The Philadelphia campaign (1777-1778) was a successful British initiative to gain control of Philadelphia, the seat of the Second Continental Congress. Following his unsuccessful attempt to draw Continental Army General George Washington into a battle in northern New Jersey, British General William Howe instead turned his attention towards Philadelphia.

William Howe, 1777

Despite his victories in New York and Philadelphia, Howe resigned in October 1777, in response to his role in the British defeat at Saratoga.

In 1777, General Howe began mobilizing his forces for an assault on the city-state. In late August, he landed 15,000 troops at the northern end of Chesapeake Bay, 50 miles southwest of Philadelphia. General Washington positioned 11,000 men between Howe and Philadelphia, but was outflanked and driven back at the Battle of Brandywine on September 11, 1777. The Continental Army suffered over 1,000 casualties in this exchange; the British lost 500. The Continental Congress abandoned Philadelphia, relocating to York, Pennsylvania. British and Revolutionary forces skirmished west of Philadelphia for several days, but on September 26, Howe marched into Philadelphia unopposed.

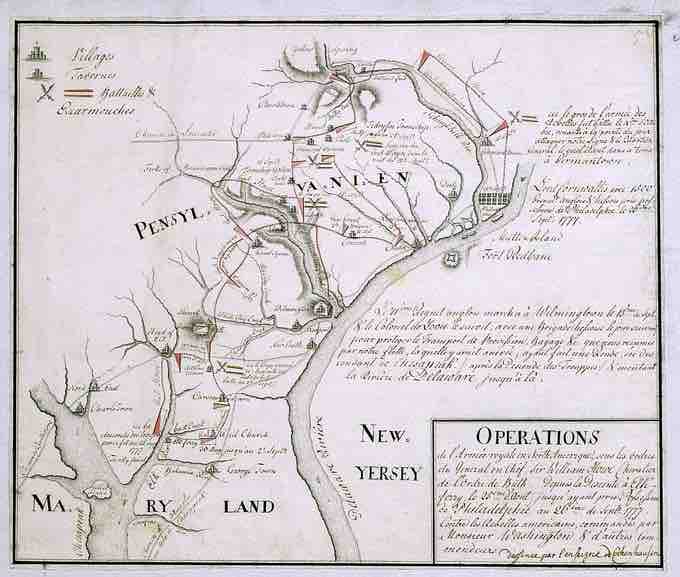

Hessian Map of the Philadelphia Campaign

General Howe was supported by Hessian troops as he took Philadelphia.

Though Howe successfully captured the Patriot capital, he neglected the concurrent campaign of General John Burgoyne further north. Burgoyne believed that isolating New York and New England from the rest of the colonies would result in a decisive victory for the British and possibly even an end to the war. In June 1777, Burgoyne marched south from Quebec toward Albany with 8,000 troops severely weakened by Patriot efforts to cut off British supply lines via raids and scorched earth tactics. By September 19th, Burgoyne won a small tactical victory against Continental General Horatio Gates at the Battle of Freeman’s Farm, the First Battle of Saratoga. The cost to the British forces was monumental with a total of 600 casualties, or 10 percent of troops. Desertions began to further reduce the size of the British army and critical supplies, including food, were constantly in short supplies. Skirmishing continued after the battle for days while Burgoyne waited for reinforcements from New York City.

Meanwhile, a steady stream of Patriot militias swelled the ranks of the Continental Army to over 15,000 men. Burgoyne, who had put his army on short rations in early October, decided to launch a desperate reconnaissance mission and attack the left flank of the Continental Army with only 1,700 troops. The British were quickly defeated at the Battle of Bemis Heights, or the Second Battle of Saratoga, with nearly 900 casualties versus the mere 150 suffered by the Continental Army. Burgoyne surrendered his army to the Patriots on October 17, marking the end of British control of the North.

Howe's decision to capture Philadelphia in late September left Burgoyne without the crucial support he needed to defeat the Patriots. As such, Burgoyne's operation ended in disaster for the British at Saratoga and brought France into the war. General Howe resigned during the occupation of Philadelphia and was replaced by his second-in-command, General Sir Henry Clinton. In 1778, Clinton evacuated troops from Philadelphia to increase British defenses in New York City. Washington, however, managed to intercept the evacuating forces at the New Jersey Monmouth Court House, resulting in one of the largest and most infamous battles of the Revolutionary War.

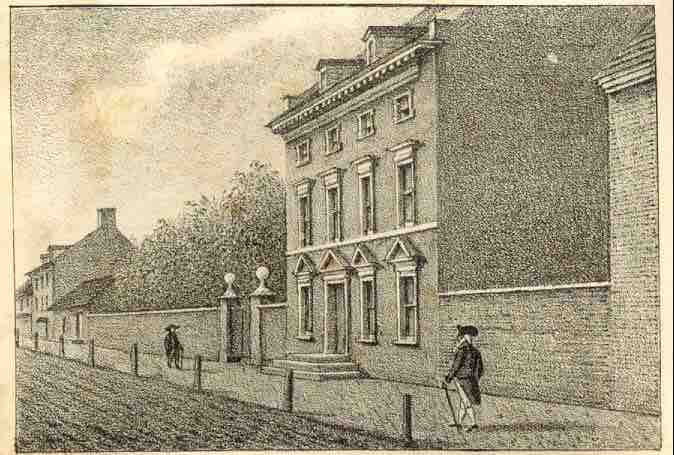

"Residence of Washington in High Street, Philadelphia" by William L. Breton, ca. 1828-30

Howe made this house his headquarters during the British occupation of Philadelphia.