Progressive Reform

By the turn of the century, a middle class had developed that was leery of both the business elite and the radical political movements of farmers and laborers in the Midwest and West. The Progressives argued for the need for government regulation of business practices to ensure competition and free enterprise. Congress enacted a law regulating railroads in 1887 (the Interstate Commerce Act), and one preventing large firms from controlling a single industry in 1890 (the Sherman Antitrust Act). These laws were not rigorously enforced, however, until the years between 1900 and 1920, when Republican President Theodore Roosevelt (1901–1909), Democratic President Woodrow Wilson (1913–1921), and others sympathetic to the views of the Progressives came to power. Many of today's U.S. regulatory agencies, including the Interstate Commerce Commission and the Federal Trade Commission, were created during these years

Many Progressives hoped that by regulating large corporations, they could liberate human energies from the restrictions imposed by industrial capitalism. Pro-labor Progressives, such as Samuel Gompers, argued that industrial monopolies were unnatural economic institutions that suppressed the competition that was necessary for progress and improvement. United States antitrust law is the body of laws that prohibits anticompetitive behavior (monopolies) and unfair business practices. Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft supported trust-busting.

Progressives, such as Benjamin Parke De Witt, argued that in a modern economy, large corporations, and even monopolies, were both inevitable and desirable. With their massive resources and economies of scale, large corporations offered the United States advantages that smaller companies could not offer. Yet, these large corporations might abuse their great power. The federal government should allow these companies to exist but should regulate them for the public interest. President Theodore Roosevelt generally supported this idea.

Sherman Act

The Sherman Antitrust Act is a landmark federal statute in the history of U.S. antitrust law passed by Congress in 1890. Passed under the presidency of Benjamin Harrison, the act prohibits certain business activities that federal government regulators deem to be anticompetitive, and requires the federal government to investigate and pursue trusts.

In the general sense, a trust is a centuries-old form of a contract in which one party entrusts its property to a second party. These are commonly used to hold inheritances for the benefit of children, for example. "Trust" in relation to the Sherman Act refers to a type of contract that combines several large businesses for monopolistic purposes (to exert complete control over a market), though the act addresses monopolistic practices even if they have nothing to do with this specific legal arrangement.

The law attempts to prevent the artificial raising of prices by restriction of trade or supply. "Innocent monopoly," or monopoly achieved solely by merit, is perfectly legal, but acts by a monopolist to artificially preserve that status, or nefarious dealings to create a monopoly, are not. The purpose of the Sherman Act is not to protect competitors from harm from legitimately successful businesses, nor to prevent businesses from gaining honest profits from consumers, but rather to preserve a competitive marketplace to protect consumers from abuses.

Trust-busting

Public officials during the Progressive Era put passing and enforcing strong antitrust policies high on their agenda. President Theodore Roosevelt sued 45 companies under the Sherman Act, and William Howard Taft sued 75. In 1902, Roosevelt stopped the formation of the Northern Securities Company, which threatened to monopolize transportation in the Northwest (see Northern Securities Co. v. United States).

One of the most well-known trusts was the Standard Oil Company; John D. Rockefeller in the 1870s and 1880s had used economic threats against competitors and secret rebate deals with railroads to build a monopoly in the oil business, though some minor competitors remained in business. In 1911, the Supreme Court agreed that in recent years (1900–1904) Standard had violated the Sherman Act. It broke the monopoly into three dozen separate competing companies, including Standard Oil of New Jersey (later known as Exxon and now ExxonMobil), Standard Oil of Indiana (Amoco), Standard Oil Company of New York (Mobil, which later merged with Exxon to form ExxonMobil), and so on. In approving the breakup, the Supreme Court added the "rule of reason." Not all big companies, and not all monopolies, are evil; and the courts (not the executive branch) are to make that decision. To be harmful, a trust had to somehow damage the economic environment of its competitors.

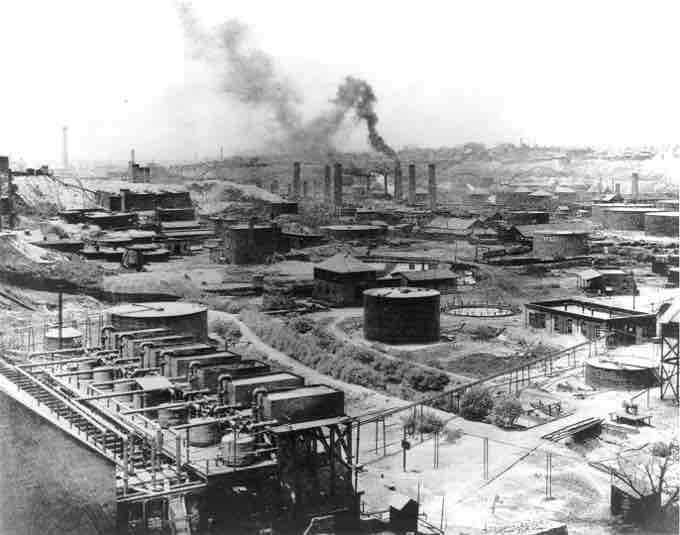

Standard Oil refinery no. 1 in Cleveland, Ohio

Photograph of a Standard Oil refinery. Standard Oil was a major company broken up under U.S. antitrust laws.

Labor Reform

Progressives also enacted laws that regulated businesses to protect workers.

Child-labor laws were designed to prevent the overworking of children in the newly emerging industries. The goal of these laws was to give working-class children the opportunity to go to school and to mature more naturally, thereby liberating the potential and encouraging the advancement of humanity.

After 1907, the American Federation of Labor, under Samuel Gompers, moved to demand legal reforms that would support labor unions. Most of the support came from Democrats, but Theodore Roosevelt and his third party, the Bull Moose Party, also supported such goals as the eight-hour work day, improved safety and health conditions in factories, workers' compensation laws, and minimum-wage laws for women.

In the years between 1889 and 1920, railroad use in the United States expanded sixfold. With this expansion, the dangers to the railroad worker increased. Congress passed the Federal Employers Liability Act (FELA) in response to the high number of railroad deaths in the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century. Under FELA, railroad workers who are not covered by regular workers' compensation laws are able to sue companies over their injury claims. FELA allows monetary payouts for pain and suffering, decided by juries based on comparative negligence rather than pursuant to a predetermined benefits schedule under workers' compensation.

The United States Employees' Compensation Act is a federal law enacted on September 7, 1916. Sponsored by Senator John W. Kern (D) of Indiana and Representative Daniel J. McGillicuddy (D) of Maine, the act established the distribution of compensation to federal civil-service employees for wages lost due to job-related injuries. This act became the precedent for disability insurance across the country and the precursor to broad-coverage health insurance.