The Embargo Act of 1807 was a general embargo enacted by the U.S. Congress prohibiting all foreign commerce. It was primarily directed toward Great Britain and France during the Napoleonic Wars.

Background

The embargo was imposed in response to flagrant violations of U.S. neutrality, in which American merchantmen and their cargoes were seized as contraband of war by the British and French Navies. The British Royal Navy, in particular, resorted to the practice of impressment, forcing thousands of American seamen into service on their warships. Both Great Britain and France, in the midst of a war for control of Europe, justified the plunder of U.S. shipping as incidental to war and necessary for their success. The official orders issued in support of these actions by European powers were widely recognized in the United States as grounds for a U.S. declaration of war.

"Peaceful Coercion"

As these attacks on U.S. merchant ships mounted, President Thomas Jefferson weighed public support for retaliation. He recommended that Congress respond with commercial warfare, rather than with military mobilization. Both Jefferson and Madison viewed war as particularly fatal to republican government, and Jefferson sought to avoid war in favor of what he called "peaceful coercion." By restricting trade in crucial raw materials, Jefferson hoped to bring the British and French economies and their respective war machines to a halt, after which (he assumed) the European powers would show greater respect for the rights of American shipping. To this end, Jefferson signed the Embargo Act into law on December 22, 1807, after passage by the Republican-dominated Congress.

Implications

The embargo, which lasted from December 1807 to March 1809, turned out to be impractical as a coercive measure and was a failure both diplomatically and economically. The legislation inflicted devastating burdens on the U.S. economy and the American people, effectively throttling American overseas trade. All areas of the United States suffered: In commercial New England and the Middle Atlantic states, ships rotted at the wharves, and in the agricultural areas, particularly in the South, farmers and planters could not sell their crops on the international market. For New England, and especially for the Middle Atlantic states, there was some consolation, for the scarcity of European goods stimulated the development of American industry.

At the same time, the British were still able to export goods to America: Initial loopholes overlooked coastal vessels from Canada smuggling goods, whaling ships, and privateers from overseas. Widespread disregard of the law meant enforcement was difficult, and the embargo became a financial disaster for the United States.

The embargo also undermined national unity in the United States, provoking bitter protests, especially in New England commercial centers. The issue vastly increased support for the Federalist Party and led to huge gains in its representation in Congress and in the electoral college in 1808. Thomas Jefferson's doctrinaire approach to enforcing the embargo violated a key Democratic-Republican precept: commitment to limited government. Many Democratic-Republicans felt that Jefferson's authorization of heavy-handed enforcement by federal authorities violated both sectional interests and individual liberties.

Despite its unpopular nature, the Embargo Act did have some limited, unintended benefits. For example, fledgling capitalist workers responded by bringing in fresh capital and labor to New England textile and other manufacturing industries, decreasing American reliance on British imports.

After 15 months, the embargo was revoked on March 1, 1809, in the final days of Jefferson's presidency. It was replaced by the Non-Intercourse Act of 1809, which lifted all embargoes on American shipping except for those bound for British or French ports. The intent was to damage the economies of the United Kingdom and France. Like its predecessor, the Non-Intercourse Act was mostly ineffective and contributed to the outbreak of the War of 1812.

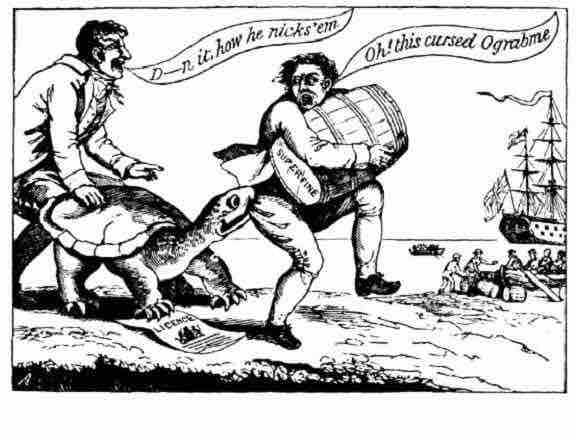

1807 embargo cartoon

This 1807 political cartoon satirizes the Embargo Act. Here, a turtle named "Ograbme" ("Embargo" spelled backward) bites a merchant/smuggler.