Martin Luther King, Jr. (January 15, 1929 – April 4, 1968) was an American clergyman, activist, and prominent leader in the African-American Civil Rights Movement. He is best known for his practice of nonviolent civil disobedience based on his Christian beliefs. Later in his career, King's message highlighted more radical social justice questions, which alienated many of his liberal allies.

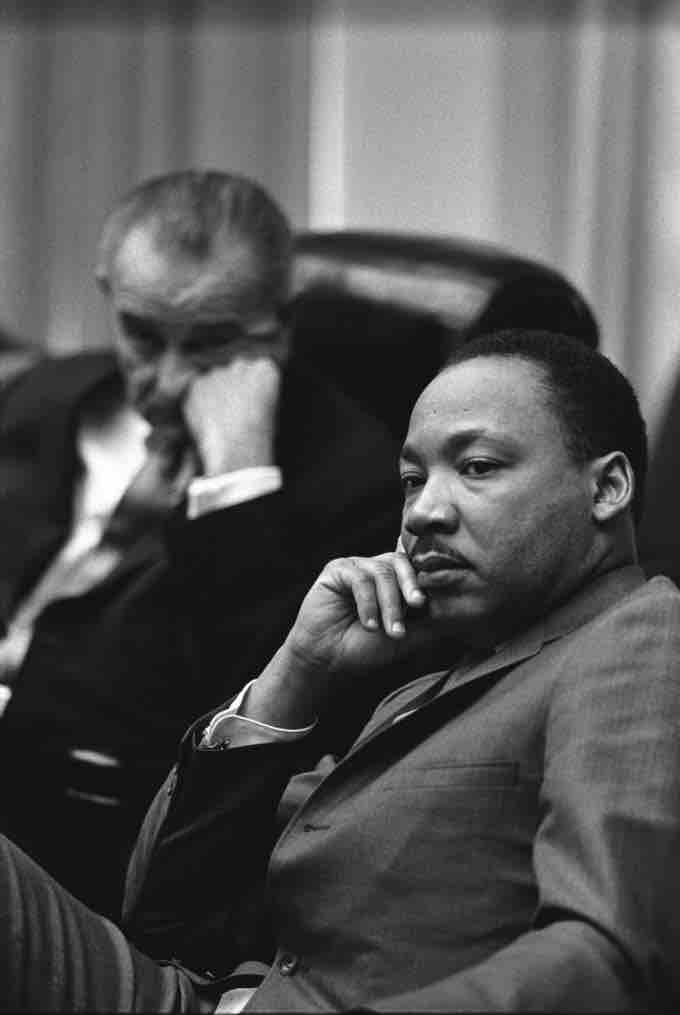

Martin Luther King, Jr and Lyndon Johnson

President Lyndon B. Johnson and Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. meet at the White House, 1966.

EARLY LIFE

King was born on January 15, 1929, in Atlanta, Georgia, to Reverend Martin Luther King Sr., and Alberta Williams King. Growing up in Atlanta, he attended Booker T. Washington High School. As a teenager, he was already known for his public speaking ability, joined the school's debate team, and became the youngest assistant manager of a newspaper delivery station for the Atlanta Journal at age 13. A precocious student, he skipped both the ninth and the twelfth grades of high school. It was during King's junior year that Morehouse College announced it would accept any high school juniors who could pass its entrance exam. At that time, most of the students had abandoned their studies to participate in World War II. Due to this, the school became desperate to fill in classrooms. At age 15, King passed the exam and entered Morehouse. The summer before his last year at Morehouse, in 1947, an eighteen-year-old King made the choice to enter the ministry.

In 1948, King graduated from Morehouse with a B.A. degree in sociology, and enrolled in Crozer Theological Seminary in Chester, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with a B.Div. degree in 1951. In 1953, he married Coretta Scott on the lawn of her parents' house in her hometown of Heiberger, Alabama. They became the parents of four children. During their marriage, King limited Coretta's role in the Civil Rights Movement, expecting her to be a housewife and mother. In 1954, he became pastor of the Dexter Avenue Baptist Church in Montgomery, Alabama, and a year later, received his Ph.D. degree in systematic theology at Boston University. However, an academic inquiry concluded in October 1991 that portions of his dissertation had been plagiarized and he had acted improperly.

NATIONAL PROMINENCE

King's first involvement in the Civil Rights Movement that attracted national attention was his leadership over the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott. In 1957, King, Ralph Abernathy, Fred Shuttlesworth, Joseph Lowery, and other civil rights activists founded the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The group was created to harness the moral authority and organizing power of black churches to conduct non-violent protests in the pursuit of civil rights reform. King led the SCLC until his death. In December 1961, King and the SCLC became involved in the Albany Movement - a desegregation coalition formed in Albany, Georgia. The movement mobilized thousands of citizens for a broad-front nonviolent attack on every aspect of segregation within the city and attracted nationwide attention.

After nearly a year of intense activism with few tangible results, the movement began to deteriorate. King requested a halt to all demonstrations and a "Day of Penance" to promote nonviolence and maintain the moral high ground. Divisions within the black community and the canny, low-key response by local government defeated efforts. Though the Albany effort proved a key lesson in tactics for Dr. King and the national civil rights movement, the national media was highly critical of King's role in the defeat, and the SCLC's lack of results contributed to a growing gulf between the organization and the more radical SNCC. After Albany, King sought to choose engagements for the SCLC in which he could control the circumstances, rather than entering into pre-existing situations.

In April 1963, the SCLC initiated a campaign against racial segregation and economic injustice in Birmingham, Alabama. The campaign used nonviolent but intentionally confrontational tactics, developed in part by Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker. Black Americans in Birmingham, organizing with the SCLC, occupied public spaces with marches and sit-ins, openly violating unjust laws. King was arrested and jailed early in the campaign—his 13th arrest out of 29. From his cell, he composed the now-famous "Letter from Birmingham Jail," which responded to calls for King to discontinue his nonviolent protests and instead rely on the court system to bring about social change.

King, representing the SCLC, was among the leaders of the so-called "Big Six" civil rights organizations that were instrumental in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, which took place on August 28, 1963. Originally, the march was conceived as a very public opportunity to dramatize the desperate condition of African Americans in the southern United States and present organizers' concerns and grievances directly to the seat of power in the nation's capital. At the time, it was the largest gathering of protesters in Washington, D.C.'s history. King's "I Have a Dream" speech electrified the crowd.

On October 14, 1964, King received the Nobel Peace Prize for combating racial inequality through nonviolence. In the following years leading up to his death, he expanded his focus to include poverty and the Vietnam War—alienating many of his liberal allies, particularly with a 1967 speech entitled "Beyond Vietnam." The speech reflected King's evolving political advocacy in his later years. He frequently spoke of the need for fundamental changes in the political and economic life of the nation, and expressed his opposition to the war and his desire to see a redistribution of resources to correct racial and economic injustice. He guarded his language in public to avoid being linked to communism by his enemies, but in private he sometimes spoke of his support for democratic socialism.

In 1968, King and the SCLC organized the "Poor People's Campaign" to address issues of economic justice. King traveled the country to assemble "a multiracial army of the poor" that would march on Washington to engage in nonviolent civil disobedience at the Capitol until Congress created an "economic bill of rights" for poor Americans. King and the SCLC called on the government to invest in rebuilding America's cities. The Poor People's Campaign was controversial even within the Civil Rights Movement.

ASSASSINATION AND LEGACY

On March 29, 1968, King went to Memphis, Tennessee in support of the black sanitary public works employees, which had been on strike for 17 days in an effort to attain higher wages and ensure fairer treatment. While standing on the second floor balcony of a motel, King was shot by escaped convict James Earl Ray. One hour later, King was pronounced dead at St Joseph's hospital.

King's main legacy was to secure progress on civil rights in the U.S. Just days after King's assassination, Congress passed the Civil Rights Act of 1968. Title VIII of the Act, commonly known as the Fair Housing Act, prohibited discrimination in housing and housing-related transactions on the basis of race, religion, or national origin (later expanded to include sex, familial status, and disability). This legislation was seen as a tribute to King's struggle in his final years to combat residential discrimination in the U.S. King's legacy in the United States and internationally continues to be that of a human rights icon.

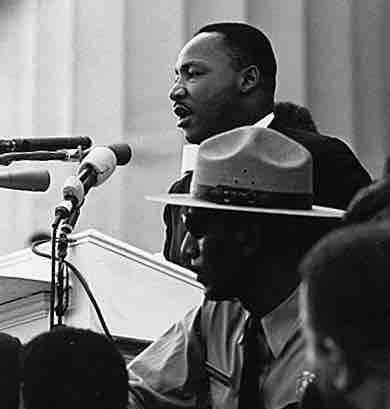

Martin Luther King, Jr. at the March on Washington

Dr. Martin Luther King giving his "I Have a Dream" speech during the March on Washington in Washington, D.C., on August 28, 1963.

INFLUENCES AND POLITICAL STANCES

As a Christian minister, King's main influence was the Christian gospels, which he would almost always quote in his religious meetings, speeches at church, and in public discourses. Veteran African-American civil rights activist Bayard Rustin was King's first regular advisor on nonviolence. King was also advised by the white activists Harris Wofford and Glenn Smiley. Rustin and Smiley came from the Christian pacifist tradition, and Wofford and Rustin both studied Gandhi's teachings. In 1959, King, inspired by Gandhi's success with non-violent activism, visited Gandhi's birthplace in India. This trip affected King in a profound way, deepening his understanding of non-violent resistance and reinforcing his commitment to America's struggle for civil rights.

As the leader of the SCLC, King maintained a policy of not publicly endorsing a U.S. political party or candidate. King did praise Democratic Senator Paul Douglas of Illinois as being the "greatest of all senators" because of his fierce advocacy for civil rights causes over the years but critiqued both parties' performance on promoting racial equality. He supported the ideals of democratic socialism, although he was reluctant to speak directly of this support due to the anti-communist sentiment being projected throughout America at the time, and the association of socialism with communism. King believed that capitalism could not adequately provide the basic necessities of many American people, particularly the African American community.

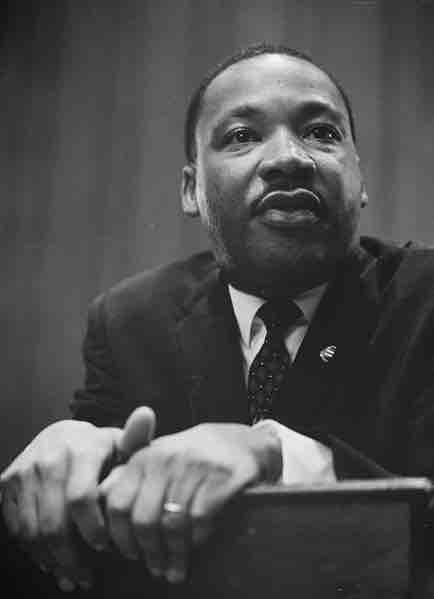

Dr. Martin Luther King (1964)

King giving a lecture on March 26, 1964.