In ancient philosophy, there was no difference between the liberal arts of mathematics and the study of history, poetry, or politics; only with the development of mathematical proofs did there gradually arise a perceived difference between scientific disciplines and the humanities or liberal arts. Thus, Aristotle studied planetary motion and poetry with the same methods, and Plato mixed geometrical proofs with his demonstration on the state of intrinsic knowledge.

However, by the end of the 17th century, a new scientific paradigm was emerging, particularly with the work of Isaac Newton in physics. Newton, by revolutionizing what was then called natural philosophy, changed the basic framework by which individuals understood what was scientific. While Newton was merely the archetype of an accelerating trend, his work highlights an important distinction. For Newton, mathematical truth was objective and absolute: it flowed from a reality independent of the observer and it worked by its own rules. Mathematics was the gold standard of knowledge. In the realm of other disciplines, this created a pressure to express ideas in the form of mathematical relationships, or laws. Such laws became the model that other disciplines would emulate.

In the late 19th century, scholars increasingly tried to apply mathematical laws to explain human behavior. Among the first efforts were the laws of philology, which attempted to map the change over time of sounds in a language. At first, scientists sought mathematical truth through logical proofs. But in the early 20th century, statistics and probability theory offered a new way to divine mathematical laws underlying all sorts of phenomena. As statistics and probability theory developed, they were applied to empirical sciences, such as biology, and to the social sciences. The first thinkers to attempt to combine scientific inquiry with the exploration of human relationships were Emile Durkheim in France and William James in the United States . Durkheim's sociological theories and James's work on experimental psychology had an enormous impact on those who followed.

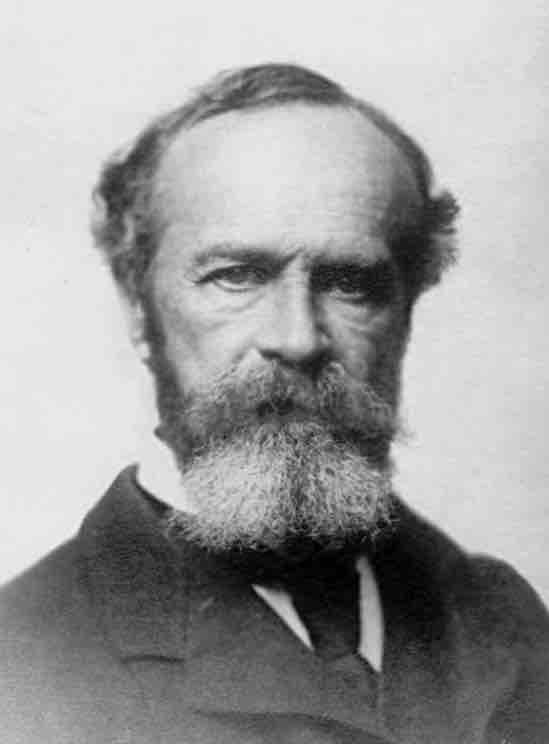

William James

William James was one of the first Americans to explore human relations scientifically.

Quantitative and Qualitative Methods

Sociology embodies several tensions, such as those between quantitative and qualitative methods, between positivist and interpretive orientations, and between objective and critical approaches. Positivist sociology (also known as empiricist) attempts to predict outcomes based on observed variables. Interpretive sociology attempts to understand a culture or phenomenon on its own terms.

Early sociological studies considered the field to be analogous to the natural sciences, like physics or biology. Many researchers argued that the methodology used in the natural sciences was perfectly suited for use in the social sciences. By employing the scientific method and emphasizing empiricism, sociology established itself as an empirical science and distinguished itself from other disciplines that tried to explain the human condition, such as theology, philosophy, or metaphysics.

Early sociologists hoped to use the scientific method to explain and predict human behavior, just as natural scientists used it to explain and predict natural phenomena. Still today, sociologists often are interested in predicting outcomes given knowledge of the variables and relationships involved. This approach to doing science is often termed positivism or empiricism. The positivist approach to social science seeks to explain and predict social phenomena, often employing a quantitative approach.

Understanding Culture and Behavior Instead of Predicting

But human society soon showed itself to be less predictable than the natural world. Scientists like Wilhelm Dilthey and Heinrich Rickert began to catalog ways in which the social world differs from the natural world. For example, human society has culture, unlike the societies of most other animals, which are based on instincts and genetic instructions that are passed between generations biologically, not through social processes. As a result, some sociologists proposed a new goal for sociology: not predicting human behavior, but understanding it. Max Weber and Wilhelm Dilthey introduced the concept of verstehen, or understanding. The goal of verstehen is less to predict behavior than it is to understand behavior. It aims to understand a culture or phenomenon on its own terms rather than trying to develop a theory that allows for prediction.

Sociology's inability to perfectly predict the behavior of humans has led some to label it a "soft science. " While some might consider this label derogatory, in a sense it can be seen as an admission of the remarkable complexity of humans as social animals. And, while arriving at a verstehen-like understanding of a culture adopts a more subjective approach, it nevertheless employs systematic methodologies like the scientific method. Both positivist and verstehen approaches employ a scientific method as they make observations and gather data, propose hypotheses, and test their hypotheses in the formulation of theories.