Women's suffrage in the United States was established over the course of several decades, first in various states and localities, sometimes on a limited basis, and then nationally in 1920.

The demand for women's suffrage began to gather strength in the 1840s, emerging from the broader movement for women's rights. In 1848, the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, passed a resolution in favor of women's suffrage despite opposition from some of its organizers, who believed the idea was too extreme. By the time of the first National Women's Rights Convention in 1850, however, gaining suffrage was becoming an increasingly important aspect of the movement's activities.

The first national suffrage organizations were established in 1869, after the formation of two competing organizations, one led by Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton and the other by Lucy Stone. After years of rivalry, the organizations merged in 1890 as the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA) with Anthony as its leading force.

Hoping the U.S. Supreme Court would rule that women had a constitutional right to vote, suffragists made several attempts to vote in the early 1870s and then filed lawsuits when they were turned away. Anthony actually succeeded in voting in 1872 but was arrested for that act and found guilty in a widely publicized trial that gave the movement fresh momentum. After the Supreme Court ruled against them in 1875, suffragists began the decades-long campaign for an amendment to the U.S. Constitution that would enfranchise women. Much of the movement's energy, however, went toward working for suffrage on a state-by-state basis.

The reform campaigns of the Progressive Era strengthened the suffrage movement. Beginning around 1900, this broad movement began at the grassroots level with such goals as combating corruption in government, eliminating child labor, and protecting workers and consumers. Many of its participants saw women's suffrage as yet another Progressive goal, and they believed that the addition of women to the electorate would help their movement achieve its other goals. In 1912, the Progressive Party, formed by Theodore Roosevelt, endorsed women's suffrage. The burgeoning Socialist movement also aided the drive for women's suffrage in some areas.

In 1916, Alice Paul formed the National Woman's Party (NWP), a militant group focused on the passage of a national suffrage amendment. More than 200 NWP supporters, known as the "Silent Sentinels," were arrested in 1917 while picketing the White House. Some of the protestors went on a hunger strike and endured forced feeding after being sent to prison. Under the leadership of Carrie Chapman Catt, the two-million-member NAWSA also made a national suffrage amendment its top priority. After a hard-fought series of votes in the U.S. Congress and in state legislatures, the Nineteenth Amendment became part of the U.S. Constitution on August 26, 1920. It states, "The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex."

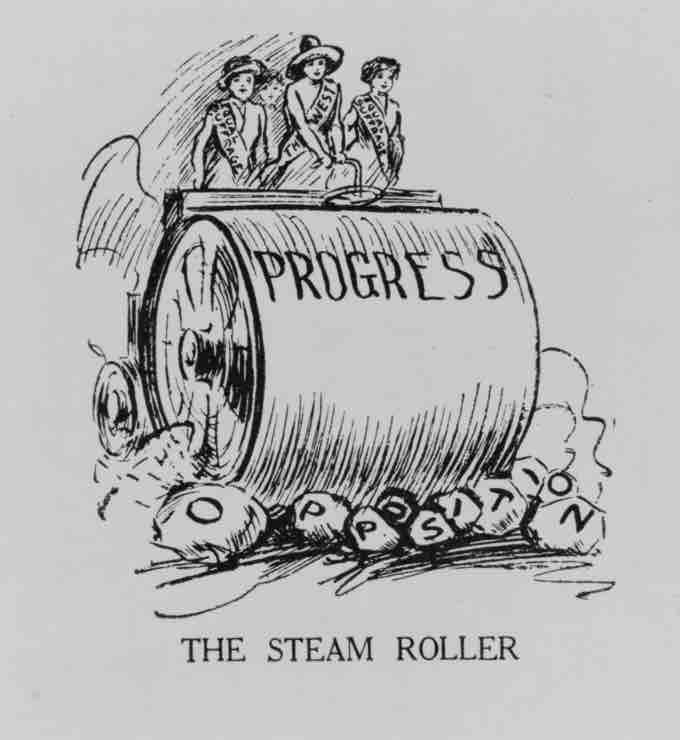

"The Steam Roller"

This political cartoon about suffrage in the United States depicts four women supporting suffrage on a steamroller crushing rocks labeled "opposition."

Opposition

Brewers and distillers, typically rooted in the German-American community, opposed women's suffrage, fearing that women voters would favor the prohibition of alcoholic beverages. German Lutherans and German Catholics typically opposed prohibition and women's suffrage; they favored paternalistic families in which the husband decided the family position on public affairs. Their opposition to women's suffrage was subsequently used as an argument in favor of suffrage when German Americans became pariahs during World War I.

Some other businesses, such as Southern cotton mills, opposed suffrage because they feared that women voters would support the drive to eliminate child labor. Political machines, such as Tammany Hall in New York City, opposed it because they feared that the addition of female voters would dilute the control they had established over groups of male voters.

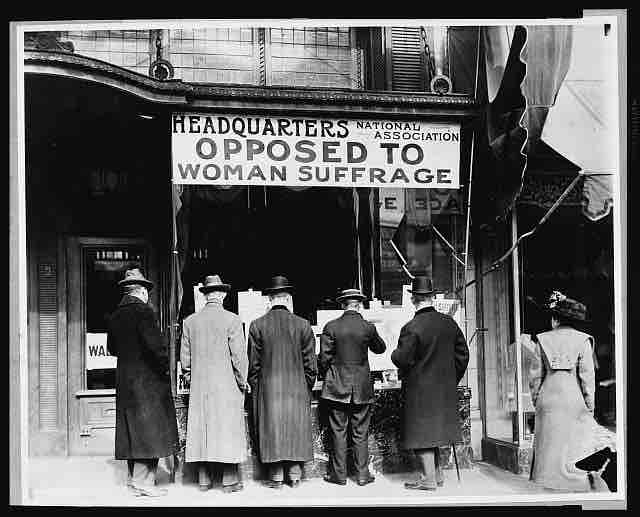

Anti-suffrage forces, initially called the "remonstrants," organized as early as 1870 when the Women's Anti-Suffrage Association of Washington was formed. Widely known as the "antis," they eventually created organizations in some 20 states. In 1911, the National Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage was created. It claimed 350,000 members and opposed women's suffrage, feminism, and socialism. It argued that woman suffrage, "would reduce the special protections and routes of influence available to women, destroy the family, and increase the number of socialist-leaning voters."

Middle- and upper-class anti-suffrage women were conservatives with several motivations. Society women in particular had personal access to powerful politicians, and were reluctant to surrender that advantage. Most often the "antis" believed that politics was dirty and that women's involvement would surrender the moral high ground that women had claimed, and that partisanship would disrupt local club work for civic betterment, as represented by the General Federation of Women's Clubs. The best organized movement was the New York State Association Opposed to Woman Suffrage (NYSAOWS).

Opposed to women's suffrage

Men looking in the window of the National Anti-Suffrage Association headquarters.