Religion and religious institutions had a massive impact on the Civil Rights Movement. On the one hand, major denominations supported the movement financially and intellectually and its many leaders were passionate ministers with great oratory skills that were critical to conveying the inspiring message of the civil rights struggle. On the other, black churches served as sites of organization, education, and community engagement for the hundreds of thousands of anonymous supporters of the movement. Historians also note that churches were places where many anonymous black women, so often excluded from the narratives of the Civil Rights Movement, organized and supported the civil rights struggle.

The SCLC

The Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) is an African-American civil rights organization that was central to the Civil Rights Movement. The group was created in 1957 to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct non-violent protests in the pursuit of civil rights reform. During its early years, SCLC struggled to gain footholds in black churches and communities across the South. Social activism faced fierce repression from police, the White Citizens' Council, and the Ku Klux Klan. Only a few churches defied the white-dominated status quo by affiliating with SCLC, and those that did risked economic retaliation, arson, and bombings.

SCLC's advocacy of boycotts and other forms of nonviolent protest was controversial. Traditionally, leadership in black communities came from the educated elite—ministers, professionals, teachers, etc.—who spoke for and on behalf of the laborers, maids, farm-hands, and working poor who made up the bulk of the black population. Many of these traditional leaders were uneasy at involving ordinary African Americans in mass activity such as boycotts and marches. SCLC's belief that churches should be involved in political activism against social ills was also deeply controversial. Many ministers and religious leaders—both black and white—thought that the role of the church was to focus on the spiritual needs of the congregation and perform charitable works to aid the needy. To some of them, the social-political activity of Dr. King (SCLC's first president) and SCLC amounted to dangerous radicalism which they strongly opposed.

BIRMINGHAM CAMPAIGN

The 1963 SCLC campaign was a movement to bring attention to the integration efforts of African Americans in Birmingham, Alabama. Led by Martin Luther King, Jr., James Bevel, Fred Shuttlesworth and others, the campaign of nonviolent direct action culminated in widely publicized confrontations between young black students and white civic authorities, and eventually led the municipal government to change the city's discrimination laws. Unlike the earlier efforts on Albany, which focused on the desegregation of the entire city, the campaign focused on more narrowly defined goals: the desegregation of Birmingham's downtown stores, fair hiring practices in shops and city employment, the reopening of public parks, and the creation of a bi-racial committee to oversee the desegregation of Birmingham's public schools. The brutal response of local police, led by Public Safety Commissioner "Bull" Connor, stood in stark contrast to the nonviolent civil disobedience of the activists. After weeks of various forms of nonviolent disobiedience, the campaign produced the desired results. In June 1963, the Jim Crow signs regulating segregated public places in Birmingham were taken down.

Three months later, on September 15, 1963, four members of the Ku Klux Klan planted at least 15 sticks of dynamite attached to a timing device beneath the front steps of the 16th Street Baptist Church. The church was one of the most important places of organization and protest during the campaign. The explosion at the church killed four girls and injured 22 others. Although the FBI had concluded in 1965 that the bombing had been committed by four known Ku Klux Klansmen and segregationists, no prosecutions ensued until 1977, with two men sentenced to life imprisonment as late as 2001 and 2002 respectively and one never being charged.

MARCH ON WASHINGTON

After the Birmingham Campaign, SCLC called for massive protests in Washington D.C., aiming for new civil rights legislation that would outlaw segregation nationwide. Although the march originated in earlier ideas and efforts of secular black leaders A. Philip Randolph and Bayard Rustin, the overall presence of religious values that shaped the Civil Rights Movement marked also the 1963 march. Its crowning moment was Dr. King's famous "I Have a Dream" speech in which he articulated the hopes and aspirations of the Civil Rights Movement rooted in two cherished gospels—the Old Testament and the unfulfilled promise of the American creed. It is estimated that between 200,000 and 300,000 participated in the march.

ST. AUGUSTINE PROTESTS

When civil rights activists protesting segregation in St. Augustine, Florida were met with arrests and Ku Klux Klan violence, the local SCLC affiliate appealed to Dr. King for assistance in the spring of 1964. SCLC sent staff to help organize and lead demonstrations and mobilized support for St. Augustine in the North. Hundreds were arrested during sit-ins and marches opposing segregation—so many that the jails were filled and the overflow prisoners had to be held in outdoor stockades.

Nightly marches to the Old Slave Market were attacked by white mobs, and when African Americans attempted to integrate "white-only" beaches they were assaulted by police who beat them with clubs. On June 11, Dr. King and other SCLC leaders were arrested for trying to lunch at the Monson Motel restaurant, and when an integrated group of young protesters tried to use the motel swimming pool, the owner poured acid into the water. King sent a "Letter from the St. Augustine Jail" to a northern supporter, Rabbi Israel Dresner of New Jersey, urging him to recruit others to participate in the movement. This resulted, a week later, in the largest mass arrest of rabbis in American history—while conducting a pray-in at the Monson. TV and newspaper stories about St. Augustine helped build public support for the Civil Rights Act of 1964 being debated in Congress.

SELMA VOTING RIGHTS CAMPAIGN AND MARCH TO MONTGOMERY

When voter registration and civil rights activity in Selma, Alabama was blocked by an illegal injunction, the Dallas County Voters League (DCVL) asked SCLC for assistance. Dr. King, SCLC, and DCVL chose Selma, Alabama as the site for a major campaign that would demand national voting rights legislation in the same way that the Birmingham and St. Augustine campaigns won passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Nonviolent mass marches demanded the right to vote, and the jails filled up with arrested protesters, many of them students. On February 1, Dr. King and Rev. Abernathy were arrested. Voter registration efforts and protest marches spread to the surrounding Black Belt counties—Perry, Wilcox, Marengo, Greene, and Hale.

On February 18, an Alabama State Trooper shot and killed Jimmie Lee Jackson during a voting rights protest in Marion, county seat of Perry County. In response, on March 7 close to 600 protesters attempted to march from Selma to Montgomery to present their grievances to Governor Wallace. Led by Reverend Hosea Williams of SCLC and John Lewis of SNCC, the marchers were attacked by state Ttoopers, deputy sheriffs, and mounted possemen who used tear gas, clubs, and bull whips to drive them back to Brown Chapel. Dr. King called on clergy and people of conscience to support the black citizens of Selma. Thousands of religious leaders and ordinary Americans came to demand voting rights for all.

After many more protests, arrests, and legal maneuvering, a Federal judge ordered Alabama to allow the march to Montgomery. It began on March 21 and arrived in Montgomery on the 24th. On the 25th, an estimated 25,000 protesters marched to the steps of the Alabama capitol where Dr. King spoke on the voting rights struggle. Within five months, Congress and President Lyndon Johnson responded to the enormous public pressure generated by the Voting Rights Campaign by enacting into law the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

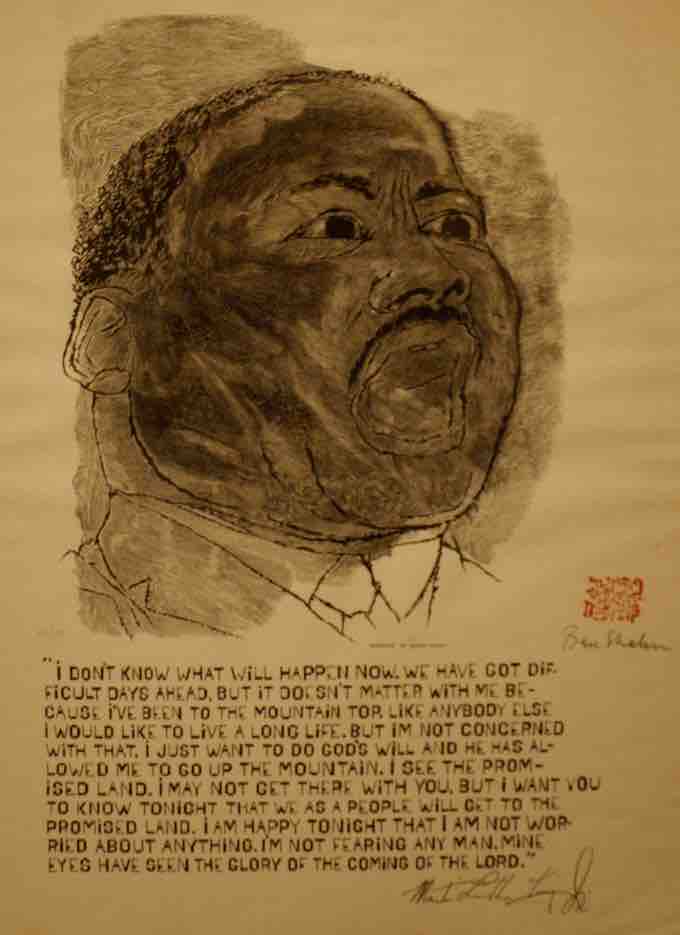

SCLC Fundraising Poster Depicting Martin Luther King, Jr.

Shortly after Martin Luther King's death, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference used this poster—issued in an edition of one hundred—for a fundraising drive. The portrait was based on a drawing by Ben Shahn, commissioned for Time magazine's March 19, 1965 cover. Time's publisher noted that Shahn, "as famed in his own medium of protest as King is in his," greatly admired the civil rights leader and felt that King had "moved more people by his oratory" than anyone else. After the artist's friend Stefan Martin made a wood engraving based on the drawing, Shahn authorized its use in support of various causes. This 1968 poster included two additions to the portrait: the orange seal or artist's "chop" that Shahn had made in Japan, incorporating the letters of the Hebrew alphabet and an excerpt from King's famous "mountaintop" speech in the artist's own distinctive lettering.

KU KLUX KLAN'S USE OF RELIGION

Similarly to the arguments used by earlier proponents of slavery, many segregationist used Christianity to justify racism and racial violence. Ku Klux Klan remains the most illustrative example of this trend. A religious tone was present in Klan's activities from the beginning. Historian Brian Farmer estimates that during the period of the Second Klan (1915-1944), two-thirds of the national Klan lecturers were Protestant ministers. Religion was a major selling point for the organization. Klansmen embraced Protestantism as an essential component of their white supremacist, anti-Catholic, and paternalistic formulation of American democracy and national culture. Their cross was a religious symbol, and their ritual honored Bibles and local ministers. The 1950s/60s Klan drew on those earlier symbols and ideologies.

Beginning in the 1950s, individual Klan groups in Birmingham, Alabama, began to resist social change and blacks' efforts to improve their lives by bombing houses in transitional neighborhoods. There were so many bombings in Birmingham of blacks' homes by Klan groups in the 1950s that the city's nickname was "Bombingham." During the tenure of Bull Connor as police commissioner in the city, Klan groups were closely allied with the police and operated with impunity. When the Freedom Riders arrived in Birmingham, Connor gave Klan members fifteen minutes to attack the riders before sending in the police to quell the attack. When local and state authorities failed to protect the Freedom Riders and activists, the federal government established effective intervention.

In states such as Alabama and Mississippi, Klan members forged alliances with governors' administrations. In Birmingham and elsewhere, the KKK groups bombed the houses of civil rights activists. In some cases they used physical violence, intimidation and assassination directly against individuals. Continuing disfranchisement of African Americans across the South meant that most could not serve on juries, which were all white.