The Age of Enlightenment

The American Enlightenment is used to describe a period of prolific intellectual writing and discussion during the mid- to late-18th century, 1715–1789, mirroring similar circumstances in Europe. Influenced by the scientific revolution of the 17th century, key Enlightenment thinkers applied scientific reasoning to studies of human nature, society, and religion. The intellectual leaders of the Enlightenment employed scientific experimentation and reasoning to discover general principles that governed the movement of planets, gravity, and natural law; acquire knowledge about philosophical principles; and challenge unquestioned authorities or principles. Fundamentally, the Enlightenment was a highly intellectual endeavor—drawing together the intellectual elites of Europe and the Americas to form a transatlantic academic coterie with one common language and shared worldview.

Political Influence

Politically, the age is distinguished by an emphasis on liberty, democracy, republicanism, and religious tolerance—culminating in the writings of Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson and the drafting of the United States Declaration of Independence. Attempts to reconcile science and religion led to the growing appeal of Deism, often resulting from a rejection of prophecy, miracle, and revealed religion. Historians have considered how the ideas of John Locke and republican ideas merged together to form republicanism in the United States.

Thomas Jefferson

Founding father and third president of the United States.

Religion

Enlightenment thinkers reacted against the authoritarianism, irrationality, and perceived obscurantism of the established churches. Philosophers such as Voltaire depicted organized Christianity as a tool of tyrants and oppressors and as being used to defend monarchism. It was seen as hostile to the development of reason and the progress of science, and it was incapable of verification.

For these philosophers, an acceptable alternative was Deism, the philosophical belief in a deity based on reason rather than on religious revelation or dogma. It was a popular perception among the philosophers, who adopted deistic attitudes to varying degrees. Deism greatly influenced intellectuals and several noteworthy 18th-century Americans such as John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Paine, and Thomas Jefferson. The most articulate exponent was Thomas Paine, whose The Age of Reason was written in France in the early 1790s and reached America soon thereafter. Drawing on the principles of Deism and the Enlightenment's aversion to established faiths, James Madison later enshrined religious tolerance as a fundamental American right in the United States Bill of Rights.

Liberalism and Republicanism: Key Thinkers

In the decades before the American Revolution in 1776, the intellectual and political leaders of the colonies studied history intently, looking for guides or models for good—and bad—government. They especially followed the development of republican ideas in England. For example, the English political theorist John Locke was a significant source of influence and inspiration to the American intellectual elite. Locke's Two Treatises of Government (1691) challenged the principle that hierarchical, monarchical systems of government originated from God's divine law. Locke argued that governments were created through a social contract with the people, and a ruler who broke this contract could be legitimately deposed through violent or peaceful means. Essentially, Locke claimed that since men created governments, they could also alter or abolish them.

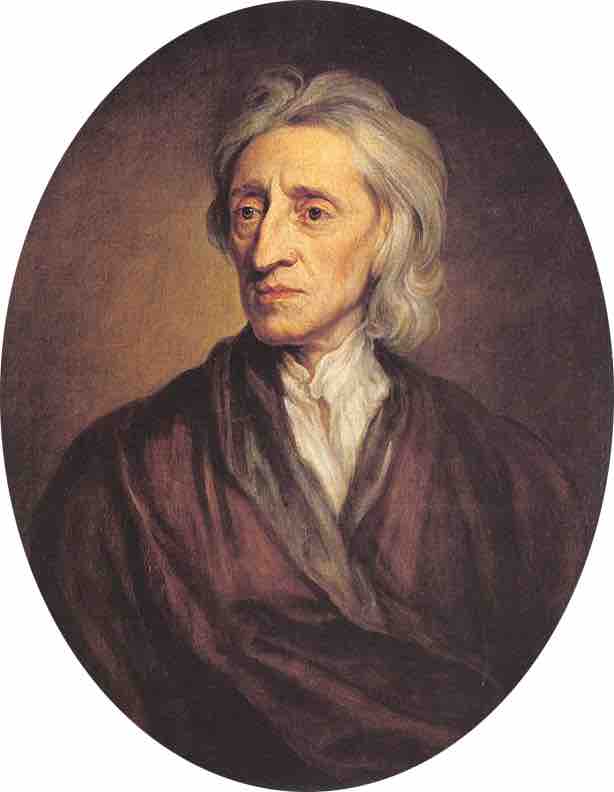

John Locke

John Locke is often credited with the creation of liberalism as a philosophical tradition.

Thomas Paine's Common Sense, published at the outset of the American Revolution, drew heavily on the theories of Locke and is largely considered one of the most virulent attacks on political despotism. Employing common language rather than the more academic prose employed by other Enlightenment writers, Paine argued that the North American colonies had a sacred duty to violently overthrow corrupt, monarchical British rule. Common Sense called for independence and challenged the largely accepted notion that a good government employed a balance of monarchy, aristocracy, and democracy. Instead, Paine called for a republican system of government, with no king or aristocracy.

Thomas Paine

Portrait of Thomas Paine by Auguste Millière.

The culmination of these enlightenment ideas occurred with Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence, in which he declared:

...to secure these rights [life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness] governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed; that whenever any form of government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the right of the people to alter or abolish it, and to institute a new government.

Drawing on Locke, Smith, and Paine, the Declaration of Independence thus asserted to Britain and other contemporary observers that both George III and Parliament were violating colonial rights and freedoms and the American colonies intended to sever ties with Britain. Essentially, the Declaration of Independence, heavily inspired by Enlightenment political theory, proclaimed that the American people were fighting to maintain their essential freedoms and liberties by overthrowing despotic, irrational tyranny.