BACKGROUND

Like no government initiative before, the New Deal agenda highlighted the issue of the unequal distribution of wealth in the United States. All the major New Deal programs were designed to benefit those in need, including the unemployed, the elderly, the poor, the disabled, or those who kept their jobs yet still struggled to survive (e.g., farmers). However, the New Deal hardly addressed the divisions that had existed in the American society long before the Great Depression. Racial, ethnic, class, and gender inequalities only deepened at the time of the greatest economic crisis of the 20th century and the New Deal did little to address or counteract it. Most New Deal programs targeted generally at Americans, as opposed to those few established to address the needs of specific minority groups, were in fact designed to benefit predominantly white males. While this focus resulted in substantial and welcomed gains for many poor white workers, it produced a mixed outcome for African Americans and working class women. Those who belonged to both of these categories - working class black women - remained the most neglected group of Americans under the New Deal.

AFRICAN AMERICANS

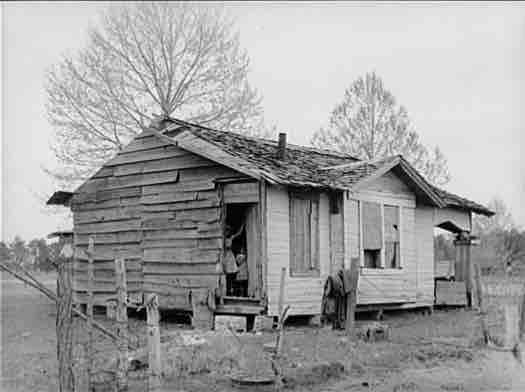

The Great Depression only worsened the already abysmal situation of African Americans. At the time when many white Americans struggled for survival, the struggle of black Americans only intensified. Segregation was rampant, racial violence common (particularly in the South), and all the economic ills that affected white communities hit black communities with an even more devastating force. While the overall unemployment reached approximately a quarter of the labor force, for black workers, the rate was well over 50%. Those who were able to find employment were excluded from better paying and more stable professions and usually held menial jobs, for which they were paid lower wages than their white fellow workers. The crisis in agriculture that began long before the onset of the Great Depression also greatly affected African Americans, many of whom still lived off the land, more often as sharecroppers and other tenants than landowners.

The legacy of the Roosevelt administration in respect to black Americans remains ambiguous at best. As the 1932 presidential candidate, Franklin Delano Roosevelt embraced the segregationist stand of the Democratic Party. Already as the president, he made many critical decisions driven by the need to please white Southerners, who held substantial power in Congress. He repeatedly refused to support anti-lynching legislation and ignored the black civil rights struggle. Neither Roosevelt nor the New Deal agenda attempted to battle segregation, particularly in the South. Simultaneously, no other president before appointed as many black officials to his administration. Many of them belonged to would be known as the Black Cabinet - a group of black experts and professionals who, analogically to Roosevelt's white advisers who formed his Brain Trust, gathered to advise the president on matters relevant to black communities. The Black Cabinet as a body segregated from their white counterparts demonstrates a tragic ambiguity in Roosevelt's approach to African Americans: he did make some effort to improve their situation but the effort was hardly radical and always curbed by racism existing in the American society.

Some of the First New Deal flagship programs either excluded or even hurt African Americans. For example, the 1933 Agricultural Adjustment Act (AAA) drove many black farmers from the land. As subsidies were paid to (usually white) landlords for not growing certain crops on a part of their land, black (and white) sharecroppers and other tenants were the first victims of the new policy. The 1933 National Recovery Administration, the main First New Deal agency responsible for industrial recovery, had hardly anything to offer to African Americans as National Industrial Recovery Act's (NIRA) provisions covered the industries, from which black workers were usually excluded. Neither farm nor domestic labor, two sectors where African Americans constituted substantial labor force, were covered under NIRA. Where black workers qualified for NIRA's provisions, white employers would often apply strategies that would still exclude them (e.g., changing the name of the position). Similarly, the original version (later amended) of the 1935 Social Security Act did not provide old-age pensions for farm and domestic workers. This stipulation affected many Americans but no other group more than African Americans and particularly African American women. Out of the latter group, the overwhelming majority of those who met the age requirement (65 or older), did not qualify for the pension because of their earlier employment in agriculture or domestic service. Analogously, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, which established federal minimum wage and maximum working hours, excluded agricultural and domestic labor.

However, other New Deal programs produced much more positive outcomes for African Americans. The New Deal agenda stipulated that up to 10% of all the programs' beneficiaries must be African Americans (approximately equal to the rate of black population in the U.S.). Black workers participated in all the major programs that created employment, including the Federal Emergency Relief Administration, the Civilian Conservation Corps, the Public Works Administration, and the Works Progress Administration. Under the provisions of the latter, the youth coming from the families that had at least one member working for WPA also received support that allowed them to continue high school or college education (program known as the National Youth Administration). Around 10% of the youth program beneficiaries were black.

In 1937, the Roosevelt administration finally addressed some challenges faced by black farmers. The Bankhead–Jones Farm Tenant Act of 1937 provided affordable loans to tenant farmers in order to purchase land but relatively few African Americans benefited from the Act's provisions. The Farm Security Administration, the major New Deal agency established to combat rural poverty, reached out to a much more substantial number of black farmers, tens of thousands of whom received agricultural loans.

Despite Roosevelt's refusal to support the black civil rights struggle and the mixed results that the New Deal programs produced for black Americans, many black voters changed their political loyalty and shifted towards Democrats. Although in 1932, African Americans supported Hoover, by the 1936 election they overwhelmingly voted in support of Roosevelt. Modest yet tangible changes that the New Deal promised to black Americans as well as a generational shift shaped this historical departure from the Republican Party. Historians also note that although Roosevelt embraced the existing racial divisions, he also surrounded himself with white government officials who endorsed interracial civil rights initiatives (e.g., Harold Ickes, Secretary of the Interior who battled segregation in the areas under his control, was earlier the president of the Chicago NAACP). While their impact was not huge, it was enough to push for some important changes, including a significantly higher number of African Americans in government jobs. Furthermore, Eleanor Roosevelt continued to push her husband to pay more attention to black leaders and needs of African Americans.

WOMEN AND THE NEW DEAL

Most New Deal programs did not aim to support women and operated under the assumption that women would be benefited implicitly, mostly as wives, mothers, and daughters of the men who were target beneficiaries. Men were seen as breadwinners and women as "dependents" and the New Deal agenda embraced the belief without any reservations. Moreover, common social norms pushed many women out of the labor market, usually after they got married or started having children. This, however, was a typical scenario for most white married women in cities. As black families were rarely given the economic opportunity that would allow only one member of the family to work, a much larger percentage of black women belonged to the active labor force. Similarly, women in rural areas, both black and white, could rarely afford not to work on the land that their families owned or leased. Finally, in the 1930s, an estimated 10% of American households were headed by women.

Nationally, two sectors relied heavily on female labor force: agriculture and domestic service. The same two sectors were also consistently excluded from the protective and reform labor legislation of the New Deal. The 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act, the 1935 National Labor Relations Act, and the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act all excluded agricultural and domestic workers. Even the 1935 Social Security Act (SSA) heavily discriminated against women. Under its provisions, not only were domestic and agricultural workers but also charity and religious organizations employees excluded from the old-age pension benefits. The latter were mostly women, both black and white. Furthermore, although SSA provided benefits for children in families without father present under the program known as the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC), many poor single mothers were excluded from its provisions. ADC did not support black mothers and many white mothers faced the moral judgement of their middle and upper class compatriots who decided that while some women deserved the support (e.g., widows or women abandoned by their husbands), other did not (e.g., unwed mothers).

Although most of the New Deal employment programs offered jobs to some women, they all consistently discriminated against female labor force. For example, the 1935 Works Progress Administration (WPA) employed mostly the women who could not rely on the support of male family members (household heads). As most employment programs, including WPA, stipulated that only one family member could benefit from public employment, the jobs would usually go to males (interestingly, the Civilian Conservation Corps that created jobs for young men only was not limited by this rule). Men were also seen as a more natural fit for WPA jobs since most of them were conventionally associated with male labor force (most notably, in the construction sector). Those available to women were analogously seen as an obvious fit for women, e.g., sewing or food production. Other common stereotypical female jobs, like teaching or administrative support, were aimed at more educated middle class women and thus remained beyond the reach of the poor working class women. The same was true for the New Deal programs that focused on arts (e.g., Federal Project Number One).

African-American sharecropper's cabin

In Marshall, Texas, 1939