Notably, however, Jack Kerouac broke with Ginsberg and criticized the politically radical protest movements of the 1960s as an excuse to be spiteful.

There were stylistic differences between beatniks and hippies—for example, somber colors, dark sunglasses, and goatees gave way to colorful psychedelic clothing and long hair. The beats were known for playing it cool (keeping a low profile), but the hippies became known for being cool (displaying their individuality). Beyond style, there were also changes in substance: the Beats tended to be essentially apolitical, but the hippies became actively engaged with the civil rights and anti-war movements.

Counterculture in Theatre

Musical theatre in the 1960s started to diverge from the relatively narrow confines of the 1950s. For example, rock music was used in several Broadway musicals. This trend began with the musical "Hair," which featured not only rock music, but also nudity and controversial opinions about the Vietnam War, race relations, and other social issues. "Hair" is often said to be a product of the hippie counterculture and sexual revolution of the 1960s.

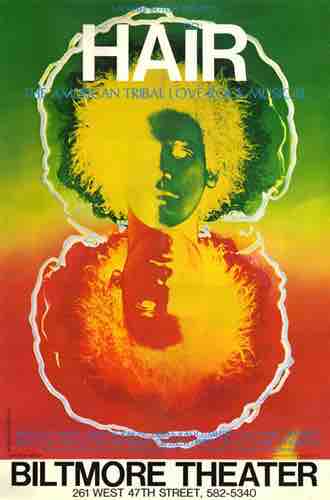

"Hair" the Musical

Attributes of the counterculture were reflected in theatrical productions of the time, for example in the Broadway musical "Hair." Note the elements of psychedelic art in this particular poster.

As the struggle for minorities' civil rights progressed, musical writers were emboldened to write more musicals and operas which aimed to expand mainstream societal tolerance and urged racial harmony. Early works that focused on racial tolerance, though now recognized to have many problematic elements, included "Finian's Rainbow," "South Pacific," and "The King and I." The musical "West Side Story" also spoke a message of racial tolerance. Later on, several shows tackled Jewish subjects and issues, such as "Fiddler on the Roof." By the end of the 1960s, musicals became racially integrated, with black and white cast members even covering each others' roles.

Counterculture in Film

Like newspapers, literature, and theatre, the cinema of the time also reflected the attributes of the counterculture. Dennis Hopper's "Easy Rider" (1969) focused on the changes happening in the world. The film "Medium Cool" portrayed the 1968 Democratic Convention and Chicago police riots, which has led to it being labeled as "a fusion of cinema-vérité and political radicalism." One studio attempt to cash in on the hippie trend was the 1968 film "Psych-Out," which portrayed the hippie lifestyle. The music of the era was represented by films such as 1970's "Woodstock," a documentary of the music festival of the same name.