Post-War Prosperity

The years immediately following World War II witnessed stability and prosperity for many Americans. Increasing numbers of workers enjoyed high wages, larger houses, better schools, more automobiles, and home comforts like vacuum cleaners and washing machines, which were made for labor-saving and to make housework easier. Inventions familiar in the early 21st century made their first appearance during this era.

The U.S. economy grew dramatically in the post-war period, expanding at a rate of 3.5% per annum between 1945 and 1970. During this period, many incomes doubled in a generation; a phenomenon that economist Frank Levy described as "upward mobility on a rocket ship." The substantial increase in average family income within a generation resulted in millions of office and factory workers being lifted into a growing middle class, enabling them to sustain a standard of living once considered reserved for the wealthy. As noted by Deone Zell, assembly line work paid well, while unionized factory jobs served as "stepping-stones to the middle class." By the end of the 1950s, 87% of all U.S. families owned at least one television, 75% owned automobiles, and 60% owned homes. By 1960, blue-collar workers had become the most prolific buyers of many luxury goods and services. Additionally, by the early 1970s, post-World War II U.S. consumers enjoyed higher levels of disposable income than those in any other country.

Economic Growth

The post-war years were also noted for the rise of the automotive and aviation industries. Many wartime industries continued to conduct business following World War II, driving innovation in newer industries such as aerospace and manufacturing. As companies grew in size, jobs, factory production, and consumer spending rose with it. Between 1946 and 1960, the United States saw greatly increased consumption of goods and services. Gross national product rose by 36% and personal consumption expenditures by 42%, with cumulative gains reflected in the incomes of families and unrelated individuals. While the number of these family units rose sharply from 43.3 million to 56.1 million in 1960, a rise of almost 23%, their average incomes grew even faster, from 3,940 in 1946 to 6,900 in 1960; a 43% increase. After taking inflation into account, the real advance was 16%.

More than 21 million housing units were constructed between 1946 and 1960, and in the latter year, 52% of consumer units in metropolitan areas were homeowners. In 1957, out of all the wired homes throughout the country, 96% had a refrigerator, 87% an electric clothes washer, 81% a television, 67% a vacuum cleaner, 18% a freezer, 12% an electric or gas clothes dryer, and 8% air conditioning. Automobile ownership also soared, with 72% of consumer units owning an automobile by 1960.

The period from 1946 to 1960 also saw a substantial increase in paid leisure time of working people. The 40-hour workweek established by the Fair Labor Standards Act in covered industries became the actual schedule in most workplaces by 1960. The majority of workers also enjoyed paid vacations and industries catering to leisure activities blossomed.

Educational outlays were also greater than in other countries, while a higher proportion of young people graduated from high schools and universities compared with elsewhere in the world, as hundreds of new colleges and universities opened every year. At the advanced level, U.S. science, engineering, and medicine were world-renowned.

In regard to social welfare, the post-war era saw a considerable improvement in insurance for workers and their dependents against the risks of illness, as private insurance programs like Blue Cross and Blue Shield expanded. With the notable exception of farm and domestic workers, Social Security covered virtually all members of the labor force. In 1959, about two-thirds of factory workers and three-fourths of office workers were provided with supplemental private pension plans.

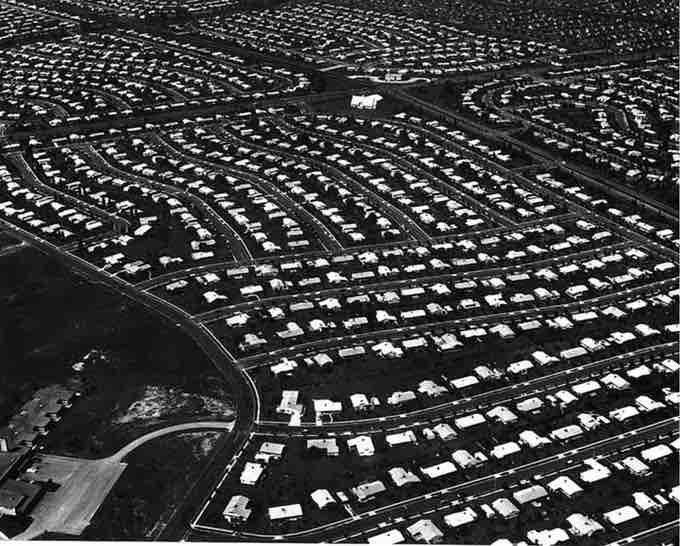

Many city dwellers gave up cramped apartments for a suburban lifestyle centered on children and housewives, with the male breadwinner commuting to work. Suburbia encompassed a third of the nation's population by 1960. Suburban growth was not only a result of post-war prosperity, but innovations of the single-family housing market with low interest rates on 20- and 30-year mortgages and low down payments, especially for veterans. William Levitt began a national trend with his use of mass-production techniques to construct a large Levittown housing development on Long Island, NY. Meanwhile, the suburban population swelled because of the baby boom, which was a dramatic increase in fertility in the period of 1942–1957.

Corporatization

The rapid social and technological changes brought a growing corporatization of the United States and the decline of smaller businesses, which often suffered from high post-war inflation and mounting operating costs. Newspapers declined in numbers and consolidated. The railroad industry, once one of the cornerstones of the U.S. economy and an immense and often scorned influence on national politics, also suffered from explosive automobile sales and the construction of the interstate system. By the end of the 1950s, it was well into decline and by the 1970s became completely bankrupt, necessitating a federal government takeover. Smaller automobile manufacturers such as Nash, Studebaker, and Packard were unable to compete with the so-called Big Three (General Motors, Ford, and Chrysler) in the new post-war world and gradually declined into oblivion. Suburbanization caused the gradual movement of working-class people and jobs out of the inner cities as shopping centers displaced the traditional downtown stores. In time, this would have disastrous effects on urban areas.

The Excluded

The new prosperity did not extend to everyone. Many Americans continued to live in poverty throughout the 1950s, especially older people and African Americans, the latter of whom continued to earn far less than their white counterparts on average in the two decades following the end of World War II. Immediately after the war, 12 million returning veterans were in need of work and in many cases could not find it. In addition, labor strikes rocked the nation; in some cases exacerbated by racial tensions due to African-Americans having taken jobs during the war and now being faced with irate returning veterans who demanded that they step aside. The huge number of women employed in the workforce in the war were also rapidly cleared out to make room for men.

Between one-fifth and one-fourth of the population could not survive on the income they earned. The older generation of Americans did not benefit as much from the post-war economic boom, especially as many had never recovered financially from the loss of their savings during the Great Depression. Many blue-collar workers continued to live in poverty, with 30% of those employed in industry. Racial differences were staggering. In 1947, 60% of black families lived below the poverty level (defined in one study as below $3,000 in 1968), compared with 23% of white families. In 1968, 23% of black families lived below the poverty level, compared with 9% of white families.

Suburbia

Aerial view of Levittown, Pennsylvania, circa 1959.