Background

President Jefferson had long been interested in the trans-Mississippi West. Despite three centuries of European emigration, North America beyond the Mississippi River had remained largely untouched. Only a few French-Canadian trappers had ventured that far west. Jefferson was highly interested in surveying the flora, fauna, geology, and ethnography of the vast territory west of the Mississippi River. Thus, in 1804, he commissioned his personal secretary, Meriwether Lewis, to join frontiersman and soldier Captain William Clark in recruiting a "Corps of Discovery." Their mission, in addition to surveying and recording the geography and observing the native peoples of the region, was to find a passage to the Pacific Ocean in order to facilitate trade with Asia.

Jefferson wanted to improve the ability of American merchants to access the ports of China. Establishing a river route from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean was crucial to capturing a portion of the fur trade that had proven so profitable to Great Britain. He also wanted to legitimize American land claims to rivals such as Great Britain and Spain. Establishing an overland route to the Pacific also would bolster U.S. claims to the Pacific Northwest. Lewis and Clark were thus instructed to map the territory through which they would pass and to explore all tributaries of the Missouri River.

The Expedition

Having gathered woodsmen from across the country for the expedition, Lewis and Clark set out from St. Louis in the summer of 1804, rowing and sailing in long-boats up the Missouri River. Here, the easterners, accustomed to a forested landscape, were amazed to discover the vastness of the great prairies and plains of central North America.

The corps wintered among the Mandan Indians at the falls of the Missouri, in what is today North Dakota, where they met a French fur trapper named Toussaint Charbonneau. When the corps left in the spring of 1805, Charbonneau accompanied them as a guide and interpreter, bringing along his teenage Shoshone wife, Sacagawea, and their newborn son. Charbonneau knew the land better than the Americans, and Sacagawea proved invaluable as an interpreter and a guide; in addition, the presence of a young woman and her infant convinced many groups that the men were not a war party and meant no harm.

Relations with American Indians

The corps set about making friends with American Indian tribes while simultaneously attempting to assert American power over the territory. In an effort to assert control, Lewis would let out a blast of his air rifle, a relatively new piece of technology the American Indians had never seen. The corps followed native custom by distributing gifts—including shirts, ribbons, and kettles—as a sign of goodwill. The explorers presented American Indian leaders with medallions, many of which bore Jefferson’s image, and invited them to visit their new “ruler” in the East. These medallions, or peace medals, were meant to allow future explorers to identify friendly American Indian tribes.

Not all efforts to assert U.S. dominance were peaceful, however, and several American Indian tribes rejected the expedition's intrusion onto their land. An encounter with the Blackfoot turned hostile, for example, and members of the corps killed two Blackfoot men.

Reaching the Pacific

After spending eighteen long months on the trail and nearly starving to death in the Bitterroot Mountains of Montana, the Corps of Discovery finally reached the Pacific Ocean in 1805 and spent the winter of 1805–1806 in Oregon. They returned to St. Louis later in 1806 having lost only one man, who had died of appendicitis. Upon their return, Meriwether Lewis was named governor of the Louisiana Territory. He died only three years later under circumstances that are still disputed, before he could write a complete account of what the expedition had discovered.

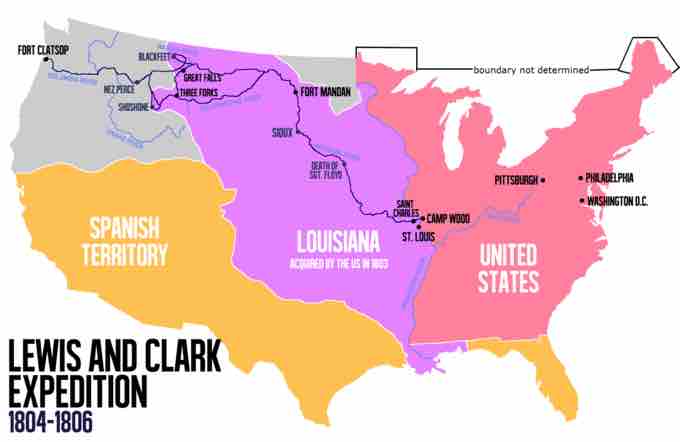

Lewis and Clark Expedition

This map illustrates the route of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, through the Louisiana Territory and across the present-day Pacific Northwest to the Pacific Ocean.

Effects of the Expedition

The Corps of Discovery accomplished many of the goals Jefferson had set. The men traveled across the North American continent and established relationships with many American Indian tribes, paving the way for fur traders and the establishment of trading posts, which later solidified U.S. claims to Oregon. Delegates of several American Indian tribes went to Washington to meet the president. The expedition collected hundreds of plant and animal specimens, several of which were named for Lewis and Clark in recognition of their efforts.

The information the expedition brought back proved invaluable, not only from a scientific standpoint, but also for purposes of colonization. With the territory now more accurately mapped, the United States felt more internal justification for its illegal claim over the western lands of the American Indians.