Political Culture: Participation in Colonial Government

American colonial governments were a local enterprise rooted deeply in communities. For instance, elected bodies, specifically the assemblies and county governments, directly determined the development of a wide range of public and private business. These assemblies handled land grants, commercial subsidies, and taxation. They were also involved in the oversight of roads, taverns, schools, and relief of the poor, making them fundamental to the development of public and private enterprises in a particular region.

Participation in local courts was very high in the colonies. When the county court was in session, Anglo-American men traveled for miles to serve as witnesses and jurors. Americans sued each other at a very high rate, with binding decisions made by local judges and juries instead of a great lord (as in Britain). This promoted the rapid expansion of the legal profession, so that the intense involvement of lawyers in politics became characteristic of the American political system by the 1770s.

Role of Local Community Government

Widespread participation in local community governments was also distinctive of the American colonies. Unlike Europe, where aristocratic families and established churches dominated the political sphere, American political culture was relatively open to economic, social, religious, ethnic, and geographical interests (although still excluding the participation of American Indians, women, and African Americans). Merchants, landlords, petty farmers, artisans, Anglicans, Presbyterians, Quakers, Germans, Scotch Irish, Yankees, Yorkers, and many other groups participated in local community government life.

Competing Factions

None of the colonies had stable political parties of the sort that formed in the 1790s, although each had shifting factions that vied for power. This was especially true in the perennial battles between appointed governors and the elected assembly. For instance, there were often "country" and "court" factions representing those opposed to and in favor of, respectively, the governor's actions and agenda. British-appointed governors also faced various degrees of opposition and resistance over new colonial policies which resulted in much negotiation between assemblies, voting populations, and colonial authorities.

Massachusetts also had a strong populist faction that typically represented the province's lower classes. This was a possible effect of the state's 1691 charter, which had particularly low requirements for voting eligibility and strong rural representation in its assembly. Additionally, non-English ethnic groups had clusters of settlements, such as the Scotch Irish and the Germans. Although each group assimilated into the dominant English Protestant commercial and political culture, they tended to vote in blocs and politicians often negotiated with group leaders for support.

Conclusion

Hence, the colonial American political system was remarkably different from Europe, where widespread public participation in the political sphere by free white males was expected and enjoyed. Local leaders found themselves directly negotiating and engaging with a wider body politic that included elites as well as petty farmers and ethnic immigrants who had a voice in the political process. Local politics was entwined with local commercial development and with land grants, subsidies, and entrepreneurial incentives stemming from government grants and incentives. While politics in colonial America were public and relatively accessible to most social groups of white males, it was primarily localized in scope—the 13 colonies were not united by a confederate system across regional boundaries until the outset of the American Revolution.

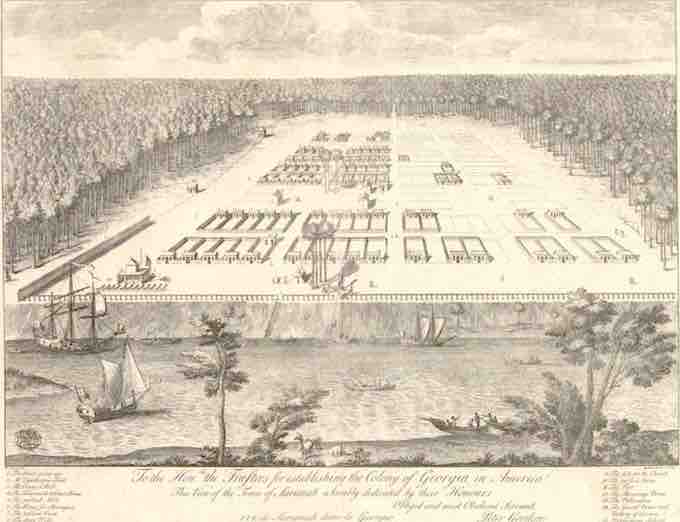

Savannah, Georgia

Widespread participation in both colonial and local community governments was widespread among free white males in the 18th century.