In the period of uncertainty leading up to the formal declaration of war, the Second Continental Congress attempted to pacify the British and declare allegiance to the Crown, while simultaneously asserting independence and engaging British forces in armed conflict. When the Second Continental Congress convened in May 1775, most delegates supported John Dickinson in his efforts to reconcile with George III of Great Britain. However, a small faction of delegates, led by John Adams, argued that war was inevitable.

The Olive Branch Petition was adopted by the Continental Congress in July 1775, in an attempt to avoid a war with Great Britain. The petition vowed allegiance to the Crown and entreated the king to prevent further conflict, claiming that the colonies did not seek independence but merely wanted to negotiate trade and tax regulations with Great Britain. The petition asked for free trade and taxes equal to those levied on the people in Great Britain, or alternatively, no taxes and strict trade regulations. The letter was sent to London on July 8, 1775. The petition was rejected, and in August 1775, A Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition (or the Proclamation of Rebellion) formally declared that the colonies were in rebellion.

The Proclamation of Rebellion was written before the Olive Branch Petition reached the British. When the petition arrived, it was rejected unseen by King George III, and the Second Continental Congress was dismissed as an illegal assembly of rebels. At the same time, the British also confiscated a letter authored by John Adams, which expressed frustration with attempts to make peace with the British. This letter was used as a propaganda tool to demonstrate the insincerity of the Olive Branch Petition.

The king's rejection gave Adams and others who favored revolution the opportunity they needed to push for independence. The rejection of the "olive branch" polarized the issue in the minds of many colonists who realized that from that point forward, the choice was between full independence or full submission to British rule.

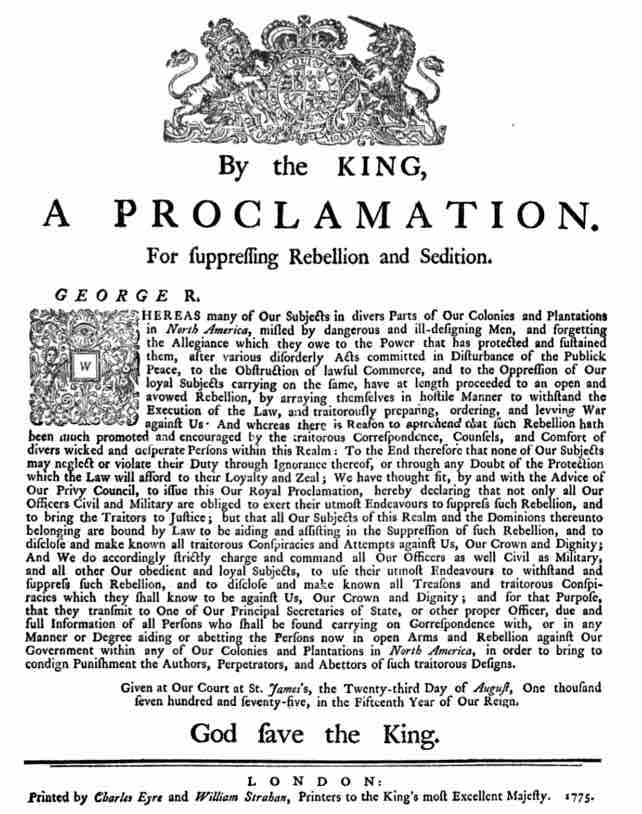

In August 1775, upon learning of the Battle of Bunker Hill, King George III issued a Proclamation for Suppressing Rebellion and Sedition. This document declared the North American colonies to be in a state of rebellion and ordered British officers and loyal subjects to suppress this uprising. On October 26, 1775, King George III expanded on the Proclamation of Rebellion in his Speech from the Throne at the opening of Parliament. The king insisted that rebellion was being fomented by a "desperate conspiracy" of leaders whose claims of allegiance to him were not genuine. King George indicated that he intended to deal with the crisis with armed force.

Proclamation of Rebellion, 1775

The Proclamation of Rebellion was King George III's response to the Olive Branch Petition.

The Second Continental Congress issued a response to the Proclamation of Rebellion on December 6, 1775, saying that despite their unwavering loyalty to the Crown, the British Parliament did not have a legitimate claim to authority over the colonies while they did not have democratic representation. The Second Continental Congress maintained that they still hoped to avoid a "civil war."

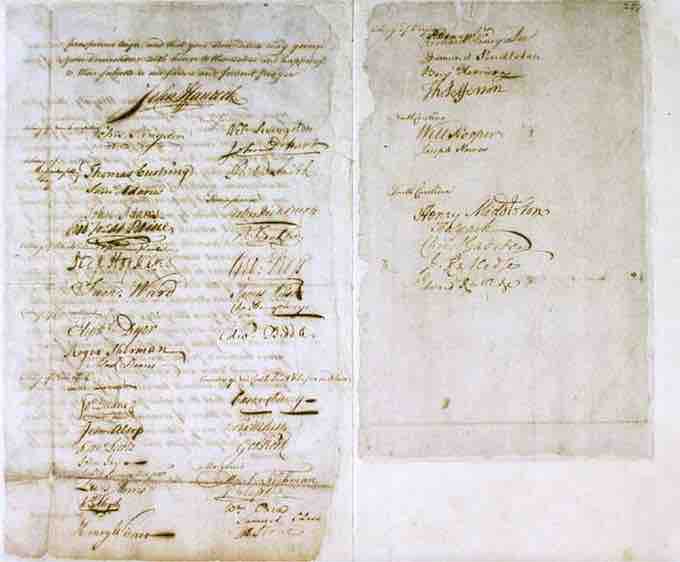

Olive Branch Petition, 1775

The Olive Branch Petition, issued by the Second Congress, was a final attempt at reconciliation with the British.