Election of 1856

The election of 1856 demonstrated the extremity of sectional polarization in national politics during this era. Since the previous election, the Whig Party had disintegrated over the issue of slavery, and new parties (including the Republican Party) competed to replace it. The Republicans nominated John C. Frémont, who condemned the Kansas-Nebraska Act and supported measures to curtail the expansion of slavery. The American Party (known as the Know-Nothing Party) nominated former president Millard Fillmore, who largely ignored the slave issue in favor of an anti-immigrant platform.

John C. Frémont

Republican candidate in the election of 1856.

The Democrats, on the other hand, supported James Buchanan. He had remained out of the crossfire of sectional disputes in his post as ambassador to Britain, making him appear more neutral and therefore appealing to a wider cross-section of Democrats than other potential nominees, such as incumbent President Franklin Pierce. Buchanan embraced the relatively moderate popular sovereignty approach to the expansion of slavery in his election platform and warned that the Republican Party was a coalition of radical antislavery extremists that would force the country into Civil War. Buchanan won the election of 1856 with the full support of the South as well as five free states.

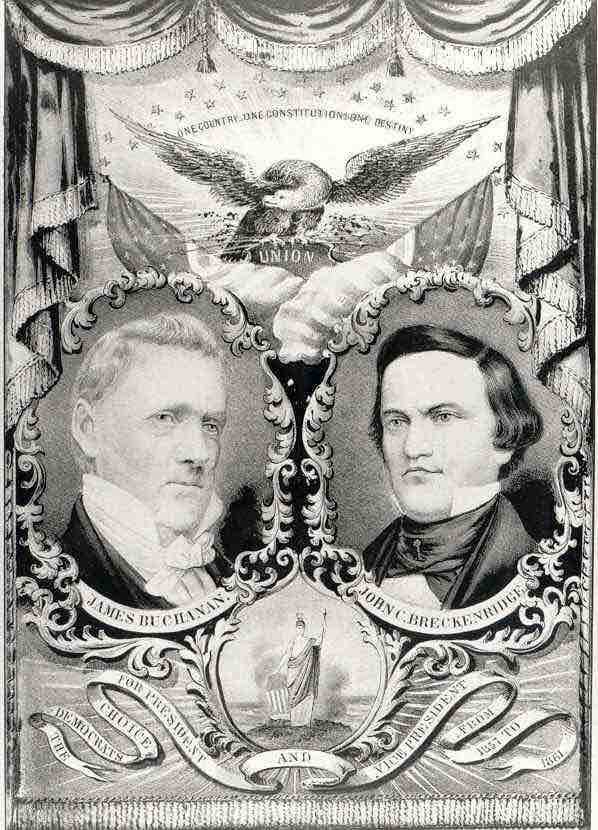

1856 Democratic Party campaign poster

A Buchanan/Breckenridge campaign poster.

Although Buchanan won the election and Frémont received fewer than 600 votes in all slave states, the results in the Electoral College indicated that the Republican Party could succeed in the next election if they won just two more states. Buchanan had won 45.3 percent of the popular vote and 174 electoral votes whereas Frémont had won 33.1 percent of the popular vote and 114 electoral votes. Fillmore won 21.6 percent of the popular vote and eight electoral votes.

James Buchanan

Democratic candidate for president in 1856 and fifteenth president of the United States.