Introduction: The Missouri Compromise

Another stage of U.S. expansion took place when inhabitants of Missouri began petitioning for statehood beginning in 1817. The Missouri Compromise was an agreement passed in 1820 between the pro-slavery and antislavery factions in the U.S. Congress, involving primarily the regulation of slavery in the western territories. It prohibited slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north, except within the boundaries of the proposed state of Missouri. Prior to the agreement, the House of Representatives had refused to accept this compromise and a conference committee was appointed.

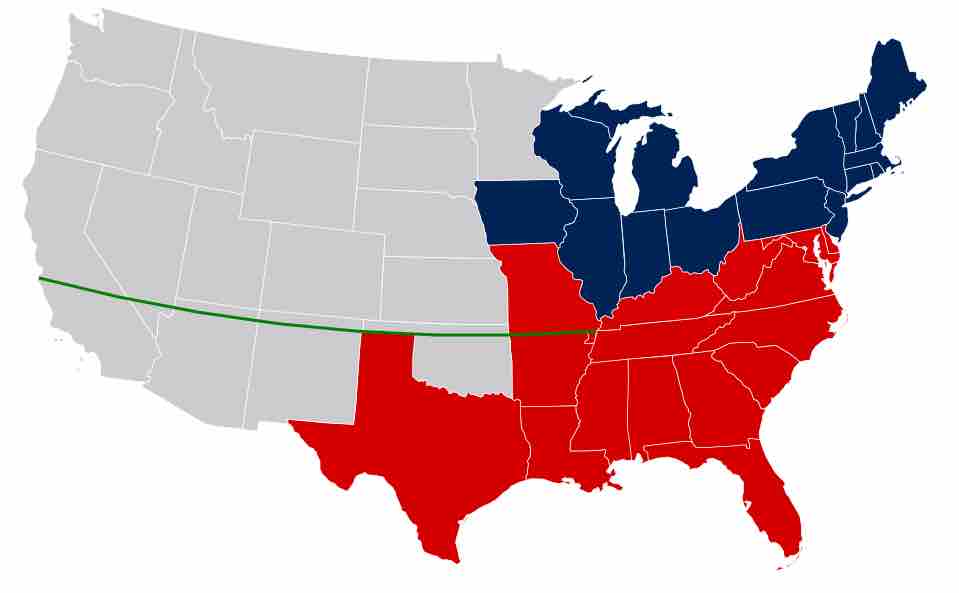

Missouri Compromise line

This map of the United States, circa 1820, shows the line between free and slave states that was established by the Missouri Compromise of 1820. The line extended along the parallel 36°30′ north, which roughly runs along the northern edge of present-day North Carolina, Tennessee, Arkansas, Oklahoma, New Mexico, Arizona, and westward through Nevada and California.

The Issue of Slavery

The Missouri territory had been part of the Louisiana Purchase and was the first part of that vast acquisition to apply for statehood. By 1818, tens of thousands of settlers had flocked to Missouri, including slaveholders who brought with them some ten thousand slaves. When the status of the Missouri territory was taken up in earnest in the U.S. House of Representatives in early 1819, the territory's admission to the Union proved to be no easy matter, because it brought to the surface a violent debate over whether slavery would be allowed in the new state.

Politicians had sought to avoid the issue of slavery ever since the 1787 Constitutional Convention arrived at an uneasy compromise in the form of the “three-fifths clause.” This provision stated that the entirety of a state’s free population and 60 percent of its enslaved population would be counted in establishing the number of that state’s members in the House of Representatives and the size of its federal tax bill. Although slavery existed in several northern states at the time, the compromise had angered many northern politicians because, they argued, the “extra” population of slaves would give southern states more votes than they deserved in both the House and the Electoral College. Admitting Missouri as a slave state also threatened the tenuous balance between free and slave states in the Senate by giving slave states a two-vote advantage.

The Tallmadge Amendment

In 1819, a bill was drafted to enable the people of the Missouri Territory to draft a constitution and form a government preliminary to admission into the Union, and the bill was brought before the House of Representatives on February 13. James Tallmadge of New York offered an amendment (named the "Tallmadge Amendment") that forbade further introduction of slaves into Missouri and mandated that all children of slave parents born in the state after its admission should be free at the age of 25. Debaters of the amendment were largely divided along sectional lines, rather than party lines. With only a few exceptions, northerners supported the Tallmadge Amendment regardless of party affiliation, and southerners opposed it despite having party differences on other matters. The House adopted the measure and incorporated it into the bill, which was passed on February 17, 1819. The Senate, however, refused to concur with the amendment, and the whole measure was lost. The crisis over Missouri led to strident calls for disunion and threats of civil war.

The Missouri Compromise

Congress finally came to an agreement called the "Missouri Compromise" in 1820. Missouri and Maine (which had been part of Massachusetts) would enter the Union at the same time: Maine as a free state and Missouri as a slave state. The balance between free and slave states was maintained in the Senate, and southerners did not have to fear that Missouri slaveholders would be deprived of their human property. To prevent similar conflicts each time a territory applied for statehood, a line coinciding with the southern border of Missouri (at latitude 36° 30') was drawn across the remainder of the Louisiana Territory. Slavery could exist south of this line but was forbidden north of it, with the obvious exception of Missouri.

Impact on Political Discourse

The debate leading up to the Compromise raised the issue of sectional balance. The country had been equally divided between eleven slave states and eleven free states. To admit Missouri as a slave state would tip the balance in the Senate (made up of two senators per state) in favor of the slave states. For this reason, northern states wanted Maine admitted as a free state to maintain the balance.

The Compromise of 1820 was an important example of Congressional exclusion of slavery from U.S. territories acquired since the Northwest Ordinance. Following Maine's 1820 and Missouri's 1821 admissions to the Union, no other states were admitted until 1836, when Arkansas was admitted as a slave state, followed by Michigan in 1837 as a free state.

Repeal

The provisions of the Missouri Compromise forbidding slavery in the former Louisiana Territory north of the parallel 36°30′ north were effectively repealed by the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854. This occurred despite efforts made to fight the Act by prominent speakers, including Abraham Lincoln in his "Peoria Speech."

In the Dred Scott v. Sandford case in 1857, the Supreme Court ruled that Congress did not have authority to prohibit slavery in territories and that those provisions of the Missouri Compromise were unconstitutional. Under the Admission Act of Missouri, it ruled that African Americans and mixed-race individuals did not qualify as citizens of the United States.