Slaves During the Revolutionary War

During the American Revolutionary War, both the British and American governments, in principle, offered freedom and resettlement to slaves willing to fight for them. Free black people in the North and South fought on both sides of the Revolution, though most fought for the colonial rebels. Many African-American slaves became politically active during these years in support of the King, as they thought Great Britain might abolish slavery in the colonies at the end of the conflict. Tens of thousands used the turmoil of war to escape from slavery.

White American advocates of independence were commonly called out in Britain for their hypocritical calls for freedom while maintaining slavery in the colonies. Despite their criticism, however, the British continued to permit the slave trade in other parts of the world.

Slavery in the New Constitution

Representation and the Three-Fifths Compromise

One of the most contentious slavery-related questions during the drafting of the Constitution was whether slaves would be counted as part of the population in determining representation in the Congress, or if they would be considered property not entitled to representation. Delegates from states with large populations of slaves argued that slaves should be considered people in determining representation. Simultaneously, they argued slaves should be considered property if the new government were to levy taxes on the states based on population. Delegates from states where slavery had become rare argued the opposite: that slaves should be included in taxation, but not in determining representation.

Finally, delegates James Wilson and Robert Sherman proposed the Three-Fifths Compromise, which the convention eventually adopted. This final compromise established the policy of counting slaves as three-fifths of a person. This reduced the slave states' power relative to the original Southern proposals, but increased it over the Northern proposal.

Slave Trade

Another issue was what should be done about the international slave trade and slave importation. While slavery was a debated issue, it also bolstered the economic backbone of the United States. The agricultural economy of the US South especially depended on slavery and the internal slave trade to provide free labor. If the Constitution adopted a plan that upset one region, then the states of that region may have withdrawn from the Philadelphia Convention. Convention delegates agreed to incorporate provisions supporting and protecting slavery in the Constitution to placate slaveholding states that refused to join the Union if slavery were not allowed.

To address this, Section 9 of Article I of the Constitution allowed continued importation of slaves. By for two decades prohibiting changes to the regulation of the slave trade, Article V effectively protected the trade until 1808. During that time, planters in states of the lower South imported tens of thousands of slaves. As further protection for slavery, the delegates approved Section 2 of Article IV, which prohibited citizens from providing assistance to escaping slaves, and required the return of chattel property to owners.

Jefferson and Slavery

Though Thomas Jefferson, a slaveholder, wrote the Declaration of Independence, the document propounded ideals of freedom that became important to the abolitionist movement. Jefferson, a political advocate of liberty and equality among men, lived in a slave society; he owned plantations spanning thousands of acres, and inherited hundreds of slaves during his lifetime. As a slaveholder, Jefferson perpetuated the slave society in which he lived, while also making contributions to the rise of anti-slavery constitutionalism in the United States.

Jefferson's personal views on race were complicated and ambivalent. He took actions that both advanced and limited slavery in the United States. In 1778, with Jefferson's leadership, the Virginia General Assembly banned importation of slaves into Virginia, making it one of the first jurisdictions in the world to ban the slave trade. Some historians have claimed that, as a representative to the Continental Congress, Thomas Jefferson wrote an amendment or bill that would abolish slavery. However, it has been documented that he refused to add gradual emancipation, stating that the timing was not right. After 1785, Jefferson remained publicly silent on, or did little to change, slavery within the United States.

Slavery from 1776 to 1804

Between 1776 and 1804, slavery was outlawed in every state north of the Ohio River and the Mason–Dixon Line. Starting in 1777, Northern states started to abolish slavery, beginning with Vermont, which ended the practice under its new state constitution. Massachusetts effectively ended slavery before the end of the century by means of a court case. States usually instituted abolition on a gradual schedule, with no government compensation to the owners. Many states, such as New York, New Jersey, and Connecticut, required long apprenticeships of former slave children before they gained freedom and came of age as adults.

Through the Northwest Ordinance of 1787, slavery was prohibited in the territories northwest of the Ohio River, while territories south of it (and Missouri) did allow slavery. In the first two decades after the war, the legislatures of the slave states Virginia, Maryland, and Delaware made it easier for slaveholders to free their slaves. Numerous slaveholders in the Upper South took advantage of the changes: the proportion of free blacks went from less than 1% before the war to more than 10% overall by 1810. After this time, few slaves were freed in the South except those who were personal favorites or the master's children.

The demand for slaves in the South rose with the growth of cotton as a commodity crop, especially after the invention of the cotton gin, which enabled widespread cultivation of short-staple cotton in the upland regions. As the demand for slave labor in the Upper South decreased because of changes in crops, planters began selling their slaves to traders and markets to the Deep South in an internal slave trade. This caused the forced migration of an estimated one million slaves during the following decades.

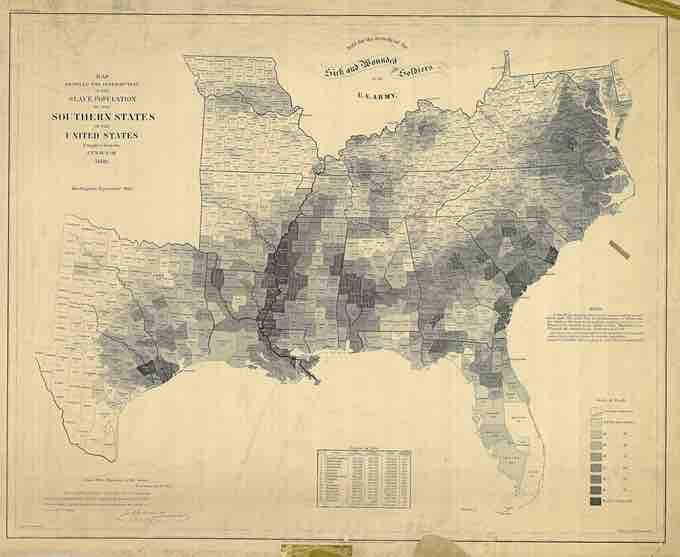

Map showing the distribution of the slave population of the US Southern states.

The map, compiled from the Census of 1860, was sold for the benefit of sick and wounded soldiers of the US Army.