Women played a vital support role during the Civil War by supplying casualty care and nursing to Union and Confederate troops at field hospitals, raising funds for the war, and providing cooking and laundering services for soldiers. The absence of husbands, fathers, sons, and brothers meant that domestic manufacturing and farm labor also fell to women. A smaller proportion of women served as spies and soldiers or worked to free slaves.

Important Women of the Civil War

Harriet Tubman was a noted humanitarian, abolitionist, and spy. She is widely remembered for her work with the Underground Railroad, which she used to lead escaped slaves to the North for several years. She also worked for the Union Army when the Civil War began. Initially she worked as a cook, and then as a nurse in Port Royal. In June 1863, Tubman became the first woman to plan and execute an armed expedition in U.S. history, leading 300 soldiers 25 miles into the interior of South Carolina to free approximately 800 slaves. She continued her service a few months past the end of the war, attending to freed slaves and going on scouting expeditions for the army.

Harriet Tubman

Tubman was the first woman to lead an armed assault during the Civil War.

Dorothea Dix and Clara Barton are among the most prominent nurses of the Civil War. Dix served as the Union's Superintendent of Female Nurses throughout the war, overseeing more than 3,000 nurses. Though she met some resistance from individuals who did not want female nurses in their hospitals, Dix set many hiring guidelines and took over operational responsibilities that made her a prominent figure within the medical community. Barton, convinced by her father that it was her duty as a Christian to assist in the war effort, gained permission from Quartermaster Daniel Rucker to serve on the front lines, distributing stores, cleaning field hospitals, applying dressings, and serving food to wounded and ill soldiers. She served in close proximity to several large-scale and well-known battles, such as Antietam, Fredericksburg, and Second Bull Run. In 1864, Union General Benjamin Butler appointed her the “lady in charge” of the hospitals along the front of the Army of the James. During her service, she earned the nickname “Angel of the Battlefield,” and eventually achieved widespread recognition by lecturing about her war experiences.

United States Sanitary Commission

Many Northern women participated in the war effort by joining the United States Sanitary Commission (USSC), a private relief agency that lent support to sick and wounded soldiers of the U.S. Army, created in June 1861. Directed by Frederick Law Olmsted, this organization enlisted thousands of volunteers across the North. Volunteers worked as nurses; ran kitchens in army camps; administered hospital ships; ran soldiers' homes, lodges, and rests for traveling or disabled soldiers; made uniforms; and raised funds for the Union Army. The USSC also worked with Union veterans after the war to secure their bounties, back pay, and apply for pensions.

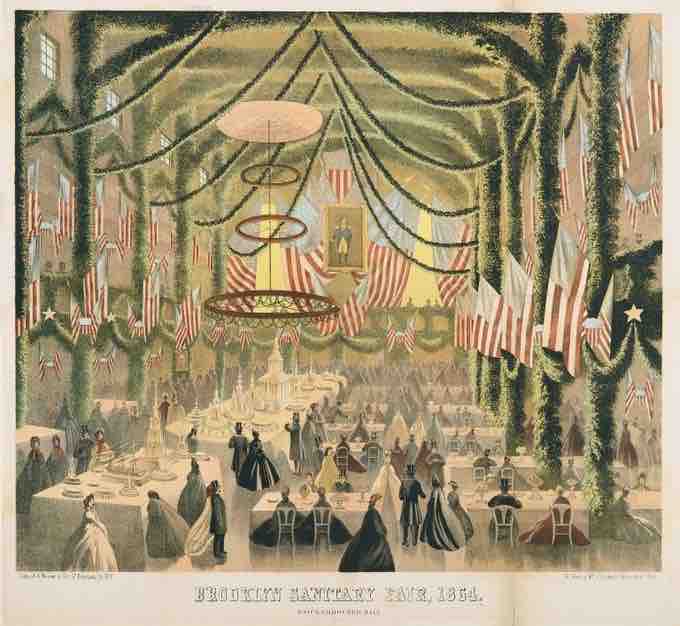

"Sanitary Fairs" were extremely successful fundraisers organized by the USSC that provided opportunities for local communities to participate in the national war effort. Fairs involved elaborate parades and large-scale exhibitions, including displays of art, mechanical technology, and period rooms. Over the course of the war, the USSC contributed more than$25 million to the Union.

"Brooklyn Sanitary Fair, 1864."

"Sanitary Fairs" were elaborate fundraisers for Union forces organized by the USSC.

Women Spies

Pauline Cushman, an actress, served as a Union spy after being approached by two pro-Confederate men after a performance, asking her to toast Confederate President Jefferson Davis. She agreed, causing her to lose her job in the theater, but she used the opportunity to ingratiate herself to the rebels while approaching the Union to offer her services as a spy. During her service, she was able to conceal battle plans and drawings in her shoes to pass along to Union officials; however, she was caught and tried by a Confederate military court, which found her guilty and sentenced her to death. She managed to avoid execution by playing up a preexisting illness, causing the Confederates to postpone her hanging. In the meantime, Union forces invaded the area, and she was saved from her fate by a matter of three days. She was awarded the rank of "Brevet Major" by General James Garfield and was commended by President Lincoln for her service to the Union.

Rose O’Neal Greenhow and Belle Boyd both worked as Confederate spies. Greenhow, a socialite in Washington, D.C., when the war broke out, was able to leverage her position in political circles and friendships with important civic leaders to pass along key military information to the Confederates at the beginning of the war. She has been credited with ensuring the South’s victory at the First Battle of Bull Run in late July 1861, for example. Greenhow was discovered and captured by Union forces in August of 1861. She was tried for espionage the following year and imprisoned for almost five months, but subsequently was deported to the Confederate states where she resumed service to the Confederacy. She sailed to Europe on a diplomatic mission to France and Britain from 1863 to 1864, during which time she wrote and published a memoir that was popularly received in Britain. Upon return to the Confederacy in 1864, her ship ran aground off Wilmington, North Carolina, and she drowned while attempting escape from a Union gunboat. The Confederacy honored her with a military funeral.

Belle Boyd was also a Confederate spy. Her career began by chance—a supporter of the Confederacy, she was under close supervision by Union forces following reports that she had raised Confederate flags in her room. She earned the monikers “Cleopatra of the Secession” and “Siren of the Shenandoah,” charming the soldiers sent to question her and ingratiating herself to them. She would learn secrets from at least one of them that she then passed along to Confederate officers via her slave, Eliza Hopewell. Over time she became more bold, hiding herself in a closet room of a hotel lobby where Union staff were gathering and eavesdropping on their orders. She passed that information along to General Stonewall Jackson, who expressed great gratitude to her, but she was later found out. Boyd was arrested on July 29, 1862, and imprisoned at the Old Capitol Prison in Washington, D.C., for a little over a month.