Separation of Church and State

The modern concept of a wholly secular government is sometimes attributed to English philosopher John Locke. However, the phrase "separation of church and state" in this context is generally traced to a January 1, 1802, letter by Thomas Jefferson, addressed to the Danbury Baptist Association in Connecticut and published in a Massachusetts newspaper. Echoing the language of the founder of the first Baptist church in America, Roger Williams—who had written in 1644 of a "hedge or wall of separation between the garden of the church and the wilderness of the world"—Jefferson wrote, "I contemplate with sovereign reverence that act of the whole American people which declared that their legislature should 'make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,' thus building a wall of separation between Church & State."

Thomas Jefferson, Founding Father and Third President of the United States

Thomas Jefferson used the phrase "a wall of separation between Church and State" when he described the First Amendment's restriction on the legislative branch of the federal government.

Early History

Many early immigrant groups traveled to America to worship freely, particularly after the English Civil War and religious conflict in France and Germany. These immigrants included nonconformists, such as the Puritans, as well as Catholics. Despite a common background, the groups' views on religious tolerance varied. While some prominent individuals, such as Roger Williams who founded Rhode Island, and William Penn who founded the Province of Pennsylvania, ensured protection of religious minorities within their colonies, colonies such as Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay had established churches. The Dutch colony of New Netherland established the Dutch Reformed Church and outlawed all other worship, though enforcement was uncommon. Religious conformity was desired partly for financial reasons, as the established church was responsible for poverty relief, putting dissenting churches at a significant disadvantage.

Colonial Support for Separation

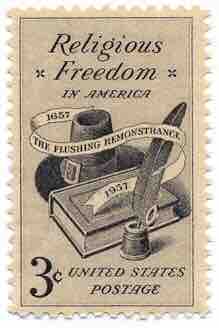

The Flushing Remonstrance was a petition for religious freedom circulated in the colonies in 1657, and is considered a precursor to the Constitution's provision on the separation of church and state. The document was signed December 27, 1657 by a group of English citizens in America who were offended by persecution of Quakers and the religious policies of Governor of New Netherland Peter Stuyvesant. Stuyvesant had formally banned all religions other than that of the Dutch Reformed Church from being practiced in the colony, in accordance with the laws of the Dutch Republic. The signers indicated their "desire therefore in this case not to judge lest we be judged, neither to condemn least we be condemned, but rather let every man stand or fall to his own Master."

Kenneth T. Jackson, president of the New York Historical Society and professor of history at Columbia University, described the Flushing Remonstrance as "the first thing that we have in writing in the United States where a group of citizens attests on paper and over their signature the right of the people to follow their own conscience with regard to God—and the inability of government, or the illegality of government, to interfere with that. "

Given the wide diversity of opinions on Christian theological matters in the newly independent United States, the Constitutional Convention believed government-sanctioned religion would disrupt, rather than bind, the newly formed union. Some opposed support of any established church at the state level; for instance, Thomas Jefferson's influential Statute for Religious Freedom was enacted in 1786 to ensure religious freedom in Virginia.

Establishment Clause

The Establishment Clause is the first of several pronouncements in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. It was created mainly as a consensus among all the religious groups in America in 1787, to prevent one religion from having too much influence. It stated: "Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion." Together with the Free Exercise Clause ("... or prohibiting the free exercise thereof"), these two clauses comprise the "religion clauses" of the First Amendment, which is part of a group of the 10 initial constitutional amendments known as the Bill of Rights.

The establishment clause has generally been interpreted to prohibit: 1) Congress' establishment of a national religion, and 2) US governmental preference of one religion over another.

Origin of the Clause

After the new Constitution was written during the Philadelphia Convention of 1787, there was a great deal of tension and uncertainty over whether the states would ratify it. To ensure ratification by all states, supporters of the Constitution (Federalists) agreed to add a group of amendments that would serve as the Bill of Rights. Many against the Constitution (Anti-Federalists) refused to ratify unless such individual rights were protected. When the First Federal Congress met in 1789, James Madison implemented the idea by introducing 17 amendments. By December 1791, 10 were ratified by the necessary three-fourths of the states, and these became part of the US Constitution, and thereinafter known as the Bill of Rights.

The establishment clause arose as an important issue to address during Madison's efforts to ratify the Constitution. Virginia had disestablished the gentry-supported Church of England during and after the American Revolution, leaving the Baptists in a position of political influence. Colonel Thomas Barber, an opponent of the Constitution in Madison's home state of Virginia, began a campaign for election to the state's ratifying convention. He garnered support among the local Baptists by warning them that the Constitution had no safeguard against creating a new national church. To head off Barber's challenge, Madison met with influential Baptist preacher John Leland and promised that, in exchange for Leland's support of ratification, he would sponsor several amendments. These were ultimately combined into the First Amendment.

Flushing Remonstrance

A US postage stamp commemorating religious freedom and the Flushing Remonstrance, a petition for religious freedom circulated in American colonies in 1657 and considered a precursor to the Constitution's provision on the separation of church and state.